<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Henri Léon Lebesgue, 1875

- Painter Peter Paul Rubens, 1577

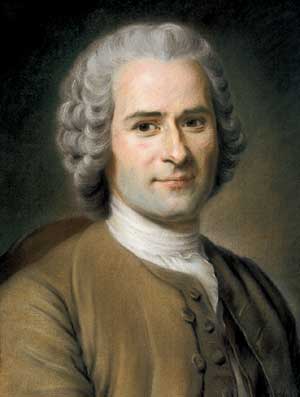

- Political Philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, 1712

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Geneva, 28 June 1712 – Ermenonville, 2 July 1778) was a major Genevois philosopher, writer, and composer of the 18th-century Enlightenment. His political philosophy influenced the French Revolution and the development of modern political and educational thought.

His novel, Emile: or, On Education, which he considered his most important work, is a seminal treatise on the education of the whole person for citizenship. His sentimental novel, Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse, was of great importance to the development of pre-Romanticism and romanticism in fiction. Rousseau's autobiographical writings: his Confessions, which initiated the modern autobiography, and his Reveries of a Solitary Walker were among the pre-eminent examples of the late 18th-century movement known as the "Age of Sensibility", featuring an increasing focus on subjectivity and introspection that has characterized the modern age. Rousseau

also wrote a play and two operas, and made important contributions to

music as a theorist. During the period of the French Revolution,

Rousseau was the most popular of the philosophes among members of the Jacobin Club. He was interred as a national hero in the Panthéon in Paris, in 1794, 16 years after his death Rousseau was born in 1712 in Geneva, which, since 1536, was a Huguenot republic and the seat of Calvinism (now part of Switzerland). Rousseau was proud that his family, of the moyen (or middle-class) order, had voting rights in that city and throughout his life he described himself as a citizen of

Geneva. In theory, Geneva was governed democratically by its male

voting citizens (who were a minority of the population). In fact, a

secretive executive committee, called the Little Council (made up of 25

members of its wealthiest families), ruled the city. In

1707 a patriot called Pierre Fatio protested at this situation, and the

Little Council had him shot. Jean-Jacques Rousseau's father Isaac was

not in the city at this time, but Jean-Jacques's grandfather supported

Fatio and was penalized for it. Rousseau's

father, Isaac Rousseau, was a watchmaker who, notwithstanding his

artisan status, was well educated and a lover of music. "A Genevan

watchmaker," Rousseau wrote, "is a man who can be introduced anywhere;

a Parisian watchmaker is only fit to talk about watches." Rousseau's mother, Suzanne Bernard Rousseau, the daughter of a Calvinist preacher, died of puerperal fever nine

days after his birth. He and his older brother François were

brought up by their father and a paternal aunt, also named Suzanne. Rousseau

had no recollection of learning to read, but he remembered how when he

was 5 or 6 his father encouraged his love of reading: Every

night, after supper, we read some part of a small collection of

romances [i.e., adventure stories], which had been my mother's. My

father's design was only to improve me in reading, and he thought these

entertaining works were calculated to give me a fondness for it; but we

soon found ourselves so interested in the adventures they contained,

that we alternately read whole nights together and could not bear to

give over until at the conclusion of a volume. Sometimes, in the

morning, on hearing the swallows at our window, my father, quite

ashamed of this weakness, would cry, "Come, come, let us go to bed; I

am more a child than thou art." Not long afterward, Rousseau abandoned his taste for escapist stories in favor of the antiquity of Plutarch's Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans, which he would read to his father while he made watches. When

Rousseau was 10, his father, an avid hunter, got into a legal quarrel

with a wealthy landowner on whose lands he had been caught trespassing.

To avoid certain defeat in the courts, he moved away to Nyon in the

territory of Bern, taking Rousseau's aunt Suzanne with him. He

remarried, and from that point Jean-Jacques saw little of him. Jean-Jacques

was left with his maternal uncle, who packed him, along with his own

son, Abraham Bernard, away to board for two years with a Calvinist

minister in a hamlet outside Geneva. Here the boys picked up the

elements of mathematics and drawing. Rousseau, who was always deeply

moved by religious services, for a time even dreamed of becoming a

Protestant minister. Virtually all our information about Rousseau's first youth has come from his posthumously published Confessions,

in which the chronology is somewhat confused, though recent scholars

have combed the archives for confirming evidence to fill in the blanks.

