<Back to Index>

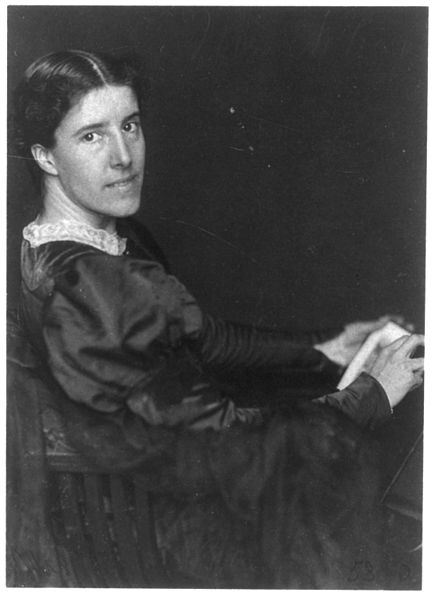

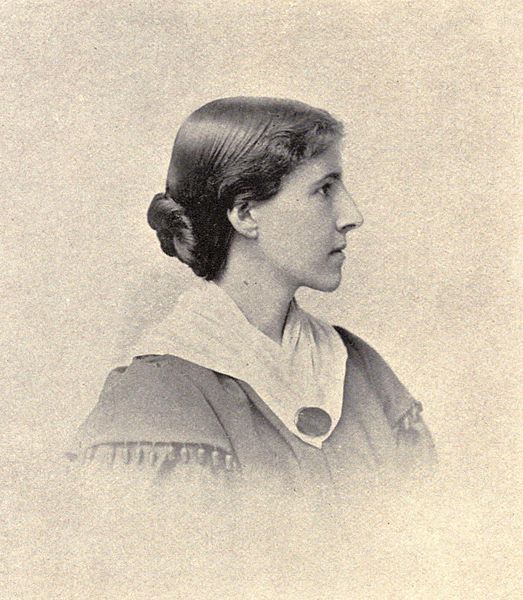

- Sociologist Charlotte Perkins Gilmann 1860

- Composer Leoš Janáček, 1854

- 6th President of Singapore Sellapan Ramanathan, 1924

PAGE SPONSOR

Charlotte Perkins Gilman (July 3, 1860 – August 17, 1935) was a prominent American sociologist, novelist, writer of short stories, poetry, and nonfiction, and a lecturer for social reform. She was a utopian feminist during a time when her accomplishments were exceptional for women, and she served as a role model for future generations of feminists because of her unorthodox concepts and lifestyle. Her best remembered work today is her semi-autobiographical short story The Yellow Wallpaper which she wrote after a severe bout of postpartum psychosis.

Charlotte was born on July 3, 1860, in Hartford, Connecticut, to Mary Perkins (formerly Mary Fitch Westcott) and Frederic Beecher Perkins. She only had one brother, Thomas Adie, who was fourteen months older, because a physician advised Mary Perkins that she might die if she bore other children. During Charlotte's infancy, her father moved out and abandoned his wife and children, leaving them in an impoverished state. Since their mother was unable to support the family on her own, the Perkins were often in the presence of aunts on her father's side of the family, namely Isabella Beecher Hooker, a suffragist, Harriet Beecher Stowe (author of Uncle Tom's Cabin) and Catharine Beecher.

At the age of five she taught herself to read because her mother was ill. Gilman's mother was not affectionate with her children. To keep them from getting hurt as she had been, she forbade her children to make strong friendships or read fiction. In her autobiography, The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Gilman wrote that her mother showed affection only when she thought her young daughter was asleep. Although she lived a childhood of isolated, impoverished loneliness, she unknowingly prepared herself for the life that lay ahead by frequently visiting the public library and studying ancient civilizations on her own. Additionally, her father's love for literature influenced her, and years later he contacted her with a list of books he felt would be worthwhile for her to read.

