<Back to Index>

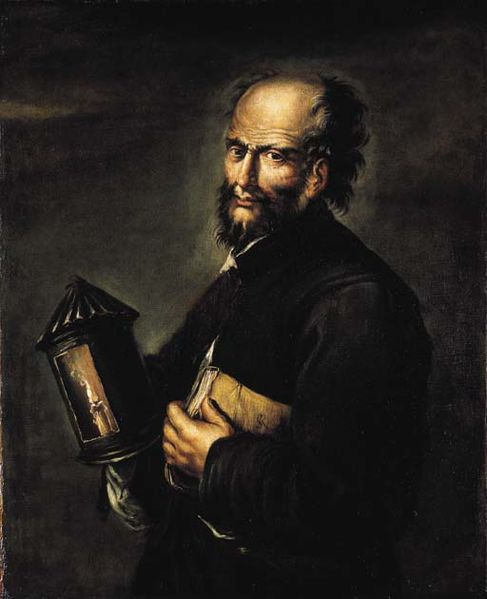

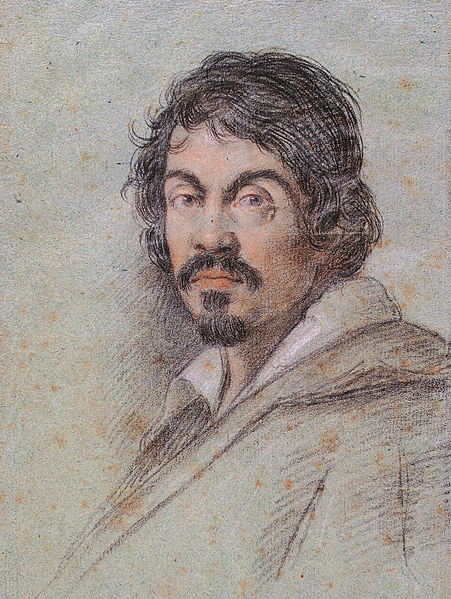

- Painter Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1571

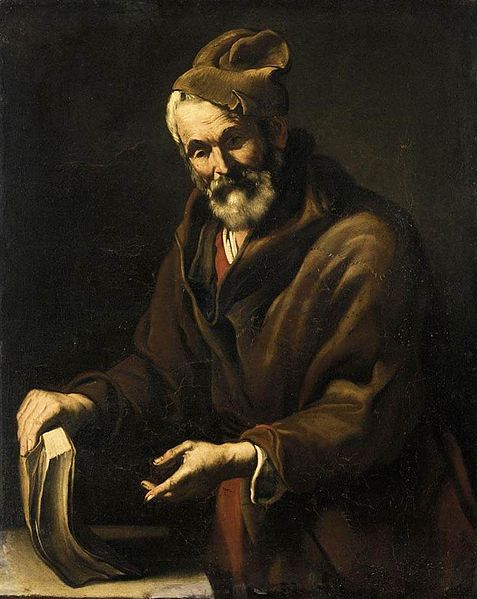

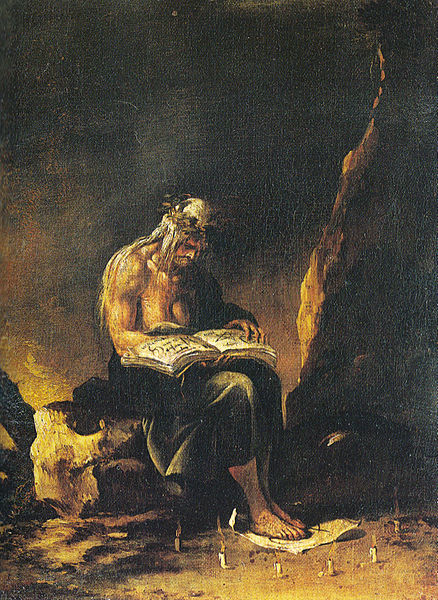

- Painter Salvator Rosa, 1615

PAGE SPONSOR

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (29 September 1571 – 18 July 1610) was an Italian artist active in Rome, Naples, Malta and Sicily between 1593 and 1610. His paintings, which combine a realistic observation of the human state, both physical and emotional, with a dramatic use of lighting, had a formative influence on the Baroque school of painting.

