<Back to Index>

- Botanist Carolus Clusius, 1526

- Painter Gabriele Münter, 1877

- 19th President of Mexico Álvaro Obregón Salido, 1880

PAGE SPONSOR

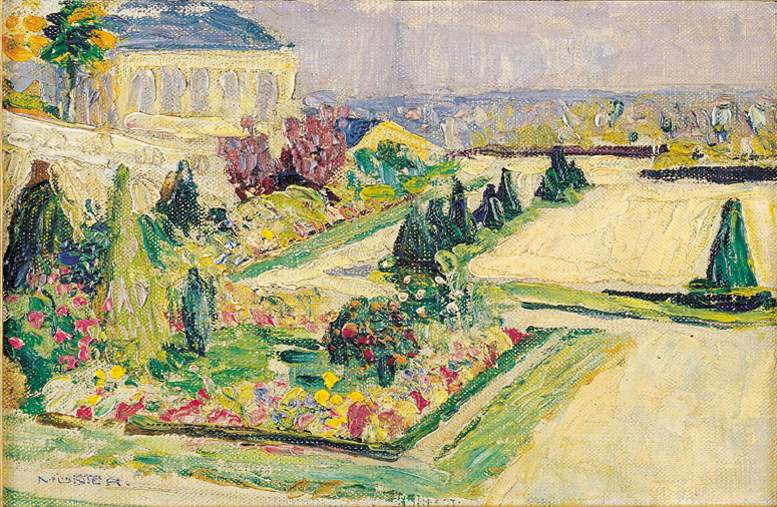

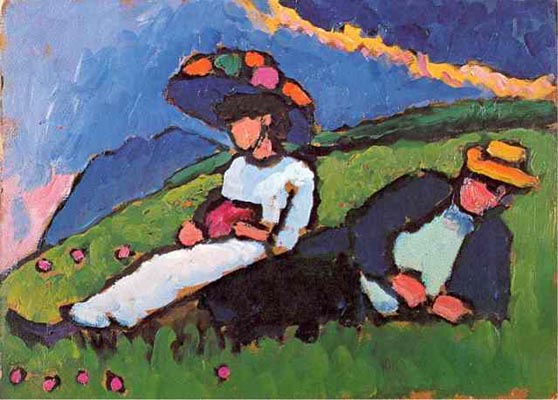

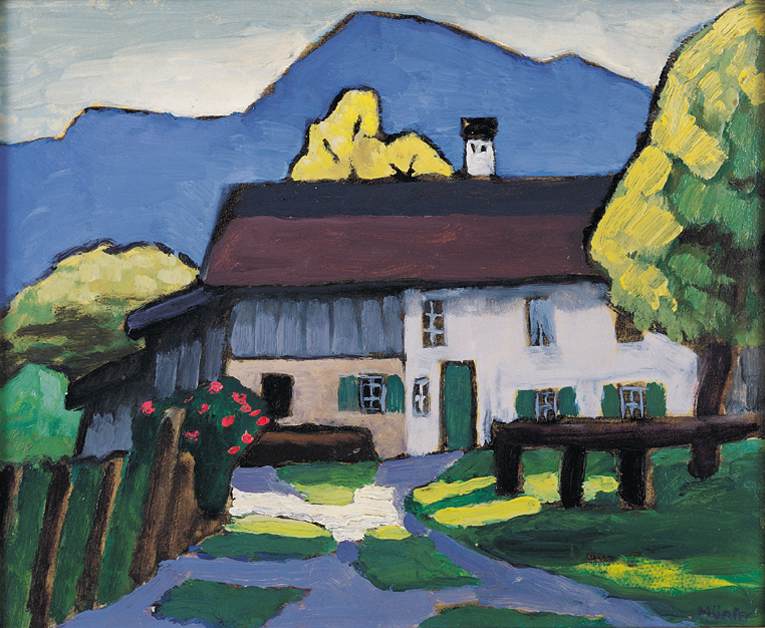

Gabriele Münter (19 February 1877 – 19 May 1962) was a German expressionist painter who was at the forefront of the Munich avant - garde in the early 20th century. Artists and writers associated with German Expressionism shared a rebellious attitude, which was influenced by the writings of Nietzsche, toward the materialism and mores of German imperial and bourgeois society. German Expressionistic art was an exegetic, and at times agonizing reaction against the ambiguities and formalism of pre-war radical art and its avant - garde mentality for a positive purpose that is to end the alienation of painting from society.

