<Back to Index>

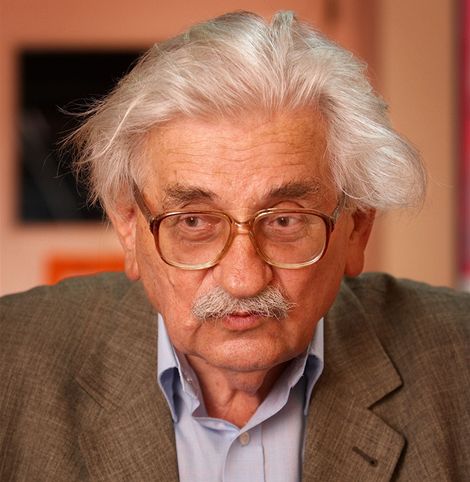

- Writer and Journalist Ludvík Vaculík, 1926

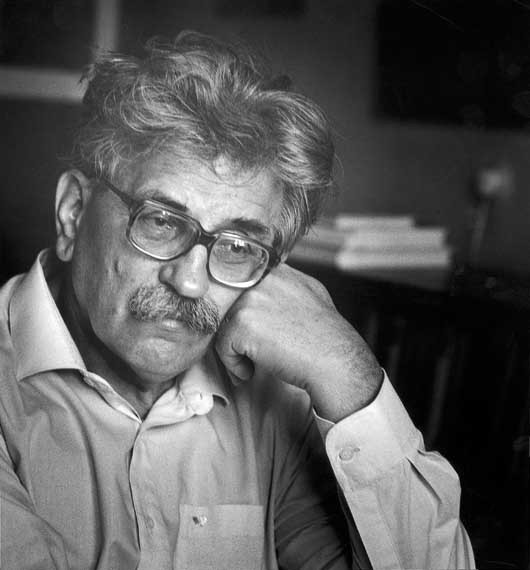

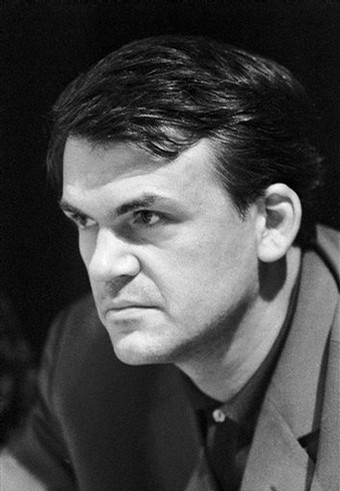

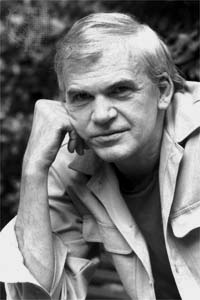

- Novelist Milan Kundera, 1929

PAGE SPONSOR

Ludvík Vaculík (23 July 1926, Brumov - 6 June 2015) was a Czech writer and journalist. A prominent samizdat writer, he is most famous as the author of the "Two Thousand Words" manifesto of June 1968.

President of Czechoslovakia and Communist Party leader Antonín Novotný and his fellow conservatives had begun taking a more repressive approach toward intellectuals and writers after the Six Day War of May 1967. The following month, Vaculík, then still a member of the Communist Party, attended the Fourth Congress of the Union of Writers. Others in attendance included communists Pavel Kohout, Ivan Klíma, and Milan Kundera, as well as non - Party member Václav Havel. Vaculík made an inflammatory speech in which he rejected the leading role of the party as unnecessary and criticized it for its restrictive cultural policies and failure to address social issues. Havel recalled the mixed response of the fellow writers to Vaculík's remarks: on the one hand, they were “delighted that someone had spoken the truth… but [their] delight was tempered by doubts about whether direct confrontation on the political level would lead anywhere, and by fears that it could stimulate a counterattack by the power center.” Novotný and his supporters did indeed try to bring the writers' union under their control after the congress, but failed. Vaculík's and other writers' speeches at the conference, with their anti - Novotný sentiments, increased the gap between the conservative Novotný supporters and more moderate members of the party leadership, a division that would contribute to Novotný's eventual fall.