Caravaggio trained as a painter in Milan under a master who had himself trained under Titian. In his early twenties Caravaggio moved to Rome where, during the late 16th and early 17th centuries, many huge new churches and palazzi were being built and paintings were needed to fill them. During the Counter Reformation the Roman Catholic Church searched for religious art with which to counter the threat of Protestantism, and for this task the artificial conventions of Mannerism, which had ruled art for almost a century, no longer seemed adequate. Caravaggio's novelty was a radical naturalism that combined close physical observation with a dramatic, even theatrical, use of chiaroscuro. This came to be known as Tenebrism, the shift from light to dark with little intermediate value. He burst upon the Rome art scene in 1600 with the success of his first public commissions, the Martyrdom of Saint Matthew and Calling of Saint Matthew. Thereafter he never lacked commissions or patrons, yet he handled his success atrociously. He was jailed on several occasions, vandalized his own apartment, and ultimately had a death warrant issued for him by the Pope. An early published notice on him, dating from 1604 and describing his lifestyle three years previously, tells how "after a fortnight's work he will swagger about for a month or two with a sword at his side and a servant following him, from one ball court to the next, ever ready to engage in a fight or an argument, so that it is most awkward to get along with him." In 1606 he killed a young man in a brawl and fled from Rome with a price on his head. He was involved in a brawl in Malta in 1608, and another in Naples in 1609, possibly a deliberate attempt on his life by unidentified enemies. This encounter left him severely injured. A year later, at the age of 38, he died of a fever in Porto Ercole, near Grosseto in Tuscany, while on his way to Rome to receive a pardon.

Infamous while he lived, Caravaggio was forgotten almost immediately

after his death, and it was only in the 20th century that his importance

to the development of Western art was rediscovered. Despite this, his

influence on the new Baroque style that eventually emerged from the

ruins of Mannerism was profound. It can be seen directly or indirectly in the work of Rubens, Jusepe de Ribera, Bernini,

and Rembrandt,

and artists in the following generation heavily under his influence

were called the "Caravaggisti" or "Caravagesques", as well as Tenebrists

or "Tenebrosi" ("shadowists"). Andre Berne - Joffroy, Paul Valéry's

secretary, said of him: "What begins in the work of Caravaggio is, quite

simply, modern painting."

Caravaggio was born in Milan, where his father, Fermo Merisi, was a household administrator and architect decorator to the Marchese of Caravaggio, a town not far from the city of Bergamo. His mother, Lucia Aratori, came from a propertied family of the same district. In 1576 the family moved to Caravaggio to escape a plague which ravaged Milan, and Caravaggio's father died there in 1577. It is assumed that the artist grew up in Caravaggio, but his family kept up connections with the Sforzas and with the powerful Colonna family, who were allied by marriage with the Sforzas and destined to play a major role later in Caravaggio's life.

Caravaggio's mother died in 1584, the same year he began his four year apprenticeship to the Milanese painter Simone Peterzano, described in the contract of apprenticeship as a pupil of Titian. Caravaggio appears to have stayed in the Milan - Caravaggio area after his apprenticeship ended, but it is possible that he visited Venice and saw the works of Giorgione, whom Federico Zuccari later accused him of imitating, and Titian. He would also have become familiar with the art treasures of Milan, including Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper, and with the regional Lombard art, a style which valued simplicity and attention to naturalistic detail and was closer to the naturalism of Germany than to the stylised formality and grandeur of Roman Mannerism.

Caravaggio left Milan for Rome in mid 1592, in flight after "certain quarrels" and the wounding of a police officer. He arrived in Rome "naked and extremely needy ... without fixed address and without provision ... short of money." A few months later he was performing hack work for the highly successful Giuseppe Cesari, Pope Clement VIII's favourite artist, "painting flowers and fruit" in his factory - like workshop. Known works from this period include a small Boy Peeling a Fruit (his earliest known painting), a Boy with a Basket of Fruit, and the Young Sick Bacchus, supposedly a self portrait done during convalescence from a serious illness that ended his employment with Cesari. All three demonstrate the physical particularity for which Caravaggio was to become renowned: the fruit basket boy's produce has been analyzed by a professor of horticulture, who was able to identify individual cultivars right down to "... a large fig leaf with a prominent fungal scorch lesion resembling anthracnose (Glomerella cingulata)."

Caravaggio left Cesari in January 1594, determined to make his own way.