Much

of Gilman's youth was spent in Providence, Rhode Island. What friends

she had were mainly male, and she was unashamed to call herself a

"tomboy". She attended seven different public schools, and was a correspondent student of the Society to Encourage Studies at Home but only studied until she was fifteen. Her

natural intelligence and breadth of knowledge always impressed her

teachers, who were nonetheless disappointed in her because she was a

poor student. Her

favorite subject was "natural philosophy", especially what later become

known as physics. In 1878, the eighteen year old enrolled in classes at

the Rhode Island School of Design, and subsequently supported herself as an artist of trade cards. She was a tutor, and encouraged others to expand their artistic creativity. She was also a painter. In 1884, she married the artist Charles Walter Stetson after initially declining his proposal because a gut feeling told her it was not the right thing for her. Their

only child, Katharine Beecher Stetson, was born the following year.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman suffered a very serious bout of post-partum

depression in the months after Katharine's birth. This was an age in

which women were seen as "hysterical" and "nervous" beings; thus, when

a woman claimed to be seriously ill after giving birth, her claims were

sometimes dismissed as being invalid. In

1888, Charlotte separated from her husband — a rare occurrence in the

late nineteenth century, but one that was necessary for the improvement

of her mental health. The two legally divorced in 1894. Following the separation, Charlotte moved with her daughter to Pasadena, California, where

she became active in several feminist and reformist organizations such

as The Pacific Coast Woman's Press Association, the Woman's Alliance,

the Economic Club, the Ebell Society, the Parents Association, and the

State Council of Women, in addition to writing and editing the Bulletin, a journal put out by one of the previously mentioned organizations. In

1894, Gilman sent her daughter west to live with her husband and his

second wife, Grace Ellery Channing, who was a close friend of Gilman's.

Gilman reported in her memoir that she was happy for the couple, since

Katharine's "second mother was fully as good as the first, [and

perhaps] better in some ways." Gilman

also held progressive views about paternal rights and acknowledged that

her ex-husband "had a right to some of [Katharine's] society" and that

Katharine "had a right to know and love her father." After

her mother died in 1893 Charlotte decided to move back east for the

first time in eight years. She contacted Houghton Gilman, her first

cousin, whom she had not seen in roughly fifteen years, who was a Wall

Street attorney. They began spending a significant amount of time

together almost immediately and became romantically involved. While she

would go on lecture tours, Houghton and Charlotte would exchange

letters and spend as much time as they could together before she left.

In her diaries, she describes him as being "pleasurable" and it is

clear that she was deeply interested in him. From

their wedding in 1900 until 1922, they lived in New York City. Their

marriage was nothing like Charlotte and Walter's. In 1922, Gilman moved

from New York to Houghton's old homestead in Norwich, Connecticut.

Following Houghton's sudden death from a cerebral hemorrhage in 1934,

Gilman moved back to Pasadena, California, where her daughter resided. In January 1932, Gilman was diagnosed with incurable breast cancer. An advocate of euthanasia for the terminally ill, Gilman committed suicide on August 17, 1935 by taking an overdose of chloroform.

In both her autobiography and suicide note, she wrote that she "chose

chloroform over cancer" and she died quickly and quietly.

After moving to Pasadena, Charlotte became active in organizing social reform movements. As a delegate, she represented California in 1896 at both the Suffrage Convention in

Washington, D.C., and the International Socialist and Labor Congress

which was held in England. In 1890, she was introduced to Nationalism, a movement which worked to "end capitalism's greed and distinctions between classes while promoting a peaceful, ethical, and truly progressive human race." Published in the Nationalist magazine, her poem, Similar Cases was

a satirical review of people who resisted social change and she

received positive feedback from critics for it. Throughout that same

year, 1890, she became inspired enough to write fifteen essays, poems,

a novella, and the short story The Yellow Wallpaper. Her career was launched when she began lecturing on Nationalism and gained the public's eye with her first volume of poetry, In This Our World, published in 1893. As

a successful lecturer who relied on giving speeches as a source of

income, her fame grew along with her social circle of similar minded

activists and writers of the feminist movement.

Although it was not the first or longest of her works, without question Gilman's most famous piece is her short story The Yellow Wallpaper, which became a best seller of the Feminist Press. She wrote it on June

6 and 7 of 1890 in her home of Pasadena, and it was printed a year and

a half later in the January 1892 issue of The New England Magazine. Since

its original printing, it has been anthologized in numerous collections

of women's literature, American literature, and textbooks. The

story is about a woman who suffers from mental illness after three

months of being closeted in a room by her husband for the sake of her

health. She becomes obsessed with the room's revolting yellow

wallpaper. Gilman wrote this story to change people's minds about the

role of women in society, illustrating how women's lack of autonomy is

detrimental to their mental, emotional, and even physical well being.