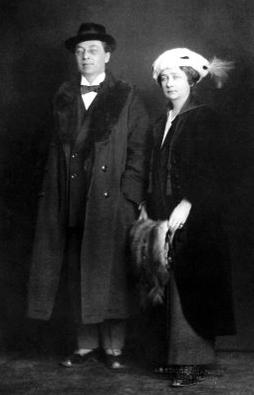

Gabriele Münter was born in Berlin and showed an interest in art from a young age. She received private tuition in drawing and attended the local Women Artists' School, as she was unable to enroll in the German art academies because she was female. Frustrated by her lack of respect as a female artist, Münter took to traveling as a means of gaining experience and finding herself as an artist. It was Münter's two year visit to the United States from 1898 - 1900 that ultimately solidified her desire to become an artist. For Münter, art was created to bring direction and order into her life, rescuing her from aimlessness, and granting her greater satisfaction and self confidence. It was Münter's travels that proved to have a tremendous impact on her work. Münter left Berlin to attend the progressive Phalanx School in Munich. There she studied sculpture, printmaking and painting and in 1902 began a very intimate and personal relationship with the School director Wassily Kandinsky; they were later engaged to be married. By 1907, Münter qualified as a working artist, along with 800 other painters and sculptors of the female sex.

"At first I experienced great difficulty with my brushwork - I mean with what the French call la touche de pinceau. So Kandinsky taught me how to achieve the effects that I wanted with a palette knife... My main difficulty was I could not paint fast enough. My pictures are all moments of life - I mean instantaneous visual experiences, generally noted very rapidly and spontaneously. When I begin to paint, it's like leaping suddenly into deep waters, and I never know beforehand whether I will be able to swim. Well, it was Kandinsky who taught me the technique of swimming. I mean that he has taught me to work fast enough, and with enough self - assurance, to be able to achieve this kind of rapid and spontaneous recording of moments of life."

In 1911 Münter, along with Wassily Kandinsky, and Franz Marc founded the avant - garde expressionist group known as Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider). Within the group, artistic approaches and aims varied amongst artists; however, the artists shared a common desire to express spiritual truths through their art. Many believed in the promotion of modern art; the connection between visual art and music; the spiritual and symbolic associations of color; and a spontaneous, intuitive approach to painting in its move toward abstraction.

During World War I the couple left Germany to take refuge in Switzerland, but since Kandinsky was Russian he was forced to return to Moscow in

1914. He divorced his estranged wife, his cousin, Anja Chimiakin, and

remarried while in Russia and never saw Münter again. In the fall

of 1917 Münter moved to Copenhagen. She returned to Germany

following the war but was relatively inactive in the arts again until

after 1928 and the development of a relationship with Johannes Eichner.

In 1931 she moved back to her house in Murnau with Eichner. During World War II she hid Kandinsky's works and those of other members of the Blue Rider from the Nazis.

