<Back to Index>

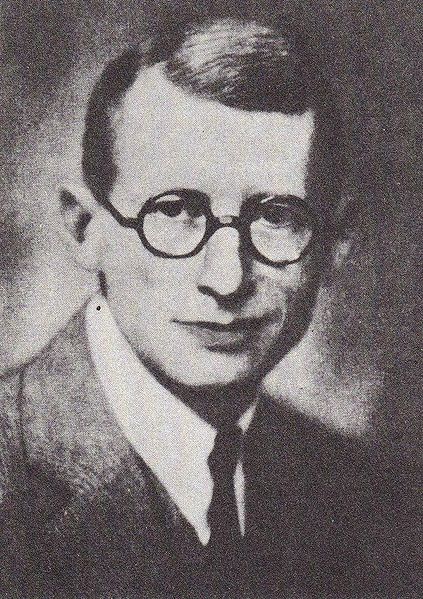

- Paleoanthropologist Davidson Black, 1884

- Painter Alexander Joseph Rummler, 1867

- Deputy Supreme Allied Commander Europe General Richard Nelson Gale, 1896

PAGE SPONSOR

Davidson Black, FRS (born July 25, 1884, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, died March 15, 1934, Beijing, China) was a Canadian paleoanthropologist, best known for his naming of Sinanthropus pekinensis (now Homo erectus pekinensis). He was Chairman of the Geological Survey of China and a Fellow of the Royal Society. He was known as 步達生 (pinyin: Bù Dáshēng) in China.

Davidson Black was born in 1884, in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. When he was a child, he would spend many summers near or on the Kawartha lakes. As a teenager, he would carry heavy loads of supplies for the Hudson's Bay Company. He also enjoyed collecting fossils along the banks of the Don River. He also became friends with First Nations people, and learned one First Nations language. Black also searched unsuccessfully for gold along the Kawartha lakes.

In 1906, Black gained a degree in medical science from the University of Toronto. He continued in school studying comparative anatomy, and in 1909 became an anatomy instructor. In 1914 he spent half a year working under neuroanatomist Grafton Elliot Smith, in Manchester, England. Smith was studying Piltdown Man during this time. This began an interest in human evolution.

In 1917 he joined the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps, where he treated injured returning Canadian soldiers. In 1919 after his discharge from the Canadian Army Medical Corps, he went to China to work at Peking Union Medical College. Starting as Professor of Neurology and Embryology,

he would be promoted to head of the anatomy department in 1924. He

planned to search for human fossils in 1926, though the College

encouraged him to concentrate on teaching. During this period Johan Gunnar Andersson, who had done excavations near Dragon Bone Hill (Zhoukoudian)

in 1921, learned in Sweden of Black's fossils examination. He gave

Black two human-similar molars to examine. The following year, with a

grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, Black began his search around Zhoukoudian. During this time, though military unrest involving the National Revolutionary Army caused many western Scientists to leave China, Davidson Black and his family stayed. Black

then launched a large scale investigation at the site. He was appointed

primary coordinator. As such, he appointed both Caucasian and Chinese

scientists. In summer 1926, two molars were discovered by Otto Zdansky,

who headed the excavations and who described them in 1927 (Bulletin of the Geolocical Survey, China) as fossils of genus Homo. Black thought they belonged to a new human species and named them Sinanthropus pekinensis.

He put this tooth in a locket, which was placed around his neck. Later,

he presented the tooth to the Rockefeller Foundation, which wanted more

specimens before further grants would be given. During

November 1928, a lower jaw and several teeth and skull fragments were

discovered. His findings greatly expanded the knowledge of human

evolution.

Black presented this to the Foundation, which granted him $80,000. This

grant continued the investigation and Black established the Cenozoic Research Laboratory with

it. Later another excavator found a skull. More specimens were found.

Black would frequently examine these late into the night. Alas,

most of the original bones were lost in the process of shipping them

out of China for safe-keeping during the beginning of World War II. The

Japanese gained control of the Peking Union Medical Center during the

war, where the laboratory containing all the fossils was ransacked and

all the remaining specimens were confiscated. To this day, the fossils

have not been found and no one is sure if they were stolen or

legitimately lost. Only the plaster imprints, which were in Beijing at

the time, were left. In

1934, he was hospitalized due to heart problems but continued working

upon his release; these heart problems killed him. He died in his

office with the fossils of the Peking Man beside him. He was 49 years of age.

Fellow researchers were skeptical of Sinanthropus pekinensis as

a distinctive species and genus. The reasons were the fact that the

claim of a new species was originally based on a single tooth. Later

the species was categorized as a subspecies of Homo erectus.