Vaculík was among the most progressive members of the Communist Party and thereby more radical than Alexander Dubček, who had become Party leader in January 1968. Hence, Vaculík and others generally felt that the reforms of the April Action Program were the minimum necessary and that they should be quickly and firmly enforced. In hopes of influencing voters in upcoming party congress elections, Vaculík released the manifesto "Two Thousand Words to Workers, Farmers, Scientists, Artists, and Everyone" in several major Prague newspapers, complete with signatures of other public figures. The date was 27 June 1968, the day after preliminary censorship was abolished by the national assembly.

In the "Two Thousand Words," Vaculík asked that the public “demand the resignation of people who have misused their power” by criticism, demonstrations, and strikes. He also expressed concern over the "recent apprehension" regarding the reforms due to "the possibility that foreign forces" - those of the Warsaw Treaty Organization - "may intervene in Czechoslovakia's internal development." If this were to happen, Vaculík argued:

… the only thing we can do is to hold our own and not indulge in any provocation. We can assure our government - with weapons if need be - as long as it does what we give it a mandate to do.

In case of invasion, Vaculík felt that the people of Czechoslovakia should defend themselves and their government (so long as it remained acceptably reformist) with force.

Despite the overall moderate

tone and Marxist -

Leninist orthodoxy, the "Two

Thousand Words" called for action on the part of

the public in case of military intervention and

therefore denied the leading role of the party, as

Vaculík's 1967 speech had. It was popular

throughout Czechoslovakia with both intellectuals

and workers, and its popularity only increased

after the party officially condemned it. It also

significantly increased the concerns of the Soviet

Union. Following the “Two Thousand Words,” Leonid Brezhnev's party

leadership, seeing a situation similar to that in 1956 Hungary developing, used the

term "counterrevolution" to describe the Prague Spring for

the first time. If a counterrevolution was

taking place (and the Soviet Union was

increasingly disposed to categorizing the events

in Czechoslovakia as such, as other radicals

continued to act and Dubček failed to gain their

confidence), socialism as

the Soviet Union saw it was threatened and

invasion by Warsaw Treaty Organization troops, as

occurred 20 – 21 August 1968, was deemed

justified. This policy of the acceptability of

using force wherever socialism was thought to be

threatened would become known as the Brezhnev doctrine,

and Vaculík's "Two Thousand Words" was an integral

step toward this early application of it.

After Gustáv Husák came to power in 1969 and censorship increased, Vaculík (now no longer a party member) was part of the circle of dissident writers in Czechoslovakia. In 1973, he started Edice Petlice (Edition Padlock), a samizdat series that he ran until 1979. Others followed with their own series, despite harassment from the party's secret police. Some samizdat authors, including Vaculík, were also published in the west.

The core of the samizdat authors eventually developed and signed the foundation document of Charter 77; Vaculík attended the second of the planning meetings in December 1976. On 6 January 1977, Vaculík, along with Havel and Pavel Landovský, an actor, attempted to take a copy of the charter to the post office to mail to the Czechoslovak government. Their car was pulled over by the Party secret police, and all three were taken in for interrogation. Other signatories were subsequently subjected to interrogations and searches of their homes, as well.

In late 1978, however, Vaculík published the article "Remarks on Courage," a piece that helped set the tone for criticism of charterists. Of the original signatories, most were from the intelligentsia in Prague and Brno, and Vaculík and others warned against them becoming so isolated that average citizens could no longer relate to Charter 77. His criticism worked against a mythologization of the Charter and ensured a continued discussion of its position and role.

Vaculík continued to write;

the official ban on his works was lifted in late

1989. He had a weekly column in Lidové Noviny that

featured feuilletons addressing

various Czech political and cultural issues, just

as much of his underground work during Communism

had.

Milan Kundera (born 1 April 1929), is a writer of Czech origin who has lived in exile in France since 1975, where he became a naturalized citizen in 1981. He is best known as the author of The Unbearable Lightness of Being, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, and The Joke. Kundera has written in both Czech and French. He revises the French translations of all his books; these therefore are not considered translations but original works. His books were banned by the Communist regimes of Czechoslovakia until the downfall of the regime in the Velvet Revolution of 1989.

