<Back to Index>

- Physiologist Ragnar Arthur Granit, 1900

- Sculptor Émile Antoine Bourdelle, 1861

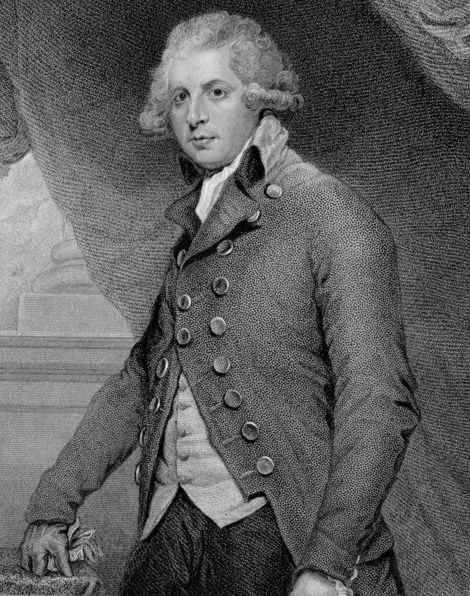

- Playwright and Politician Richard Brinsley Butler Sheridan, 1751

PAGE SPONSOR

Richard Brinsley Butler Sheridan (30 October 1751 – 7 July 1816) was an Irish born playwright and poet and long term owner of the London Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. For thirty - two years he was also a Whig Member of the British House of Commons for Stafford (1780 – 1806), Westminster (1806 – 1807) and Ilchester (1807 – 1812). Such was the esteem he was held in by his contemporaries when he died that he was buried at Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey. He is known for his plays such as The Rivals, The School for Scandal and A Trip to Scarborough.

R.B. Sheridan was born in 1751 in Dublin, Ireland, where his family had a house on then fashionable Dorset Street. While in Dublin Sheridan attended the English Grammar School in Grafton Street. The family moved permanently to England in 1758 when he was age seven. He was a pupil at Harrow School outside London from 1762 to 1768. His mother, Frances Sheridan, was a playwright and novelist. She had two plays produced in London in the early 1760s, though she is best known for her novel The Memoirs of Sidney Biddulph (1761). His father, Thomas Sheridan, was for a while an actor - manager at the Smock Alley Theatre but, following his move to England in 1758, he gave up acting and wrote a number of books concerning education and, especially, the standardisation of the English language in education.

In

1772 Richard Sheridan fought a famous duel against Captain Thomas

Mathews. Mathews had written a newspaper article defaming the character

of Elizabeth Linley, the woman Sheridan intended to marry, and honour

dictated that a duel must be fought. A first duel was fought in London

where they agreed to fight in Hyde park, but finding it too crowded they

went to the Castle Tavern in Henrietta Street, Covent Garden.

Far from its romantic image, the duel was short and bloodless. Mathews

lost his sword and, according to Sheridan, was forced to 'beg for his

life' and sign a retraction of the article. The apology was made public

and Mathews, infuriated by the publicity the duel had received, refused

to accept his defeat as final and challenged Sheridan to another duel.

Sheridan was not obliged to accept this challenge, but would have become

a social pariah if he had not. The second duel, fought in August 1772

at Kingsdown near Bath, was a much more ferocious affair. This time both

men broke their swords but carried on fighting in a 'desperate struggle

for life and honour'. Both were wounded, Sheridan dangerously, being

'borne from the field with a portion of his antagonist's weapon sticking

through an ear, his breast - bone touched, his whole body covered with

wounds and blood, and his face nearly beaten to jelly with the hilt of

Mathews' sword'. Fortunately his remarkable constitution pulled him

through, and eight days after this bloody affair the Bath Chronicle was

able to announce that he was out of danger. Mathews escaped in a post

chaise.

In 1773, Richard Sheridan at age 21 married Elizabeth Ann Linley and set up house in London on a lavish scale with little money and no immediate prospects of any — other than his wife's dowry. The young couple entered the fashionable world and apparently held up their end in entertaining. When Sheridan settled in London, he began writing for the stage. Less than two years later, in 1775, his first play, The Rivals, was produced at London's Covent Garden Theatre. It was a failure on its first night. Sheridan cast a more capable actor for the role of the comic Irishman for its second performance, and it was a smash which immediately established the young playwright's reputation and the favour of fashionable London. It has gone on to become a standard of English literature.

Shortly after the success of The Rivals, Sheridan and his father - in - law Thomas Linley the elder, a successful composer, produced the opera, The Duenna. This piece was accorded such a warm reception that it played for seventy - five performances.