At this point he forged some extremely important friendships, with the

painter Prospero Orsi, the architect Onorio

Longhi, and the sixteen year old Sicilian artist Mario Minniti. Orsi,

established in the profession, introduced him to influential

collectors; Longhi, more balefully, introduced him to the world of Roman

street brawls; and Minniti served as a model and, years later, would be

instrumental in helping Caravaggio to important commissions in Sicily. The Fortune Teller,

his first composition with more than one figure, shows Mario being

cheated by a gypsy girl. The theme was quite new for Rome, and proved

immensely influential over the next century and beyond. This, however,

was in the future: at the time, Caravaggio sold it for practically

nothing. The Cardsharps — showing another naive youth of privilege falling the victim of card

cheats — is even more psychologically complex, and perhaps Caravaggio's

first true masterpiece. Like the Fortune Teller it was immensely

popular, and over 50 copies survive. More importantly, it attracted the

patronage of Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte,

one of the leading connoisseurs in Rome. For Del Monte and his wealthy

art loving circle Caravaggio executed a number of intimate

chamber pieces — The Musicians, The Lute Player, a tipsy Bacchus, an allegorical but realistic Boy Bitten by a Lizard — featuring Minniti and other adolescent models.

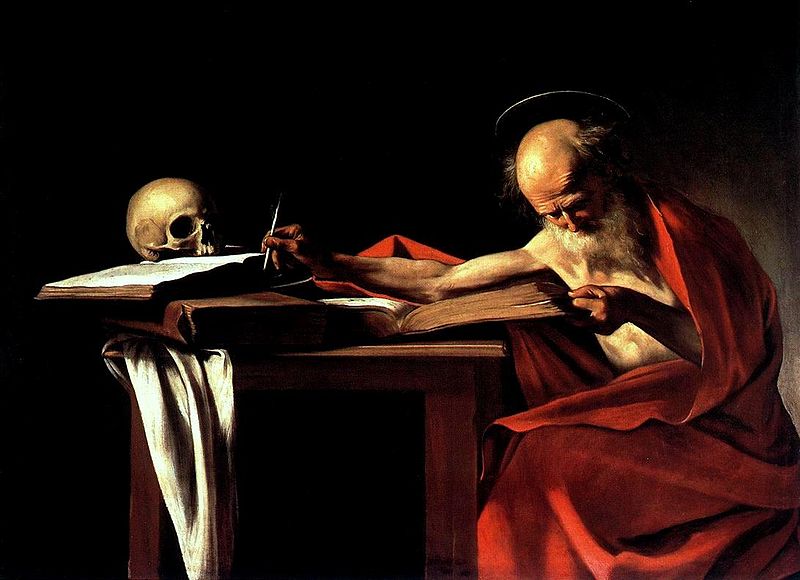

The realism returned with Caravaggio's first paintings on religious themes, and the emergence of remarkable spirituality. The first of these was the Penitent Magdalene, showing Mary Magdalene at the moment when she has turned from her life as a courtesan and sits weeping on the floor, her jewels scattered around her. "It seemed not a religious painting at all ... a girl sitting on a low wooden stool drying her hair ... Where was the repentance ... suffering ... promise of salvation?" It was understated, in the Lombard manner, not histrionic in the Roman manner of the time. It was followed by others in the same style: Saint Catherine, Martha and Mary Magdalene, Judith Beheading Holofernes, a Sacrifice of Isaac, a Saint Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy, and a Rest on the Flight into Egypt. The works, while viewed by a comparatively limited circle, increased Caravaggio's fame with both connoisseurs and his fellow artists. But a true reputation would depend on public commissions, and for these it was necessary to look to the Church.

Already evident was the intense realism or naturalism for which

Caravaggio is now famous. He preferred to paint his subjects as the eye

sees them, with all their natural flaws and defects instead of as

idealized creations. This allowed a full display of Caravaggio's

virtuosic talents. This shift from accepted standard practice and the

classical idealism of Michelangelo was very controversial at the time. Not only was his realism a

noteworthy feature of his paintings during this period, he turned away

from the lengthy preparations traditional in central Italy at the time.

Instead, he preferred the Venetian practice of working in oils directly

from the subject - half length figures and still life. One of the

characteristic paintings by Caravaggio at this time which gives a good

demonstration of his virtuoso talent was his work, Supper at Emmaus from c.1600 – 1601.