At age 13, Rousseau was apprenticed first to a notary and

then to an engraver who beat him. At 15, he ran away from Geneva (on 14

March 1728) after returning to the city and finding the city gates

locked due to the curfew. In adjoining Savoy he took shelter with a Roman Catholic priest, who introduced him to Françoise-Louise de Warens,

age 29. She was a noblewoman of Protestant background who was separated

from her husband. As professional lay proselytizer, she was paid by the

King of Piedmont to help bring Protestants to Catholicism. They sent the boy to Turin,

the capital of Savoy (which included Piedmont, in what is now Italy),

to complete his conversion. This resulted in his having to give up his

Genevan citizenship, although he would later revert to Calvinism in

order to regain it. In converting to Catholicism, both De Warens and

Rousseau were likely reacting to the severity of Calvinism's insistence

on the total depravity of

man. Leo Damrosch writes, "an eighteenth-century Genevan liturgy still

required believers to declare ‘that we are miserable sinners, born in

corruption, inclined to evil, incapable by ourselves of doing good'." De Warens, a deist by inclination, was attracted to Catholicism's doctrine of forgiveness of sins. Finding

himself on his own, since his father and uncle had more or less

disowned him, the teenage Rousseau supported himself for a time as a

servant, secretary, and tutor, wandering in Italy (Piedmont and Savoy)

and France. During this time, he lived on and off with De Warens, whom

he idolized and called his "maman". Flattered by his devotion,

De Warens tried to get him started in a profession, and arranged formal

music lessons for him. At one point, he briefly attended a seminary

with the idea of becoming a priest. When Rousseau reached 20, De Warens

took him as her lover, whilst intimate also with the steward of her

house. The sexual aspect of their relationship (in fact a ménage à trois)

confused Rousseau and made him uncomfortable, but he always considered

De Warens the greatest love of his life. A rather profligate spender,

she had a large library and loved to entertain and listen to music. She

and her circle, comprising educated members of the Catholic clergy,

introduced Rousseau to the world of letters and ideas. Rousseau had

been an indifferent student, but during his 20s, which were marked by

long bouts of hypochondria,

he applied himself in earnest to the study of philosophy, mathematics,

and music. At 25, he came into a small inheritance from his mother and

used a portion of it to repay De Warens for her financial support of

him. At 27, he took a job as a tutor in Lyon. In 1742, Rousseau moved to Paris in order to present the Académie des Sciences with a new system of numbered musical notation he believed would make his fortune. His system, intended to be compatible with typography, is based on a single line, displaying numbers representing intervals between

notes and dots and commas indicating rhythmic values. Believing the

system was impractical, the Academy rejected it, though they praised

his mastery of the subject, and urged him to try again. From

1743 to 1744, Rousseau had an honorable but ill-paying post as a

secretary to the Comte de Montaigue, the French ambassador to Venice. This awoke in him a lifelong love for Italian music, particularly opera. Rousseau's employer routinely received his stipend as much as a year late and paid his staff irregularly. After 11 months, Rousseau quit, taking from the experience a profound distrust of government bureaucracy. Returning to Paris, the penniless Rousseau befriended and became the lover of Thérèse Levasseur,

a pretty seamstress who was the sole support of her termagant mother

and numerous ne'er-do-well siblings. At first, they did not live

together, though later Rousseau took Thérèse and her

mother in to live with him as his servants, and himself assumed the

burden of supporting her large family. According to his Confessions,

before she moved in with him, Thérèse bore him a son and

as many as four other children (there is no independent verification

for this number).

Rousseau wrote that he persuaded Thérèse to give each of

the newborns up to a foundling hospital, for the sake of her "honor".

"Her mother, who feared the inconvenience of a brat, came to my aid,

and she [Thérèse] allowed herself to be overcome".

The foundling hospitals had been started as a reform to save the

numerous infants who were being abandoned in the streets of Paris.

Infant mortality at that date was extremely high — about 50 percent, in

large part because families sent their infants to be wet nursed. The

mortality rate in the foundling hospitals, which also sent the babies

out to be wet nursed, proved worse, however, and most of the infants

sent there likely perished. Ten years later, Rousseau made inquiries

about the fate of his son, but no record could be found. When Rousseau

subsequently became celebrated as a theorist of education and

child-rearing, his abandonment of his children was used by his critics,

including Voltaire and Edmund Burke, as the basis for ad hominem attacks.

In an irony of fate, Rousseau's later injunction to women to breastfeed

their own babies (as had previously been recommended by the French

natural scientist Buffon), probably saved the lives of thousands of infants. While in Paris, Rousseau became a close friend of French philosopher Diderot and, beginning with some articles on music in 1749, contributed numerous articles to Diderot and D'Alembert's great Encyclopédie, the most famous of which was an article on political economy written in 1755. Rousseau's

ideas were the result of an almost obsessive dialogue with writers of

the past, filtered in many cases through conversations with Diderot.

