<Back to Index>

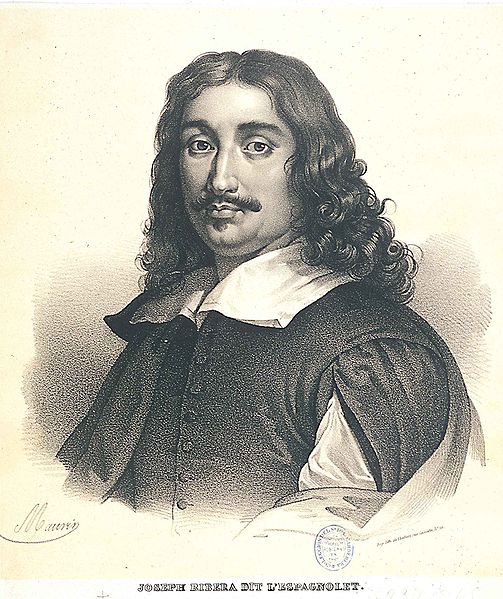

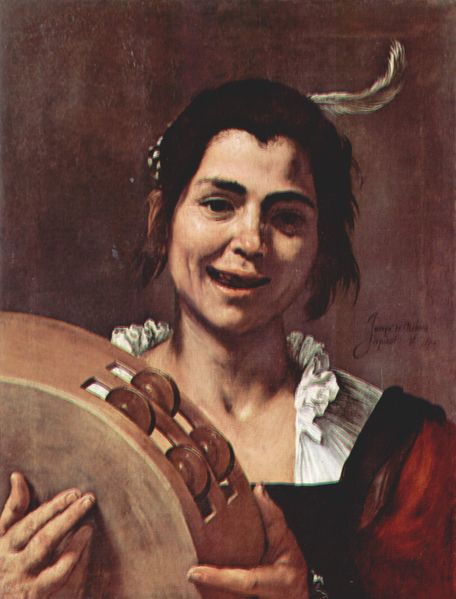

- Painter Jusepe de Ribera (Lo Spagnoletto), 1591

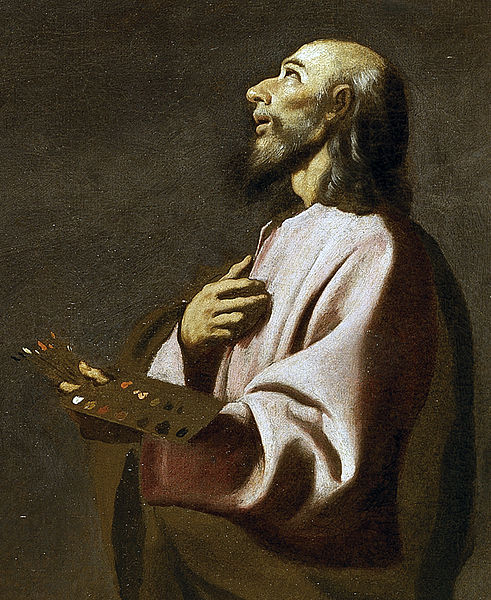

- Painter Francisco de Zurbarán, 1598

PAGE SPONSOR

Jusepe de Ribera, probably an italianization of Josep de Ribera (January 12, 1591 – September 2, 1652) was a Spanish Tenebrist painter and printmaker, also known as José de Ribera in Spanish and as Giuseppe Ribera in Italian. He was also called by his contemporaries and early writers Lo Spagnoletto, or "the Little Spaniard". Ribera was a leading painter of the Spanish school, although his mature work was all done in Italy.

Ribera was born near Valencia, Spain, at Xàtiva. He was baptized on February 17, 1591. His father was a shoemaker, perhaps on a large scale. His parents intended him for a literary or learned career, but he neglected these studies and is said to have apprenticed with the Spanish painter Francisco Ribalta in Valencia, although no proof of this connection exists. Longing to study art in Italy, he made his way to Rome via Parma, where he is recorded in 1611. According to one source, a cardinal noticed him drawing from the frescoes on a Roman palace facade, and housed him. Roman artists gave him the nickname "Lo Spagnoletto."

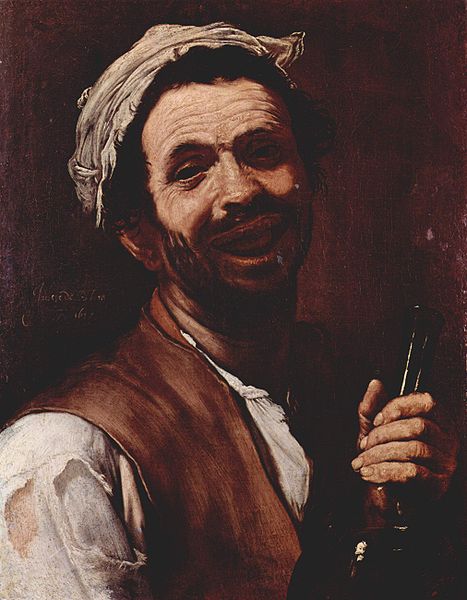

He became a follower of Caravaggio's

style, one of the so-called Tenebrosi, or shadow painters, owing to the

sharp contrasts of light and shade marking their style. He traveled to Parma, where he completed a painting on the subject of Jacob's Ladder, now in the Prado Museum, Madrid. Ribera lived in Rome from 1613 – 16, on the Via Margutta, and associated with other Caravaggisti, including Gerrit van Honthorst and Hendrik ter Brugghen. He then moved to Naples, to avoid his creditors, according to Giulio Mancini, who described him as extravagant. He may also have already arranged his marriage, to the daughter of a Neapolitan painter, Giovanni Bernardino Azzolino, in November, 1616.