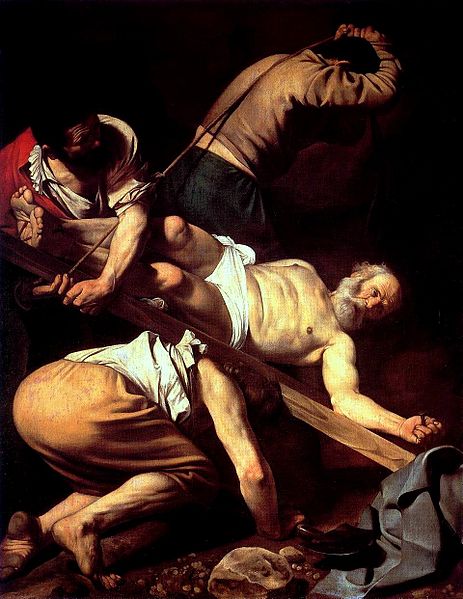

In 1599, presumably through the influence of Del Monte, Caravaggio was contracted to decorate the Contarelli Chapel in the church of San Luigi dei Francesi. The two works making up the commission, the Martyrdom of Saint Matthew and Calling of Saint Matthew, delivered in 1600, were an immediate sensation. Caravaggio's tenebrism (a heightened chiaroscuro) brought high drama to his subjects, while his acutely observed realism brought a new level of emotional intensity. Opinion among Caravaggio's artist peers was polarized. Some denounced him for various perceived failings, notably his insistence on painting from life, without drawings, but for the most part he was hailed as a great artistic visionary: "The painters then in Rome were greatly taken by this novelty, and the young ones particularly gathered around him, praised him as the unique imitator of nature, and looked on his work as miracles."

Caravaggio went on to secure a string of prestigious commissions for religious works featuring violent struggles, grotesque decapitations, torture and death, most notable and most technically masterful among them The Taking of Christ of circa 1602 for the Mattei Family, recently rediscovered in Ireland after two centuries. For the most part each new painting increased his fame, but a few were rejected by the various bodies for whom they were intended, at least in their original forms, and had to be re-painted or find new buyers. The essence of the problem was that while Caravaggio's dramatic intensity was appreciated, his realism was seen by some as unacceptably vulgar. His first version of Saint Matthew and the Angel, featured the saint as a bald peasant with dirty legs attended by a lightly clad over - familiar boy angel, was rejected and a second version had to be painted as The Inspiration of Saint Matthew. Similarly, The Conversion of Saint Paul was rejected, and while another version of the same subject, the Conversion on the Way to Damascus, was accepted, it featured the saint's horse's haunches far more prominently than the saint himself, prompting this exchange between the artist and an exasperated official of Santa Maria del Popolo: "Why have you put a horse in the middle, and Saint Paul on the ground?" "Because!" "Is the horse God?" "No, but he stands in God's light!"