Kundera was born in 1929 at Purkyňova ulice, 6 (6 Purkyňova Street) in Brno, Czechoslovakia, to a middle class family. His father, Ludvík Kundera (1891 – 1971), once a pupil of the composer Leoš Janáček, was an important Czech musicologist and pianist who served as the head of the Janáček Music Academy in Brno from 1948 to 1961. Milan learned to play the piano from his father; he later studied musicology and musical composition. Musicological influences and references can be found throughout his work; he has even gone so far as to include musical notation in the text to make a point. Kundera is a cousin of Czech writer and translator Ludvík Kundera. He belonged to the generation of young Czechs who had had little or no experience of the pre - war democratic Czechoslovak Republic. Their ideology was greatly influenced by the experiences of World War II and the German occupation. Still in his teens, he joined the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia which seized power in 1948. He completed his secondary school studies in Brno at Gymnázium třída Kapitána Jaroše in 1948. He studied literature and aesthetics at the Faculty of Arts at Charles University in Prague. After two terms, he transferred to the Film Faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague, where he first attended lectures in film direction and script writing.

In 1950, his studies were briefly interrupted by political interferences. He and writer Jan Trefulka were expelled from the party for "anti - party activities." Trefulka described the incident in his novella Pršelo jim štěstí (Happiness Rained On Them, 1962). Kundera also used the incident as an inspiration for the main theme of his novel Žert (The Joke, 1967). After Kundera graduated in 1952, the Film Faculty appointed him a lecturer in world literature. In 1956 Milan Kundera was readmitted into the Party. He was expelled for the second time in 1970. Kundera, along with other reform communist writers such as Pavel Kohout, were partly involved in the 1968 Prague Spring. This brief period of reformist activities was crushed by the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968. Kundera remained committed to reforming Czech communism, and argued vehemently in print with fellow Czech writer Václav Havel, saying, essentially, that everyone should remain calm and that "nobody is being locked up for his opinions yet," and "the significance of the Prague Autumn may ultimately be greater than that of the Prague Spring." Finally, however, Kundera relinquished his reformist dreams and moved to France in 1975. He taught for a few years in the University of Rennes. He was stripped of Czechoslovak citizenship in 1979; he has been a French citizen since 1981.

He maintains contacts with Czech and Slovak

friends in his homeland, but rarely

returns and always does so incognito.

Although his early poetic works are staunchly pro-communist, his novels escape ideological classification. Kundera has repeatedly insisted on being considered a novelist, rather than a political or dissident writer. Political commentary has all but disappeared from his novels (starting specifically after The Unbearable Lightness of Being) except in relation to broader philosophical themes. Kundera's style of fiction, interlaced with philosophical digression, greatly inspired by the novels of Robert Musil and the philosophy of Nietzsche, is also used by authors Alain de Botton and Adam Thirlwell. Kundera takes his inspiration, as he notes often enough, not only from the Renaissance authors Giovanni Boccaccio and Rabelais, but also from Laurence Sterne, Henry Fielding, Denis Diderot, Robert Musil, Witold Gombrowicz, Hermann Broch, Franz Kafka, Martin Heidegger, and perhaps most importantly, Miguel de Cervantes, to whose legacy he considers himself most committed.

Originally, he wrote in Czech. From 1993 onwards, he has written his novels in French. Between 1985 and 1987 he undertook the revision of the French translations of his earlier works. As a result, all of his books exist in French with the authority of the original. His books have been translated into many languages.

In his first novel, The Joke (1967), he gave a satirical account of the nature of totalitarianism in the Communist era. Kundera was quick to criticize the Soviet invasion in 1968. This led to his blacklisting in Czechoslavakia and his works being banned there.

Kundera's second novel first published in French as La vie est ailleurs in 1973. The book was first published in Czech as Život je jinde, by 68 Publishers Toronto in 1979). Life Is Elsewhere is set in Czechoslovakia before, during and after the Second World War and chronicles the life of Jaromil, a character who has dedicated his life to poetry.