In 1956, she received the Culture Prize of the City of Munich. In 1960,

Münter's work was exhibited for the first time in the U.S, and in

1961 at the Mannheim Kunsthalle. Münter lived out the rest of her

life in Murnau, traveling back and forth to Munich. She died, in her

home, on 19 May 1962 in Murnau am Staffelsee. Münter

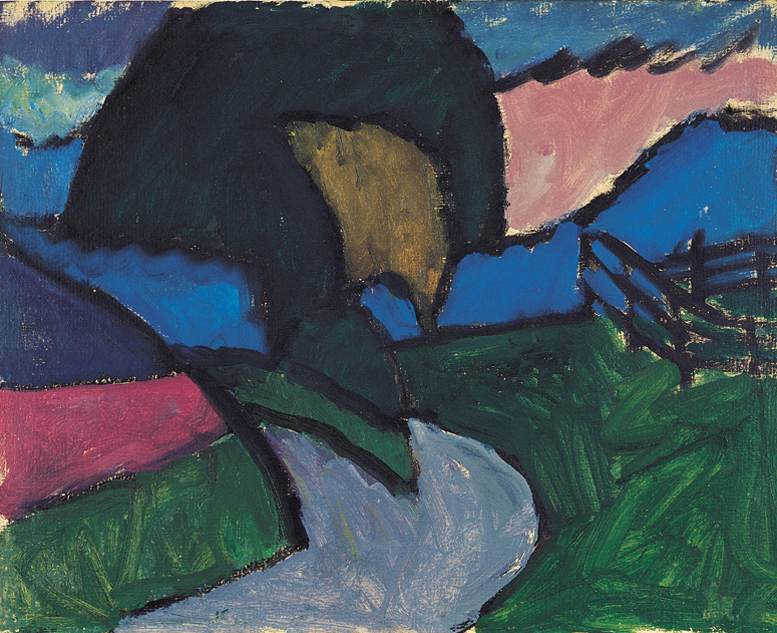

readily fit into small subgroups of artists active in progressively

transforming late Impressionist, Neo-Impressionist, and Jugendstil painting

into the more radical, non-naturalistic art we today identify as

Expressionism. Early on, Münter took a tremendous interest in

landscape. Münter's landscape paintings employ a radical

Jugendstil or Art Nouveau simplicity

and suggestive symbolist mode with softly muted colors, collapsed

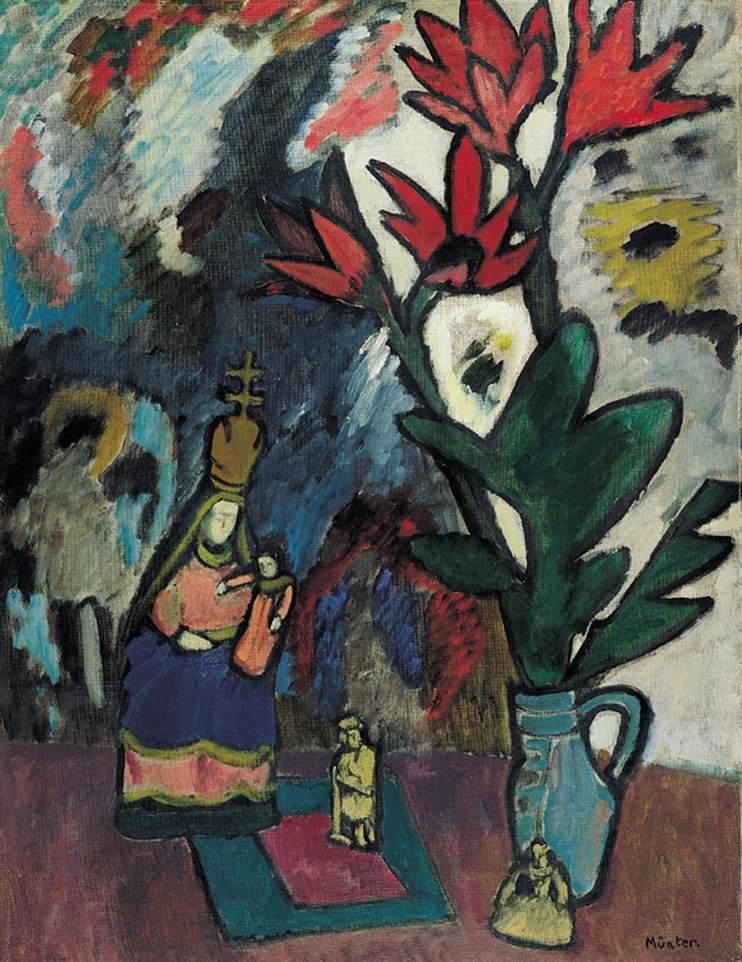

pictorial space, and flattened forms. Münter chose to explore the

world of children. Using colorful prints of children and toys,

Münter shows precision and simplicity of form in her rejection of

symbolic content. By