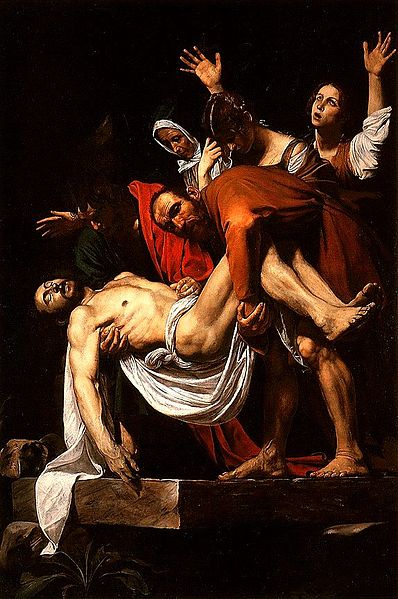

Other works included Entombment, the Madonna di Loreto (Madonna of the Pilgrims), the Grooms' Madonna, and the Death of the Virgin. The history of these last two paintings illustrate the reception given to some of Caravaggio's art, and the times in which he lived. The Grooms' Madonna, also known as Madonna dei palafrenieri, painted for a small altar in Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome, remained there for just two days, and was then taken off. A cardinal's secretary wrote: "In this painting there are but vulgarity, sacrilege, impiousness and disgust... One would say it is a work made by a painter that can paint well, but of a dark spirit, and who has been for a lot of time far from God, from His adoration, and from any good thought..." The Death of the Virgin, then, commissioned in 1601 by a wealthy jurist for his private chapel in the new Carmelite church of Santa Maria della Scala, was rejected by the Carmelites in 1606. Caravaggio's contemporary Giulio Mancini records that it was rejected because Caravaggio had used a well known prostitute as his model for the Virgin; Giovanni Baglione, another contemporary, tells us it was due to Mary's bare legs — a matter of decorum in either case. Caravaggio scholar John Gash suggests that the problem for the Carmelites may have been theological rather than aesthetic, in that Caravaggio's version fails to assert the doctrine of the Assumption of Mary, the idea that the Mother of God did not die in any ordinary sense but was assumed into Heaven. The replacement altarpiece commissioned (from one of Caravaggio's most able followers, Carlo Saraceni), showed the Virgin not dead, as Caravaggio had painted her, but seated and dying; and even this was rejected, and replaced with a work which showed the Virgin not dying, but ascending into Heaven with choirs of angels. In any case, the rejection did not mean that Caravaggio or his paintings were out of favor. The Death of the Virgin was no sooner taken out of the church than it was purchased by the Duke of Mantua, on the advice of Rubens, and later acquired by Charles I of England before entering the French royal collection in 1671.

One secular piece from these years is Amor Victorious, painted in 1602 for Vincenzo Giustiniani,

a member of Del Monte's circle. The model was named in a memoir of the

early 17th century as "Cecco", the diminutive for Francesco. He is

possibly Francesco Boneri, identified with an artist active in the

period 1610 – 1625 and known as Cecco del Caravaggio ('Caravaggio's Cecco'),

carrying a bow and arrows and trampling symbols of the warlike and

peaceful arts and sciences underfoot. He is unclothed, and it is

difficult to accept this grinning urchin as the Roman god Cupid

– as difficult as it was to accept Caravaggio's other semi - clad

adolescents as the various angels he painted in his canvases, wearing

much the same stage - prop wings. The point, however, is the intense yet

ambiguous reality of the work: it is simultaneously Cupid and Cecco, as

Caravaggio's Virgins were simultaneously the Mother of Christ and the

Roman courtesans who modeled for them.

Caravaggio led a tumultuous life. He was notorious for brawling, even in a time and place when such behavior was commonplace, and the transcripts of his police records and trial proceedings fill several pages. On 29 May 1606, he killed, possibly unintentionally, a young man named Ranuccio Tomassoni from Terni (Umbria). Previously his high placed patrons had protected him from the consequences of his escapades, but this time they could do nothing. Caravaggio, outlawed, fled to Naples. There, outside the jurisdiction of the Roman authorities and protected by the Colonna family, the most famous painter in Rome became the most famous in Naples. His connections with the Colonnas led to a stream of important church commissions, including the Madonna of the Rosary, and The Seven Works of Mercy.

Despite his success in Naples, after only a few months in the city Caravaggio left for Malta, the headquarters of the Knights of Malta, presumably hoping that the patronage of Alof de Wignacourt, Grand Master of the Knights, could help him secure a pardon for Tomassoni's death. De Wignacourt proved so impressed at having the famous artist as official painter to the Order that he inducted him as a knight, and the early biographer Bellori records that the artist was well pleased with his success. Major works from his Malta period include a huge Beheading of Saint John the Baptist (the only painting to which he put his signature) and a Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt and his Page, as well as portraits of other leading knights. Yet by late August 1608 he was arrested and imprisoned. The circumstances surrounding this abrupt change of fortune have long been a matter of speculation, but recent investigation has revealed it to have been the result of yet another brawl, during which the door of a house was battered down and a knight seriously wounded. He was imprisoned by the knights and managed to escape. By December he had been expelled from the Order "as a foul and rotten member."

Caravaggio made his way to Sicily where he met his old friend Mario Minniti, who was now married and living in Syracuse.

Together they set off on what amounted to a triumphal tour from

Syracuse to Messina and on to the island capital, Palermo. In each city

Caravaggio continued to win prestigious and well paid commissions. Among

other works from this period are Burial of St. Lucy, The Raising of Lazarus, and Adoration of the Shepherds.