In 1776, Sheridan, his father - in - law, and one other partner, bought a half interest in the Drury Lane theatre and, two years later, bought out the other half. Sheridan was the manager of the theatre for many years, and later became sole owner with no managerial role.

His most famous play The School for Scandal (Drury Lane, 8 May 1777) is considered one of the greatest comedies of manners in English. It was followed by The Critic (1779), an updating of the satirical Restoration play The Rehearsal, which received a memorable revival (performed with Oedipus in a single evening) starring Laurence Olivier as Mr Puff, opening at the New Theatre on 18 October 1945 as part of an Old Vic Theatre Company season.

Having quickly made his name and fortune, in 1776 Sheridan bought David Garrick's share in the Drury Lane patent, and in 1778 the remaining share. His later plays were all produced there. In 1778 Sheridan wrote The Camp which commented on the ongoing threat of a French invasion of Britain. The same year Sheridan's brother - in - law Thomas Linley,

a young composer who worked with him at Drury Lane Theatre, died in a

boating accident. Sheridan had a rivalry with his fellow playwright Richard Cumberland and included a parody of Cumberland in his play The Critic.

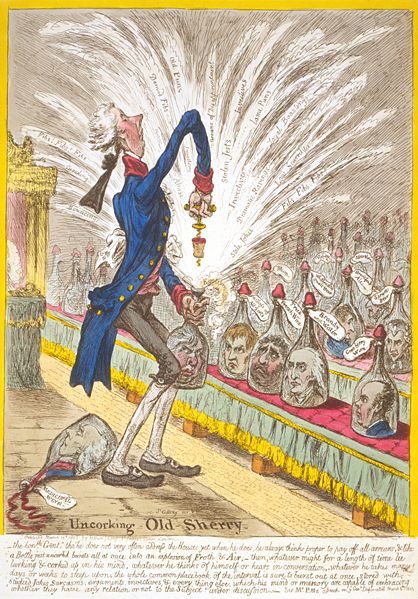

On 24 February 1809 (despite the much vaunted fire safety precautions

of 1794) the theatre burned down. On being encountered drinking a glass

of wine in the street while watching the fire, Sheridan was famously

reported to have said: "A man may surely be allowed to take a glass of

wine by his own fireside."

In 1780, Sheridan entered Parliament as the ally of Charles James Fox on the side of the American Colonials in the political debate of that year. He is said to have paid the burgesses of Stafford five guineas apiece for the honour of representing them. As a consequence, his first speech in Parliament had to be a defence against the charge of bribery.

In 1793 during the debates on the Aliens Act designed to prevent French Revolutionary spies and saboteurs from flooding into the country, Edmund Burke made a speech in which he claimed there were thousands of French agents in Britain ready to use weapons against the authorities. To dramatically emphasise his point he threw down a knife onto the floor of the House of Commons. Sheridan is said to have shouted out "Where's the fork?", which led to much of the house collapsing in laughter.

During the invasion scare of 1803 Sheridan penned an Address to the People:

THEY, by a strange Frenzy driven, fight for Power, for Plunder, and extended Rule — WE, for our Country, our Altars, and our Homes. — THEY follow an ADVENTURER, whom they fear — and obey a Power which they hate — WE serve a Monarch whom we love — a God whom we adore... They call on us to barter all of Good we have inherited and proved, for the desperate Chance of Something better which they promise. — Be our plain Answer this: The Throne WE honour is the PEOPLE'S CHOICE — the Laws we reverence are our brave Fathers' Legacy — the Faith we follow teaches us to live in bonds of Charity with all Mankind, and die with Hope of Bliss beyond the Grave. Tell your Invaders this; and tell them too, we seek no Change; and, least of all, such Change as they would bring us.

He held the posts of Receiver - General of the Duchy of Cornwall (1804 – 1807) and Treasurer of the Navy (1806 – 1807).

When he failed to be re-elected to Parliament in 1812, after 32 years, his creditors closed in on him and his last years were harassed by debt and disappointment. On hearing of his debts, the American Congress offered Sheridan £20,000 in recognition of his efforts to prevent the American War of Independence. The offer was refused.

In December 1815 he became ill, largely confined to bed. Sheridan died in poverty, and was buried in the Poets' Corner of Westminster Abbey; his funeral was attended by dukes, earls, lords, viscounts, the Lord Mayor of London, and other notables.

In 1825 the Irish writer Thomas Moore published a two - volume sympathetic biography Memoirs of the Life of Richard Brinsley Sheridan which became a major influence on subsequent perceptions of him.

He and his wife had two children: Thomas Sheridan and Edith Marcia Caroline Sheridan.