His genius lay in his strikingly original way of putting things rather

than in the originality, per se, of his thinking. In 1749, Rousseau was paying daily visits to Diderot, who had been thrown into the fortress of Vincennes under a lettre de cachet for opinions in his "Lettre sur les aveugles," that hinted at materialism, a belief in atoms, and natural selection. Rousseau had read about an essay competition sponsored by the Académie de Dijon to be published in the Mercure de France on

the theme of whether the development of the arts and sciences had been

morally beneficial. He wrote that while walking to Vincennes (about

three miles from Paris), he had a revelation that the arts and sciences

were responsible for the moral degeneration of mankind, who were

basically good by nature. According to Diderot, writing much later,

Rousseau had originally intended to answer this in the conventional

way, but his discussions with Diderot convinced him to propose the

paradoxical negative answer that catapulted him into the public eye.

Whatever the case, it was the great French naturalist Buffon who

had previously suggested that man's moral decline arose from his

acquisition of property and culture. Both Rousseau and Diderot would

have been aware of Buffon's speculations. Rousseau's 1750 "Discourse on the Arts and Sciences", in which he made that argument, was awarded the first prize and gained him significant fame. Rousseau continued his interest in music, and his opera Le Devin du Village (The Village Soothsayer) was performed for King Louis XV in

1752. The king was so pleased by the work that he offered Rousseau a

lifelong pension. To the exasperation of his friends, Rousseau turned

down the great honor, bringing him notoriety as "the man who had

refused a king's pension." He also turned down several other

advantageous offers, sometimes with a brusqueness bordering on

truculence that gave offense and caused him problems. The same year,

the visit of a troupe of Italian musicians to Paris, and their

performance of Giovanni Battista Pergolesi's La Serva Padrona, prompted the Querelle des Bouffons,

which pitted protagonists of French music against supporters of the

Italian style. Rousseau as noted above, was an enthusiastic supporter

of the Italians against Jean-Philippe Rameau and others, making an important contribution with his Letter on French Music. On returning to Geneva in 1754, Rousseau reconverted to Calvinism and regained his official Genevan citizenship. In 1755, Rousseau completed his second major work, the Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men (the Discourse on Inequality), which elaborated on the arguments of the Discourse on the Arts and Sciences. He also pursued an unconsummated romantic attachment with the 25-year-old Sophie d'Houdetot, which partly inspired his epistolary novel, Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse (also

based on memories of his idyllic youthful relationship with Mme de

Warens). Sophie was the cousin and house guest of Rousseau's patroness

and landlady Madame d'Epinay,

whom he treated rather highhandedly. He resented being at Mme

d'Epinay's beck and call and detested the insincere conversation and

shallow atheism of the Encyclopedistes whom

he met at her table. Wounded feelings gave rise to a bitter three-way

quarrel between Rousseau and Madame d'Epinay; her lover, the philologist Grimm;

and their mutual friend, Diderot, who took their side against Rousseau.

Diderot later described Rousseau as being, "false, vain as Satan,

ungrateful, cruel, hypocritical, and wicked ... He sucked ideas from

me, used them himself, and then affected to despise me". Rousseau's break with the Encyclopedistes coincided

with the composition of his three major works, in all of which he

emphasized his fervent belief in a spiritual origin of man's soul and

the universe, in contradistinction to the materialism of Diderot, La Mettrie, and d'Holbach. During this period Rousseau enjoyed the support and patronage of the Duc de Luxembourg, and the Prince de Conti,

two of the richest and most powerful nobles in France. These men truly

liked Rousseau and enjoyed his ability to converse on any subject, but

they also used him as a way of getting back at Louis XV and the political faction surrounding his mistress, Mme de Pompadour. Even with them, however, Rousseau went too far, courting rejection when he criticized the practice of tax farming, in which some of them engaged. Rousseau's 800-page novel of sentiment, Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse, was published in 1761 to

immense success. The book's rhapsodic descriptions of the natural

beauty of the Swiss countryside struck a chord in the public and may

have helped spark the subsequent nineteenth century craze for Alpine

scenery. In 1762, Rousseau published Du Contrat Social, Principes du droit politique (in English, literally Of the Social Contract, Principles of Political Right) in April and then Emile: or, On Education in May. The final section of Émile,

"The Profession of Faith of a Savoyard Vicar," was intended to be a

defense of religious belief. Rousseau's choice of a Catholic vicar of

humble peasant background (plausibly based on a kindly prelate he had

met as a teenager) as a spokesman for the defense of religion was in

itself a daring innovation for the time. The vicar's creed was that of Socinianism (or Unitarianism as it is called today). Because it rejected original sin and divine Revelation,

both Protestant and Catholic authorities took offense. Moreover,

Rousseau advocated the opinion that, insofar as they lead people to

virtue, all religions are equally worthy, and that people should

therefore conform to the religion in which they have been brought up.

