<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Stanisław Marcin Ulam, 1909

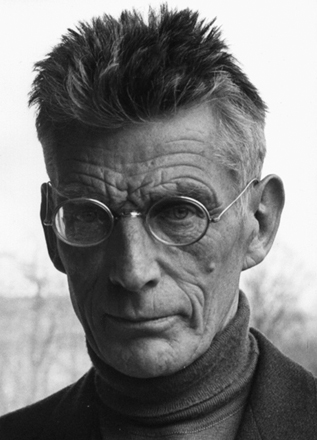

- Writer and Playwright Samuel Barclay Beckett, 1906

- Third President of the United States Thomas Jefferson, 1743

Samuel Barclay Beckett (13 April 1906 – 22 December 1989) was an Irish avant-garde writer, dramatist and poet, writing in English and French. Beckett's work offers a bleak outlook on human culture and both formally and philosophically became increasingly minimalist.

As a student, assistant, and friend of James Joyce, Beckett is considered one of the last modernists; as an inspiration to many later writers, he is sometimes considered one of the first postmodernists. He is also considered one of the key writers in what Martin Esslin called "Theatre of the Absurd." As such, he is widely regarded as one of the most influential writers of the 20th century. Beckett was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1969 for his "writing, which—in new forms for the novel and drama—in the destitution of modern man acquires its elevation". Beckett was elected Saoi of Aosdána in 1984. He died in Paris of respiratory problems. The Beckett family (originally Becquet) were rumoured to be of Huguenot stock and to have moved to Ireland from France after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes of 1598. The Becketts were members of the Church of Ireland. The family home, Cooldrinagh in the Dublin suburb of Foxrock,

was a large house and garden complete with tennis court built in 1903

by Samuel's father William. The house and garden, together with the

surrounding countryside where he often went walking with his father,

the nearby Leopardstown Racecourse, the Foxrock railway station and

Harcourt Street station at the city terminus of the line, all feature

in his prose and plays. Beckett's father was a quantity surveyor and his mother a nurse. Samuel

Beckett was born on Good Friday, April 13, 1906 to William Frank

Beckett, a 35 year old Civil Engineer, and May Barclay (also 35 at

Beckett's birth), whom Beckett had married in 1901. Beckett had one

older brother, Frank Edward Beckett (born 1902). At the age of five,

Beckett attended a local playschool, where he started to learn music,

and then moved to Earlsford House School in the city centre near

Harcourt Street. In 1919, Beckett went to Portora Royal School in Enniskillen, County Fermanagh—the school Oscar Wilde attended. A natural athlete, Beckett excelled at cricket as a left-handed batsman and a left-arm medium-pacebowler. Later, he was to play for Dublin University and played two first-class games against Northamptonshire. As a result, he became the only Nobel laureate to have an entry in Wisden Cricketers' Almanack, the "bible" of cricket. Beckett studied French, Italian, and English at Trinity College, Dublin from 1923 to 1927. While at Trinity, one of his tutors was the eminent Berkeley scholar and Berkelian Dr. A. A. Luce. Beckett graduated with a B.A., and—after teaching briefly at Campbell College in Belfast—took up the post of lecteur d'anglais in the École Normale Supérieure in Paris. While there, he was introduced to renowned Irish author James Joyce by Thomas MacGreevy,

a poet and close confidant of Beckett who also worked there. This

meeting was soon to have a profound effect on the young man, and

Beckett assisted Joyce in various ways, most particularly by helping

him research the book that would eventually become Finnegans Wake. In

1929, Beckett published his first work, a critical essay entitled

"Dante...Bruno. Vico..Joyce". The essay defends Joyce's work and

method, chiefly from allegations of wanton obscurity and dimness, and

was Beckett's contribution to Our Exagmination Round His Factification for Incamination of Work in Progress, a book of essays on Joyce which also included contributions by Eugene Jolas, Robert McAlmon, and William Carlos Williams,

among others. Beckett's close relationship with Joyce and his family,

however, cooled when he rejected the advances of Joyce's daughter Lucia owing to her progressing schizophrenia. It was also during this period that Beckett's first short story, "Assumption", was published in Jolas's periodical transition. The next year he won a small literary prize with his hastily composed poem "Whoroscope", which draws from a biography of René Descartes that Beckett happened to be reading when he was encouraged to submit. In