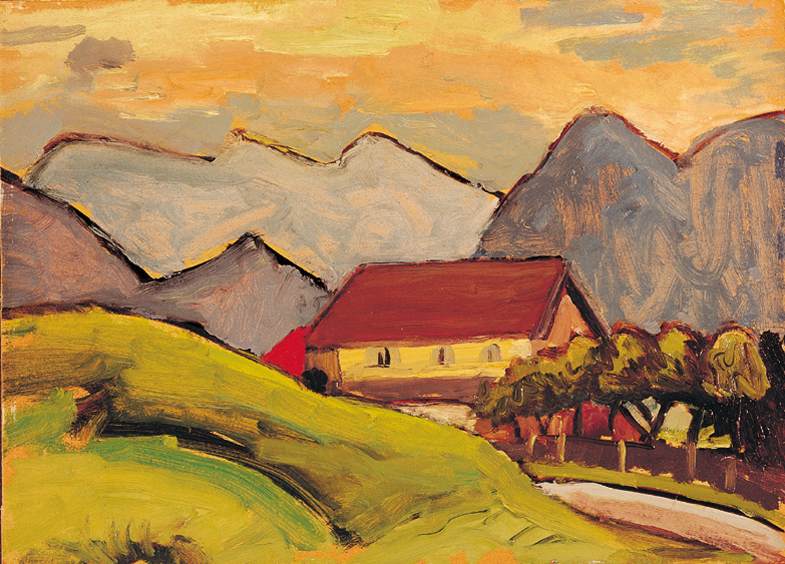

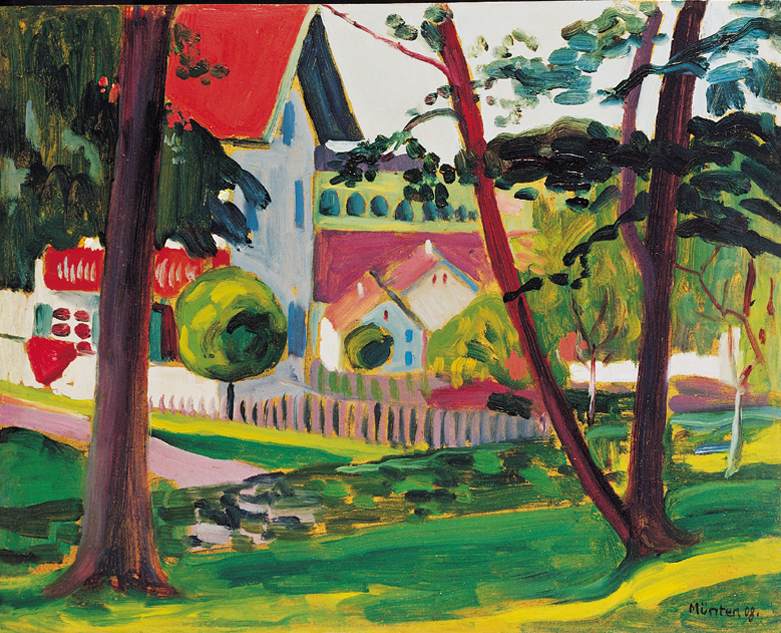

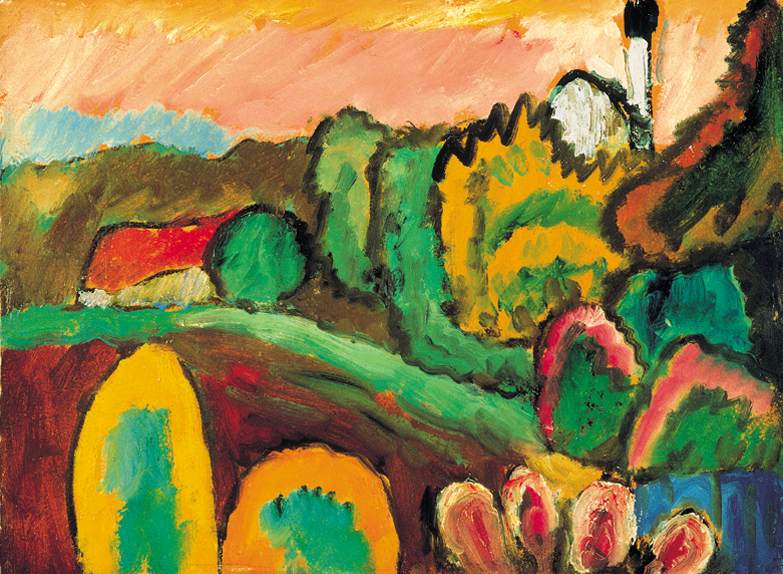

1908, Münter's work began to change. Heavily influenced by Matisse

and Fauvism, Gauguin, and Van Gogh, Münter's work began to

represent a presentation of an extract. Münter took refuge in the

small Bavarian market town of Murnau. Murnau was a village untouched by

industrialization, progress, and technology. It was here, in

Münter's landscape paintings where she placed an emphasis on

nature, imaginative landscape, as well as a desire to oppose German

modernity. Münter's landscapes are unusual with their pallet of

blues, greens, yellows, and pinks. It is color that plays an enormous

role in Münter's early works. Color is used to evoke feeling both

picturesque and inviting, imaginative, and fantasy like. In

Münter's landscapes, she presented the village and the countryside

as manifestations of human life. In Münter's landscapes, there is

a constant interaction and coexistence with nature. In