His style continued to evolve, showing now friezes of figures isolated

against vast empty backgrounds. "His great Sicilian altarpieces isolate

their shadowy, pitifully poor figures in vast areas of darkness; they

suggest the desperate fears and frailty of man, and at the same time

convey, with a new yet desolate tenderness, the beauty of humility and

of the meek, who shall inherit the earth."

Contemporary reports depict a man whose behavior was becoming

increasingly bizarre, sleeping fully armed and in his clothes, ripping

up a painting at a slight word of criticism, mocking the local painters.

After only nine months in Sicily, Caravaggio returned to Naples. According to his earliest biographer he was being pursued by enemies while in Sicily and felt it safest to place himself under the protection of the Colonnas until he could secure his pardon from the pope (now Paul V) and return to Rome. In Naples he painted The Denial of Saint Peter, a final John the Baptist (Borghese), and his last picture, The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula. His style continued to evolve — Saint Ursula is caught in a moment of highest action and drama, as the arrow fired by the king of the Huns strikes her in the breast, unlike earlier paintings which had all the immobility of the posed models. The brushwork was much freer and more impressionistic. Had Caravaggio lived, something new would have come.

In Naples an attempt was made on his life, by persons unknown. At first it was reported in Rome that the "famous artist" Caravaggio was dead, but then it was learned that he was alive, but seriously disfigured in the face. He painted a Salome with the Head of John the Baptist (Madrid), showing his own head on a platter, and sent it to de Wignacourt as a plea for forgiveness. Perhaps at this time he painted also a David with the Head of Goliath, showing the young David with a strangely sorrowful expression gazing on the severed head of the giant, which is again Caravaggio's. This painting he may have sent to his patron the unscrupulous art loving Cardinal Scipione Borghese, nephew of the pope, who had the power to grant or withhold pardons.

In the summer of 1610 he took a boat northwards to receive the pardon, which seemed imminent thanks to his powerful Roman friends. With him were three last paintings, gifts for Cardinal Scipione. What happened next is the subject of much confusion and conjecture. The bare facts are that on 28 July an anonymous avviso (private newsletter) from Rome to the ducal court of Urbino reported that Caravaggio was dead. Three days later another avviso said that he had died of fever on his way from Naples to Rome. A poet friend of the artist later gave 18 July as the date of death, and a recent researcher claims to have discovered a death notice showing that the artist died on that day of a fever in Porto Ercole, near Grosseto in Tuscany. Human remains found in a church in Porto Ercole in 2010 are believed to almost certainly belong to Caravaggio. The findings come after a year long investigation using DNA, carbon dating and other analyses.

Caravaggio might have died of lead poisoning. Bones with high lead levels were recently found in a grave likely to be Caravaggio's. Paints used at the time contained high amounts of lead salts. Caravaggio is known to have indulged in violent behavior, as caused by lead poisoning.

Caravaggio "put the oscuro (shadows) into chiaroscuro." Chiaroscuro was practiced long before he came on the scene, but it was Caravaggio who made the technique definitive, darkening the shadows and transfixing the subject in a blinding shaft of light. With this came the acute observation of physical and psychological reality which formed the ground both for his immense popularity and for his frequent problems with his religious commissions. He worked at great speed, from live models, scoring basic guides directly onto the canvas with the end of the brush handle; very few of Caravaggio's drawings appear to have survived, and it is likely that he preferred to work directly on the canvas. The approach was anathema to the skilled artists of his day, who decried his refusal to work from drawings and to idealize his figures. Yet the models were basic to his realism. Some have been identified, including Mario Minniti and Francesco Boneri, both fellow artists, Mario appearing as various figures in the early secular works, the young Francesco as a succession of angels, Baptists and Davids in the later canvasses. His female models include Fillide Melandroni, Anna Bianchini, and Maddalena Antognetti (the "Lena" mentioned in court documents of the "artichoke" case as Caravaggio's concubine), all well known prostitutes, who appear as female religious figures including the Virgin and various saints. Caravaggio himself appears in several paintings, his final self portrait being as the witness on the far right to the Martyrdom of Saint Ursula.