1930, Beckett returned to Trinity College as a lecturer. He soon became

disillusioned with his chosen academic vocation, however. He expressed

his aversion by playing a trick on the Modern Language Society of

Dublin, reading a learned paper in French on a Toulouse author

named Jean du Chas, founder of a movement called Concentrism; Chas and

Concentrism, however, were pure fiction, having been invented by

Beckett to mock pedantry. Beckett

resigned from Trinity at the end of 1931, terminating his brief

academic career. He commemorated this turning point in his life by

composing the poem "Gnome", inspired by his reading of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship and eventually published in the Dublin Magazine in 1934: After leaving Trinity, Beckett began to travel in Europe. He also spent some time in London, where in 1931 he published Proust, his critical study of French author Marcel Proust. Two years later, in the wake of his father's death, he began two years' treatment with Tavistock Clinic psychoanalyst, Dr. Wilfred Bion, who took him to hear Carl Jung's

third Tavistock lecture, an event which Beckett would still recall many

years later. The lecture focused on the subject of the "never properly

born," and aspects of it would become evident in Beckett's later works

including Watt and Waiting for Godot. In 1932, he wrote his first novel, Dream of Fair to Middling Women,

but after many rejections from publishers decided to abandon it; the

book would eventually be published in 1993. Despite his inability to

get it published, however, the novel did serve as a source for many of

Beckett's early poems, as well as for his first full-length book, the

1933 short-story collection More Pricks Than Kicks. Beckett also published a number of essays and reviews around the time, including "Recent Irish Poetry" (in The Bookman, August 1934) and "Humanistic Quietism", a review of his friend Thomas MacGreevy's Poems (in The Dublin Magazine, July–September 1934). These two reviews focused on the work of MacGreevy, Brian Coffey, Denis Devlin and Blanaid Salkeld, despite their slender achievements at the time, comparing them favourably with their Celtic Revival contemporaries and invoking Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot and the French symbolists as their precursors. In describing these poets as forming 'the nucleus of a living poetic in Ireland', Beckett was tracing the outlines of an Irish poetic modernist canon. In 1935 — the year that Beckett successfully published a book of his poetry, Echo's Bones and Other Precipitates —, he was also working on his novel Murphy. In May of that year, he wrote to MacGreevy that he had been reading about film and wished to go to Moscow to study with Sergei Eisenstein at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography in Moscow. In mid-1936, he wrote to Sergei Eisenstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin,

offering to become their apprentices. Nothing came of this, however, as

Beckett's letter was lost owing to Eisenstein's quarantine during the

smallpox outbreak, as well as his focus on a script re-write of his

postponed film production. Beckett, meanwhile, finished Murphy,

and then, in 1936, departed for extensive travel around Germany, during

which time he filled several notebooks with lists of noteworthy artwork

that he had seen, also noting his distaste for the Nazi savagery which was then overtaking the country. Returning to Ireland briefly in 1937, he oversaw the publishing of Murphy (1938),

which he himself translated into French the next year. He also had a

falling-out with his mother, which contributed to his decision to

settle permanently in Paris (where he would return for good following

the outbreak of World War II in 1939, preferring — in his own words — "France at war to Ireland at peace"). His was soon a known face in and around Left Bank cafés, where he strengthened his allegiance with Joyce and forged new ones with artists like Alberto Giacometti and Marcel Duchamp, with whom he regularly played chess. Sometime around December 1937, Beckett had a brief affair with Peggy Guggenheim, who nicknamed him "Oblomov" after the titular figure in Ivan Goncharov's novel. In Paris, in January 1938, while refusing the solicitations of a notorious pimp who

ironically went by the name of Prudent, Beckett was stabbed in the

chest and nearly killed. James Joyce arranged a private room for the

injured Beckett at the hospital. The publicity surrounding the stabbing

attracted the attention of Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil,

who knew Beckett slightly from his first stay in Paris; this time,

however, the two would begin a lifelong companionship. At a preliminary

hearing, Beckett asked his attacker for the motive behind the stabbing,

and Prudent casually replied, "Je ne sais pas, Monsieur. Je m'excuse" ("I do not know, sir. I'm sorry"). Beckett

occasionally recounted the incident in jest, and eventually dropped the

charges against his attacker — partially to avoid further formalities,

but also because he found Prudent to be personally likeable and

well-mannered. Beckett joined the French Resistance after

the 1940 occupation by Germany, working as a courier, and on several

occasions over the next two years was nearly caught by the Gestapo. In August 1942, his unit was betrayed and he and Suzanne fled south on foot to the safety of the small village of Roussillon, in the Vaucluse département in the Provence Alpes Cote d'Azur region.

Here he continued to assist the Resistance by storing armaments in the

back yard of his home. During the two years that Beckett stayed in

Roussillon he indirectly helped the Maquis sabotage the German army in the Vaucluse mountains, though he rarely spoke about his wartime work. Beckett was awarded the Croix de guerre and the Médaille de la Résistance by

the French government for his efforts in fighting the German

occupation; to the end of his life, however, Beckett would refer to his

work with the French Resistance as 'boy scoutstuff'. '[I]n order to keep in touch', he continued work on the novel Watt (begun in 1941 and completed in 1945, but not published until 1953) while in hiding in Roussillon. In