In 1975, Kundera moved to France. There he published The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (1979) which told of Czech citizens opposing the communist regime in various ways. An unusual mixture of novel, short story collection and author's musings, the book set the tone for his works in exile. Critics have noted the irony that the country that Kundera seemed to be writing about when he talked about Czechoslovakia in the book, "is, thanks to the latest political redefinitions, no longer precisely there" which is The "kind of disappearance and reappearance" Kundera explores in the book. Published in Czech (Kniha smíchu a zapomnění) in April 1981 by 68 Publishers Toronto.

In 1984, he published The Unbearable Lightness of Being, his most famous work. The book chronicled the fragile nature of the fate of the individual and theorized that a single lifetime is insignificant in the scope of Nietzsche's concept of eternal return, because in an infinite universe, everything is guaranteed to recur infinitely. In 1988, American director Philip Kaufman released a film version of the novel.

In 1990, Kundera published Immortality.

The novel, his last in Czech, was more

cosmopolitan than its predecessors. Its content

was more explicitly philosophical, as well as less

political. It would set the tone for his later

novels.

Kundera's characters are often explicitly identified as figments of his own imagination, commenting in the first person on the characters in entirely third person stories. Kundera is more concerned with the words that shape or mould his characters than with the characters' physical appearance. In his non - fiction work, The Art of the Novel, he says that the reader's imagination automatically completes the writer's vision. He, as the writer, wishes to focus on the essential insofar as the physical is not critical to an understanding of the character. For him the essential may not include the physical appearance or even the interior world (the psychological world) of his characters. Other times, a specific feature or trait may become the character's idiosyncratic focus.

François Ricard suggested that Kundera conceives with regard to an overall oeuvre, rather than limiting his ideas to the scope of just one novel at a time. His themes and meta - themes exist across the entire oeuvre. Each new book manifests the latest stage of his personal philosophy. Some of these meta - themes include exile, identity, life beyond the border (beyond love, beyond art, beyond seriousness), history as continual return, and the pleasure of a less "important" life. Many of Kundera's characters are intended as expositions of one of these themes at the expense of their fully developed humanity. Specifics in regard to the characters tend to be rather vague. Often, more than one main character is used in a novel, even to the extent of completely discontinuing a character and resuming the plot with a brand new character. As he told Philip Roth in an interview in The Village Voice: "Intimate life [is] understood as one's personal secret, as something valuable, inviolable, the basis of one's originality.

Kundera's early novels explore the dual tragic and comic aspects of totalitarianism. He does not view his works, however, as political commentary. "The condemnation of totalitarianism doesn't deserve a novel," says Kundera. According to the Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes, "What he finds interesting is the similarity between totalitarianism and "the immemorial and fascinating dream of a harmonious society where private life and public life form but one unity and all are united around one will and one faith..." In exploring the dark humor of this topic, Kundera seems deeply influenced by Franz Kafka.

Kundera considers himself to be a writer without a message. For example, in the Sixty - three Words, a chapter in The Art of the Novel, Kundera recounts an episode when a Scandinavian publisher hesitated about going ahead with the publication of The Farewell Party because of the apparent anti - abortion message contained in the novel. Kundera explains that not only was the publisher wrong about the existence of such a message in the work, but, "...I was delighted with the misunderstanding. I had succeeded as a novelist. I succeeded in maintaining the moral ambiguity of the situation. I had kept faith with the essence of the novel as an art: irony. And irony doesn't give a damn about messages!"

He also digresses into musical matters,

analyzing Czech folk music, quoting from Leoš Janáček and Bartók. Further in

this vein, he interpolates musical excerpts into the

text (for example, in The

Joke), or discusses Schoenberg and atonality.