The narrator in the story must do as her husband, who is also her

doctor, demands, although the treatment he prescribes contrasts

directly with what she truly needs — mental stimulation and the freedom

to escape the monotony of the room to which she is confined. The Yellow Wallpaper was

essentially a response to the doctor who had tried to cure her of her

depression through a "rest cure", Dr. S. Weir Mitchell, and she sent

him a copy of the story. Gilman's first book was Art Gems for the Home and Fireside (1888); however, it was her first volume of poetry, In This World (1893), a collection of satirical poems, that first brought her recognition.

During the next two decades she gained much of her fame with lectures

on women's issues, ethics, labor, human rights, and social reform. She

often referred to these themes in her fiction. In 1894 – 95 Gilman served as editor of the magazine The Impress, a literary weekly that was published by the Pacific Coast Women’s Press Association (formerly the Bulletin).

For the twenty weeks the magazine was printed, she was consumed in the

satisfying accomplishment of contributing its poems, editorials, and

other articles. The short lived paper's printing came to an end as a

result of a social bias against her lifestyle which included being an

unconventional mother and a woman who had divorced a man. After

a four month long lecture tour that ended in April 1897, Gilman began

to think more deeply about sexual relationships and economics in

American life, eventually completing the first draft of Women and Economics (1898). The book was published in the following year, and propelled Gilman into the international spotlight. In

1903, she addressed the International Congress of Women in Berlin, and,

the next year, toured in England, Holland, Germany, Austria, and

Hungary. In 1903 she wrote one of her most critically acclaimed books, The Home: Its Work and Influence, which expanded upon Women and Economics,

proposing that women are oppressed in their home and that the

environment in which they live needs to be modified in order to be

healthy for their mental states. In between traveling and writing, her

career as a literary figure was secured. From 1909 to 1916 Gilman single handedly wrote and edited her own magazine, The Forerunner,

in which much of her fiction appeared. By presenting material in her

magazine that would "stimulate thought", "arouse hope, courage and

impatience", and "express ideas which need a special medium", she aimed

to go against the mainstream media which was overly sensational. Over

seven years and two months the magazine produced eighty six issues,

each twenty eight pages long. The magazine had nearly 1,500 subscribers

and featured such serialized works as What Diantha Did (1910), The Crux (1911), Moving the Mountain (1911), and Herland. The Forerunner has been cited as being "perhaps the greatest literary accomplishment of her long career". After its seven years, she wrote hundreds of articles which were submitted to the Louisville Herald, The Baltimore Sun, and the Buffalo Evening News. Her autobiography, The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, which she began to write in 1925, appeared posthumously in 1935. Gilman

married Walter Stetson in 1884, and less than a year later gave birth

to their daughter Katharine. Already susceptible to depression, her

symptoms were exacerbated by marriage and motherhood. A good proportion

of her diary entries from the time she gave birth to her daughter until

several years later describe the oncoming depression that she was to

face. On

April 18, 1887, Gilman wrote in her diary that she was very sick with

"some brain disease" which brought suffering that cannot be felt by

anybody else, to the point that her "mind has given way". To begin, the patient could not even leave her bed, read, write, sew, talk, or feed herself. After

nine weeks, Gilman was sent home with Mitchell’s instructions, “Live as

domestic a life as possible. Have your child with you all the time...

Lie down an hour after each meal. Have but two hours’ intellectual life

a day. And never touch pen, brush or pencil as long as you live.” She

tried for a few months to follow Mitchell's advice, but her depression

deepened, and Gilman came perilously close to a full emotional collapse. Her

remaining sanity was on the line and she began to display suicidal

behavior that involved talk of pistols and chloroform, as recorded in

her husband's diaries. By early summer the couple had decided that a

divorce was necessary for her to regain sanity without affecting the

lives of her husband and daughter. During

the summer of 1888, Charlotte and Katharine spent time in Bristol,

Rhode Island, away from Walter, and it was there where her depression

began to lift. She writes of herself noticing positive changes in her

attitude. She returned to Providence in September. She sold property

that had been left to her in Connecticut, and went with a friend, Grace

Channing, to Pasadena where the cure of her depression can be seen

through the transformation of her intellectual life. Gilman called herself a humanist, and believed the domestic environment oppressed women through the patriarchal beliefs upheld by society. Gilman embraced the theory of reform Darwinism and