1945, Beckett returned to Dublin for a brief visit. During his stay, he

had a revelation in his mother’s room in which his entire future

literary direction appeared to him. This experience was later

fictionalized in the 1958 play Krapp's Last Tape. In the play, Krapp’s revelation, perhaps set on the East Pier in Dún Laoghaire during

a

stormy night, some critics have identified Beckett with Krapp to

the point of presuming Beckett's own artistic epiphany was at the same

location, in the same weather. Throughout the play, Krapp is listening

to a tape he made

earlier in his life; at one point he hears his younger self saying

this: “...clear to me at last that the dark I have always struggled to

keep under is in reality my most...” Krapp fast-forwards the tape

before the audience can hear the complete revelation. Beckett later

revealed to James Knowlson (which Knowlson relates in the biography Damned to Fame)

that the missing words on the tape are "precious ally". Beckett claimed

he was faced with the possibility of being eternally in the shadow of

Joyce, certain to never best him at his own game. Then he had a

revelation, as Knowlson says, which “has rightly been regarded as a

pivotal moment in his entire career." Knowlson goes on to explain the

revelation as told to him by Beckett himself: "In speaking of his own

revelation, Beckett tended to focus on the recognition of his own

stupidity ... and on his concern with impotence and ignorance. He

reformulated this for me, while attempting to define his debt to James

Joyce: 'I realized that Joyce had gone as far as one could in the

direction of knowing more, [being] in control of one’s material. He was

always adding to it; you only have to look at his proofs to see that. I

realized that my own way was in impoverishment, in lack of knowledge

and in taking away, in subtracting rather than in adding.'" Knowlson

explains: "Beckett was rejecting the Joycean principle that knowing

more was a way of creatively understanding the world and controlling it

... In future, his work would focus on poverty, failure, exile and loss

-- as he put it, on man as a 'non-knower' and as a 'non-can-er.'" In 1946, Jean-Paul Sartre’s magazine Les Temps Modernes published the first part of Beckett’s short story "Suite" (later to be called "La fin", or "The End"), not realizing that Beckett had only submitted the first half of the story; Simone de Beauvoir refused to publish the second part. Beckett also began to write his fourth novel, Mercier et Camier, which was not to be published until 1970. The novel, in many ways, presaged his most famous work, the play Waiting for Godot,

written not long afterwards, but more importantly, it was Beckett’s

first long work to be written directly in French, the language of most

of his subsequent works, including the poioumenon, a "trilogy" of novels he was soon to write: Molloy, Malone Dies and The Unnamable.

Despite being a native English speaker, Beckett chose to write in

French because—as he himself claimed—in French it was easier for him to

write "without style." Beckett is publicly most famous for the play Waiting for Godot. In a much-quoted article, the critic Vivian Mercier wrote

that Beckett "has achieved a theoretical impossibility—a play in which

nothing happens, that yet keeps audiences glued to their seats. What's

more, since the second act is a subtly different reprise of the first,

he has written a play in which nothing happens, twice. Like most of his works after 1947, the play was first written in French with the title En attendant Godot. Beckett worked on the play between October 1948 and January 1949. He

published it in 1952, and premiered it in 1953. The English translation

appeared two years later. The play was a critical, popular, and

controversial success in Paris. It opened in London in 1955 to mainly

negative reviews, but the tide turned with positive reactions by Harold

Hobson in The Sunday Times and, later, Kenneth Tynan. In the United States, it flopped in Miami, and had a qualified success in New York City.

After this, the play became extremely popular, with highly successful

performances in the U.S. and Germany. It is still frequently performed

today. As noted, Beckett was now writing mainly in French. He translated all of his works into the English language himself, with the exception of Molloy, whose translation was collaborative with Patrick Bowles. The success of Waiting for Godot opened

up a career in theatre for its author. Beckett went on to write a

number of successful full-length plays, including 1957's Endgame, the aforementioned Krapp's Last Tape (written in English), 1960's Happy Days (also written in English), and 1963's Play. In

1961, in recognition for his work, Beckett received the International

Publishers' Formentor Prize, which he shared that year with Jorge Luis Borges.

The

1960s were a period of change, both on a personal level and as a

writer. In 1961, in a secret civil ceremony in England, he married

Suzanne, mainly for reasons relating to French inheritance law. The

success of his plays led to invitations to attend rehearsals and

productions around the world, leading eventually to a new career as a

theatre director. In 1956, he had his first commission from the BBC Third Programme for a radio play, All That Fall.

He was to continue writing sporadically for radio, and ultimately for

film and television as well. He also started to write in English again,

though he continued to write in French until the end of his life. In October 1969, Beckett, on holiday in Tunis with Suzanne, learned he had won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Suzanne, who saw that her intensely private husband would be, from that

moment forth, saddled with fame, called the award a "catastrophe." While

Beckett did not devote much time to interviews, he would still

sometimes personally meet the artists, scholars, and admirers who

sought him out in the anonymous lobby of the Hotel PLM St. Jacques in

Paris near his Montparnasse home. Suzanne died on 17 July 1989. Suffering from emphysema and possibly Parkinson's disease and confined to a nursing home, Beckett died on 22 December of the same year. The two were interred together in the Cimetière Montparnasse in Paris, and share a simple granite gravestone which follows Beckett's directive that it be "any colour, so long as it's grey."