The Kingdom of Naples was then part of the Spanish Empire, and ruled by a succession of Spanish Viceroys. Ribera's Spanish nationality aligned him with the small Spanish governing class in the city, and also with the Flemish merchant community, from another Spanish territory, who included important collectors of and dealers in art. Ribera began to sign his work as "Jusepe de Ribera, Español" or "Jusepe de Ribera, Spaniard". He was able to quickly attract the attention of the Viceroy, the Duke of Osuna, also recently arrived, who gave him a number of major commissions, which showed the influence of Guido Reni.

The period after Osuna was recalled in 1620 seems to have been difficult. Few paintings survive from 1620 to 1626; but this was the period in which most of his best prints were produced. These were at least partly an attempt to attract attention from a wider audience than Naples. His career picked up in the late 1620s, and he was accepted as the leading painter in Naples thereafter. Although Ribera never returned to Spain, many of his paintings were taken back by returning members of the Spanish governing class, for example the Duke of Osuna, and his etchings were brought to Spain by dealers. His influence can be seen in Velázquez, Murillo, and most other Spanish painters of the period.

He has been portrayed as selfishly protecting his prosperity, and is reputed to have been the chief in the so-called Cabal of Naples, his abettors being a Greek painter, Belisario Corenzio and the Neapolitan, Giambattista Caracciolo. It is said this group aimed to monopolize Neapolitan art commissions, using intrigue, sabotage of work in progress, and even personal threats of violence to frighten away outside competitors such as Annibale Carracci, the Cavalier d'Arpino, Reni, and Domenichino. All of them were invited to work in Naples, but found the place inhospitable. The cabal ended at the time of Caracciolo's death in 1641.

According to the RKD he is listed as a pupil of Ribalta and in turn his own pupils were Enrico Fiammingo, Francesco Fracanzano, Luca Giordano, and Bartelomeo Passante. He was followed by Giuseppe Marullo and he influenced the painters Agostino Beltrano, Hendrick van Someren, Paolo Domenico Finoglio and Pietro Novelli.

From 1644, Ribera seems to have suffered serious ill health, which

greatly reduced his ability to work himself, although his workshop

continued to produce. In 1647-8, during the Masaniello

rising against Spanish rule, he felt forced to take refuge with his

family in the palace of the Viceroy for some months. In 1651 he sold the

large house he had owned for many years, and when he died on September

2, 1652 he was in serious financial difficulties. His daughter had

married in about 1644 a Spanish nobleman in the administration, who died

soon after.

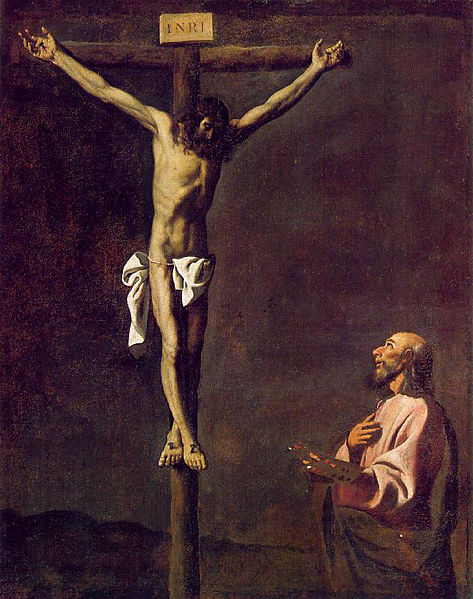

In his earlier style, founded sometimes on Caravaggio and sometimes on the wholly diverse method of Correggio, the study of Spanish and Venetian masters can be traced. Along with his massive and predominating shadows, he retained from first to last a great strength in local coloring. His forms, though ordinary and sometimes coarse, are correct; the impression of his works gloomy and startling. He delighted in subjects of horror. In the early 1630s his style changed away from strong contrasts of dark and light to a more diffused and golden lighting, as can be seen in "The Clubfoot" of 1642. Salvator Rosa and Luca Giordano were his most distinguished followers, who may have been his pupils; others were also Giovanni Do, Enrico Fiammingo, Michelangelo Fracanzani, and Aniello Falcone, who was the first considerable painter of battle pieces.

Among Ribera's principal works could be named "St Januarius

Emerging from the Furnace" in the cathedral of Naples; the "Descent

from the Cross" in the Certosa, Naples, the "Adoration of the Shepherds"

(a late work, 1650), now in the Louvre; the "Martyrdom of St Bartholomew" in the Prado;

and the "Pieta" in the sacristy of San Martino, Naples. His mythological

subjects are often as violent as his martyrdoms: for example, "Apollo

and Marsyas", with versions in Brussels and Naples, or the "Tityus" in the Prado . The Prado and Louvre contain numbers of his paintings; the National Gallery, London,

three. He executed several fine male portraits and a self portrait. He

was an important etcher, the most significant Spanish printmaker before Goya, producing about forty prints, nearly all in the 1620s.