argued that Darwin's theories of evolution only presented the male as

the given in the process of human evolution, thus overlooking the

origins of the female brain in society which rationally chose the best

suited mate that they could find. In doing so, Charlotte believed very

seriously that Charles Darwin accidentally

subjugated women by installing male sex selection, which requires

constant sexual contact as opposed to a more periodic sexuality, thus

leading to the oppression of women through rape and violence. Gilman

argued that male aggressiveness and maternal roles for women were

artificial and no longer necessary for survival in post prehistoric

times. She wrote, "There is no female mind. The brain is not an organ

of sex. Might as well speak of a female liver". Her

main argument was that sex and domestic economics went hand in hand; in

order for a woman to survive she was reliant on her sexual assets to

please her husband so that he would bring home the bread. From

childhood young girls are forced into a social constraint that prepares

them for motherhood by the toys that are marketed to them and the

clothes designed for them. She argued that there should be no

difference in the clothes that little girls and boys wear, the toys

they play with, or the activities they do, and described tomboys as

perfect humans who ran around and used their bodies freely and

healthily. Charlotte argued that women's contributions to civilization, throughout history, have been halted because of an androcentric culture. She believed that the female race was the half of humanity that was

underdeveloped, and improvement was necessary to prevent the

deterioration of the human race. Gilman

believed economic independence is the only thing that could really

bring freedom for women, and make them equal to men. In 1898 she

published Women and Economics,

a theoretical treatise which argued, among other things, that women are

subjugated by men, that motherhood should not preclude a woman from

working outside the home, and that housekeeping, cooking, and child

care, would be professionalized. “The

ideal woman", Gilman wrote, "was not only assigned a social role that

locked her into her home, but she was also expected to like it, to be

cheerful and gay, smiling and good humored.” When the sexual - economic

relationship ceases to exist, life on the domestic front would

certainly improve, as frustration in relationships often stems from the

lack of social contact that the domestic wife has with the outside

world. Gilman

became a spokesperson on topics such as women’s perspectives on work,

dress reform, and family. Housework, she argued, should be equally

shared by men and women, and that at an early age women should be

encouraged to be independent. In many of her major works, including

"The Home" (1903), Human Work (1904), and The Man Made World (1911), Gilman also advocated women working outside of the home.

Gilman

believed Americans were giving up their country to immigrants who, she

said, were diluting the nation's reproductive purity. In her day, the racist and ethnocentric assumptions about stages of human

development were widely accepted ideas in the universities. However,

in an effort to gain votes for all women, she spoke out against the

literacy requirements for the right to vote at the national American Women's Suffrage Association convention which took place in 1903 in New Orleans. The Yellow Wallpaper was initially met with a mixed reception. One critic wrote to the Boston Transcript:

“The story could hardly, it would seem, give pleasure to any reader,

and to many whose lives have been touched through the dearest ties by

this dread disease, it must bring the keenest pain. To others, whose

lives have become a struggle against heredity of mental derangement,

such literature contains deadly peril. Should such stories be allowed

to pass without severest censure?” Positive

reviewers describe it as impressive because it is the most suggestive

and graphic account of why women who live monotonous lives go crazy. Although Gilman had gained international fame with the publication of Women and Economics in 1898, by the end of World War I she seemed out of tune with her times. In her autobiography she admitted,

"unfortunately my views on the sex question do not appeal to the Freudian complex

of today, nor are people satisfied with a presentation of religion as a

help in our tremendous work of improving this world." Ann J. Lane writes in Herland and Beyond that “Gilman offered perspectives on major issues of gender with

which we still grapple; the origins of women’s subjugation, the

struggle to achieve both autonomy and intimacy in human relationships;

the central role of work as a definition of self; new strategies for

rearing and educating future generations to create a humane and

nurturing environment.” Recently, she has been criticized for her idea in A Suggestion on the Negro Problem to enlist a civic army of blacks like an AmeriCorps to provide jobs and discipline.