On October 13, 2008, the Czech weekly Respekt prominently publicized an investigation carried out by the Czech Institute for Studies of Totalitarian Regimes, which alleged Kundera denounced to the police a young Czech pilot, Miroslav Dvořáček. The accusation was based on a police station report from 1950 which gave "Milan Kundera, student, born 1.4.1929" as the informant about the presence of Dvořáček at a student dormitory, information about his defection from military service and residence in Germany is attributed to Iva Militká. The target of the subsequent arrest, Miroslav Dvořáček, had fled Czechoslovakia after being ordered to join the infantry in the wake of a purge of the flight academy and returned to Czechoslovakia as an agent of a spy agency organized by Czechoslovak exiles. The police report does not mention his activity as an agent. Dvořáček returned secretly to the student dormitory of a friend's former sweetheart, Iva Militká. Militká was dating (and later married) a fellow student Ivan Dlask, and Dlask knew Kundera. The police report states that Militká told Dlask who told Kundera who told the police of Dvořáček's presence in town. Although the communist prosecutor sought the death penalty, Dvořáček was sentenced to 22 years (as well as being charged 10,000 crowns, forfeiting property, and being stripped of civic rights) and ended up serving 14 years in labor camp, with some of that time spent in a uranium mine, before being released.

After Respekt's report (which states that Kundera did not know Dvořáček), Kundera denied turning Dvořáček in to the police, stating he did not know him at all, and could not even recollect "Militská". This denial was broadcast in Czech, but is available in English transcript only in abbreviated paraphrase. On October 14, 2008, the Czech Security Forces Archive ruled out the possibility that the document could be a fake, but refused to make any interpretation about it. (Vojtech Ripka for the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes said, "There are two pieces of circumstantial evidence [the police report and its sub-file], but we, of course, cannot be one hundred percent sure. Unless we find all survivors, which is unfortunately impossible, it will not be complete", adding both that the signature on the police report matches the name of a man who worked in the corresponding National Security Corps section and, on the other hand, that a police protocol is missing.)

Dvořáček still believes he was betrayed by Iva Militká; his wife said she doubted the "so-called evidence" against Kundera. Dlask, who according to the police report told Kundera of Dvořáček's presence, died in the 1990s. He had told his wife Militká that he had mentioned Dvořáček's arrival to Kundera. Two days after the incident became widely publicized, a counterclaim was made by literary historian Zdeněk Pešat. He said that Dlask was the informant in the case, and Dlask had told him that he had "informed the police." Pešat, then a member of a branch of Czechoslovak Communist Party, said he believed that Dlask informed on Dvořáček to protect his girlfriend from sanctions for being in contact with an agent - provocateur. As Kundera's name still appears as the informer on the police report, this still leaves open the possibility that Kundera informed on Dvořáček to the police (and not the Communist Party branch) separately from Dlask, or had been set up by Dlask to do the deed itself.

In the first person postscript to Life Is Elsewhere, Kundera (writing as himself) defends his protagonist: he is "a monster. But his monstrosity is potentially contained in us all. It is in me." The protagonist had, among other things, denounced to the authorities a young man about to flee Czechoslovakia. Kundera has since expressed that “The characters in my novels are my own unrealized possibilities.... The novel is not the author’s confession.”

The German newspaper Die Welt has compared Kundera to Günter Grass, the Nobel Prize winner, who in 2006 was revealed to have been drafted into the Waffen - SS in the Second World War. Ivan Klima wrote in the daily Lidové noviny: "From a reader’s perspective it may well be true that if we are disappointed in someone we believed in and admired, our feelings are hurt and our trust is shaken. However, none of this should be used to excuse or exculpate our own misdeeds." Václav Havel did not believe the story and, on 3 November 2008, eleven internationally well known writers came to Kundera's defense, including Salman Rushdie, Fernando Arrabal, Philip Roth, Carlos Fuentes, Gabriel García Márquez, J.M. Coetzee, Orhan Pamuk, Jorge Semprún and Nadine Gordimer.

In 1985, Kundera received the Jerusalem Prize. His acceptance address is printed in his essay collection The Art of the Novel. He has also been mentioned as a contender for the Nobel Prize for literature. He won The Austrian State Prize for European Literature in 1987. In 2000, he was awarded the international Herder Prize. In 2007, he was awarded the Czech State Literature Prize. In 2010, he was made an honorary citizen of his hometown, Brno. In 2011, he received the Ovid Prize.