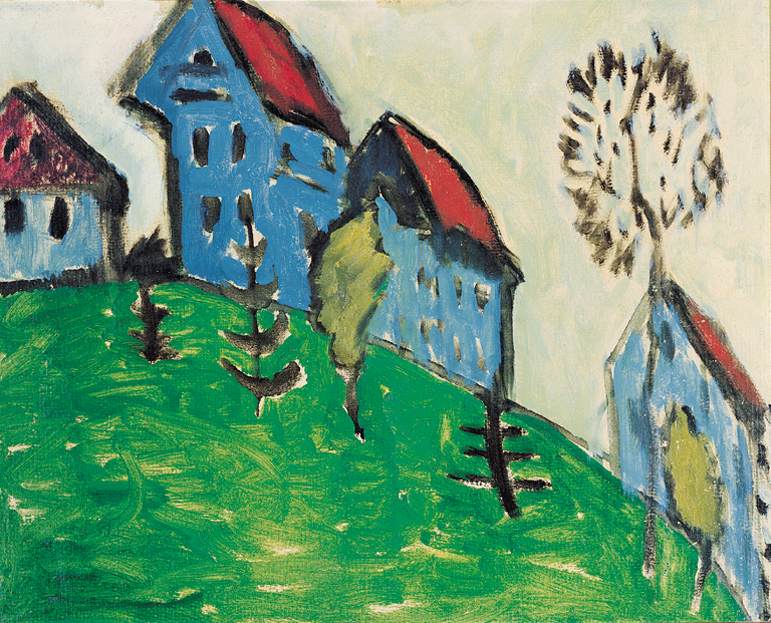

1911, with the establishment of Der Blaue Reiter group, Münter's

work evolved stylistically once again. In her work, there was a leap

from copying nature, more or less impressionistically, to feeling the

content, abstracting, and drawing out an extract. There came an

interest in painting the spirit of the modern civilization, it's social

and political turmoils, its turn to materialism and alienation.

Münter noted that pictures are all moments of life, instantaneous

visual experiences, generally rapid and spontaneous. Münter's

structures each have their own identity, their own shape, and their own

function. For

Münter, it is the use of color that carries out these notions. The

German Expressionists moved towards primitive art as a model of

abstraction, or non representational, non-academic, non-bourgeois art.

The German artist looks not for harmony of outward appearance, but much

more for the mystery hidden behind the external form. He or she is

interested in the soul of things, and wants to lay this bare.