This religious indifferentism caused

Rousseau and his books to be banned from France and Geneva. He was

condemned from the pulpit by the Archbishop of Paris, his books were

burned, and warrants were issued for his arrest. A sympathetic observer, British philosopher David Hume,

"professed no surprise when he learned that Rousseau's books were

banned in Geneva and elsewhere." Rousseau, he wrote, "has not had the

precaution to throw any veil over his sentiments; and, as he scorns to

dissemble his contempt for established opinions, he could not wonder

that all the zealots were in arms against him. The liberty of the press

is not so secured in any country … as not to render such an open attack

on popular prejudice somewhat dangerous.'" Rousseau,

who thought he had been defending religion, was crushed. Forced to flee

arrest he made his way, with the help of the Duc of Luxembourg and

Prince de Conti, to Neuchâtel, a Canton of the Swiss Confederation that was a protectorate of the Prussian crown.

His powerful protectors discreetly assisted him in his flight and they

helped to get his banned books (published in Holland) distributed in

France disguised as other works using false covers and title pages. In

the town of Môtiers, he sought and found protection under Lord Keith, who was the local representative of the free-thinking Frederick the Great of Prussia. While in Môtiers, Rousseau wrote the Constitutional Project for Corsica (Projet de Constitution pour la Corse, 1765). After

his house in Môtiers was stoned on the night of 6 September 1765,

Rousseau took refuge in Great Britain with Hume, who found lodgings for

him at a friend's country estate in Wootton in

Staffordshire. Neither Thérèse nor Rousseau was able to

learn English or make friends. Isolated, Rousseau, never emotionally

very stable, suffered a serious decline in his mental health and began

to experience paranoid fantasies about plots against him involving Hume

and others. “He is plainly mad, after having long been maddish”, Hume

wrote to a friend. Rousseau's

letter to Hume, in which he articulates the perceived misconduct,

sparked an exchange which was published in and received with great

interest in contemporary Paris. Although

officially barred from entering France before 1770, Rousseau returned

in 1767 under a false name. In 1768 he went through a marriage of sorts

to Thérèse (marriages between Catholics and Protestants

were illegal), whom he had always hitherto referred to as his

"housekeeper". Though she was illiterate, she had become a remarkably

good cook, a hobby her husband shared. In 1770 they were allowed to

return to Paris. As a condition of his return he was not allowed to

publish any books, but after completing his Confessions,

Rousseau began private readings in 1771. At the request of Madame

d'Epinay, who was anxious to protect her privacy, however, the police

ordered him to stop, and the Confessions was only partially published in 1782, four years after his death. All his subsequent works were to appear posthumously. In 1772, Rousseau was invited to present recommendations for a new constitution for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, resulting in the Considerations on the Government of Poland, which was to be his last major political work. In 1776, he completed Dialogues: Rousseau Judge of Jean-Jacques and began work on the Reveries of the Solitary Walker. In order to support himself, he returned to copying music, spending his leisure time in the study of botany. Although

a celebrity, Rousseau's mental health did not permit him to enjoy his

fame. His final years were largely spent in deliberate withdrawal.

However, he did respond favorably to an approach from the composer Gluck, whom he met in 1774. One of Rousseau's last pieces of writing was a critical yet enthusiastic analysis of Gluck's opera Alceste. While taking a morning walk on the estate of the marquis René Louis de Girardin at Ermenonville (28 miles northeast of Paris), Rousseau suffered a hemorrhage and died on 2 July 1778. He was 66. Rousseau

was initially buried at Ermenonville on the Ile des Peupliers, which

became a place of pilgrimage for his many admirers. Sixteen years after

his death, his remains were moved to the Panthéon in Paris in 1794, where they are located directly across from those of his contemporary, Voltaire. His tomb, in the shape of a rustic temple, on which, in bas relief an

arm reaches out, bearing the torch of liberty, evokes Rousseau's deep

love of nature and of classical antiquity. In 1834, the Genevan

government somewhat reluctantly erected a statue in his honor on the

tiny Île Rousseau in Lake Geneva. Today he is proudly claimed as their most celebrated native son. In 2002, the Espace Rousseau was established at 40 Grand-Rue, Geneva, Rousseau's birthplace.