Francisco de Zurbarán (baptized November 7, 1598; died August 27, 1664) was a Spanish painter. He is known primarily for his religious paintings depicting monks, nuns and martyrs, and for his still lifes. Zurbarán gained the nickname Spanish Caravaggio, owing to the forceful, realistic use of chiaroscuro in which he excelled.

Zurbarán was born in 1598 in Fuente de Cantos, Extremadura; he was baptized on November 7 of that year. His parents were Luis de Zurbarán, a haberdasher, and his wife, Isabel Márquez. In childhood he set about imitating objects with charcoal. In 1614 his father sent him to Seville to apprentice for three years with Pedro Díaz de Villanueva, an artist of whom very little is known.

While in Seville, Zurbarán married Leonor de Jordera, by whom

he had several children. Towards 1630 he was appointed painter to Philip IV,

and there is a story that on one occasion the sovereign laid his hand

on the artist's shoulder, saying "Painter to the king, king of

painters." After 1640 his austere, harsh, hard edged style was

unfavorably compared to the sentimental religiosity of Murillo and Zurbarán's reputation declined. It was only in 1658, late in Zurbarán's life that he moved to Madrid in search of work and renewed his contact with Velázquez. Zurbarán died in poverty and obscurity.

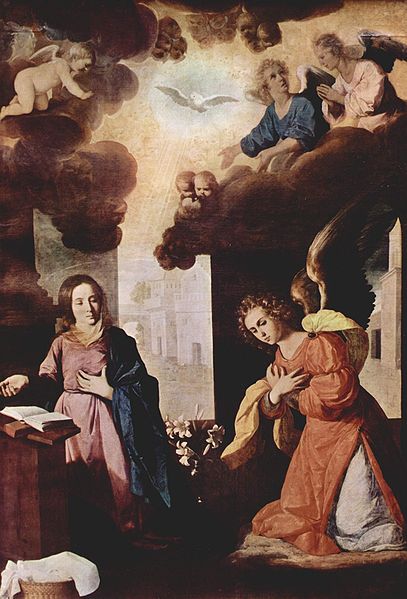

It is unknown whether Zurbarán had the opportunity to copy the paintings of Caravaggio; at any rate, he adopted Caravaggio's realistic use of chiaroscuro and tenebrism. The painter who may have had the greatest influence on his characteristically severe compositions was Juan Sánchez Cotán. Polychrome sculpture — which by the time of Zurbarán's apprenticeship had reached a level of sophistication in Seville that surpassed that of the local painters — provided another important stylistic model for the young artist; the work of Juan Martínez Montañés is especially close to Zurbarán's in spirit.

He painted directly from nature, and he made great use of the

lay figure in the study of draperies, in which he was particularly

proficient. He had a special gift for white draperies; as a consequence,

the houses of the white - robed Carthusians

are abundant in his paintings. To these rigid methods, Zurbarán

is said

to have adhered throughout his career, which was prosperous, wholly

confined to Spain, and varied by few incidents beyond those of his daily

labor. His subjects were mostly severe and ascetic religious vigils,

the spirit chastising the flesh into subjection, the compositions often

reduced to a single figure. The style is more reserved and chastened

than Caravaggio's, the tone of color often quite bluish. Exceptional

effects are attained by the precisely finished foregrounds, massed out

largely in light and shade.

In 1627 he painted the great altarpiece of St. Thomas Aquinas, now in the Museum of Fine Arts of Seville; it was executed for the church of the college of that saint there. This is Zurbarán's largest composition, containing figures of Christ, the Madonna, various saints, Charles V with knights, and Archbishop Deza (founder of the college) with monks and servitors, all the principal personages being more than life - size. It had been preceded by numerous pictures of the screen of St. Peter Nolasco in the cathedral.

In Santa Maria de Guadalupe he painted various large pictures, eight of which relate to the history of St. Jerome; and in the church of Saint Paul, Seville, a famous figure of the Crucified Savior, in grisaille, creating an illusion of marble. In 1633 he finished the paintings of the high altar of the Carthusians in Jerez. In the palace of Buenretiro, Madrid, are four large canvases representing the Labors of Hercules, an unusual instance of non - Christian subjects from the hand of Zurbarán. A fine example of his work is in the National Gallery, London: a whole length, life sized figure of a kneeling Franciscan holding a skull.

Thirteen of his paintings, depicting the patriarch Jacob and 12 of his sons, are held at Auckland Castle in Bishop Auckland. They were purchased by the Bishop of Durham, Richard Trevor, in 1756. Held by the Church of England for over 250 years, they were sold along with the castle in 2011 to philanthropist Jonathan Ruffer, who is currently exploring ways of developing them as a visitor attraction.

His principal pupils were Bernabe de Ayala and the Polanco brothers.