Caravaggio had a noteworthy ability to express in one scene of unsurpassed vividness the passing of a crucial moment. The Supper at Emmaus

depicts the recognition of Christ by his disciples: a moment before he

is a fellow traveler, mourning the passing of the Messiah, as he never

ceases to be to the inn - keeper's eyes, the second after, he is the

Savior. In The Calling of St Matthew,

the hand of the Saint points to himself as if he were saying "who,

me?", while his eyes, fixed upon the figure of Christ, have already

said, "Yes, I will follow you". With The Resurrection of Lazarus,

he goes a step further, giving us a glimpse of the actual physical

process of resurrection. The body of Lazarus is still in the throes of

rigor mortis, but his hand, facing and recognizing that of Christ, is

alive. Other major Baroque artists would travel the same path, for

example Bernini, fascinated with themes from Ovid's Metamorphoses.

The installation of the St. Matthew paintings in the Contarelli Chapel had an immediate impact among the younger artists in Rome, and Caravaggism became the cutting edge for every ambitious young painter. The first Caravaggisti included Orazio Gentileschi and Giovanni Baglione. Baglione's Caravaggio phase was short lived; Caravaggio later accused him of plagiarism and the two were involved in a long feud. Baglione went on to write the first biography of Caravaggio. In the next generation of Caravaggisti there were Carlo Saraceni, Bartolomeo Manfredi and Orazio Borgianni. Gentileschi, despite being considerably older, was the only one of these artists to live much beyond 1620, and ended up as court painter to Charles I of England. His daughter Artemisia Gentileschi was also close to Caravaggio, and one of the most gifted of the movement. Yet in Rome and in Italy it was not Caravaggio, but the influence of Annibale Carracci, blending elements from the High Renaissance and Lombard realism, which ultimately triumphed.

Caravaggio's brief stay in Naples produced a notable school of Neapolitan Caravaggisti, including Battistello Caracciolo and Carlo Sellitto. The Caravaggisti movement there ended with a terrible outbreak of plague in 1656, but the Spanish connection – Naples was a possession of Spain – was instrumental in forming the important Spanish branch of his influence.

A group of Catholic artists from Utrecht, the "Utrecht Caravaggisti",

traveled to Rome as students in the first years of the 17th century

and were profoundly influenced by the work of Caravaggio, as Bellori

describes. On their return to the north this trend had a short lived but

influential flowering in the 1620s among painters like Hendrick ter Brugghen, Gerrit van Honthorst,

Andries Both and Dirck van Baburen. In the following generation the

effects of Caravaggio, although attenuated, are to be seen in the work

of Rubens (who purchased one of his paintings for the Gonzaga of Mantua

and painted a copy of the Entombment of Christ), Vermeer, Rembrandt, and Velázquez, the last of whom presumably saw his work during his various sojourns in Italy.

Caravaggio's fame scarcely survived his death. His innovations inspired the Baroque, but the Baroque took the drama of his chiaroscuro without the psychological realism. While he directly influenced the style of the artists mentioned above, and, at a distance, the Frenchmen Georges de La Tour and Simon Vouet, and the Spaniard Giuseppe Ribera, within a few decades his works were being ascribed to less scandalous artists, or simply overlooked. The Baroque, to which he contributed so much, had evolved, and fashions had changed, but perhaps more pertinently Caravaggio never established a workshop as the Carracci's did, and thus had no school to spread his techniques. Nor did he ever set out his underlying philosophical approach to art, the psychological realism which can only be deduced from his surviving work. Thus his reputation was doubly vulnerable to the critical demolition jobs, done by two of his earliest biographers, Giovanni Baglione, a rival painter with a personal vendetta, and the influential 17th century critic Giovan Bellori, who had not known him but was under the influence of the French Classicist Poussin, who had not known him either but hated his work.

In the 1920s art critic Roberto Longhi brought Caravaggio's name once

more to the foreground, and placed him in the European tradition:

"Ribera, Vermeer, La Tour and Rembrandt

could never have existed without him. And the art of Delacroix, Courbet

and Manet would have been utterly different". The influential Bernard

Berenson agreed: "With the exception of Michelangelo, no other Italian

painter exercised so great an influence."

Caravaggio's epitaph was composed by his friend Marzio Milesi. It reads:

"Michelangelo Merisi, son of Fermo di Caravaggio - in painting not equal to a painter, but to Nature itself - died in Port' Ercole - betaking himself hither from Naples - returning to Rome - 15th calend of August - In the year of our Lord 1610 - He lived thirty - six years nine months and twenty days - Marzio Milesi, Jurisconsult - Dedicated this to a friend of extraordinary genius."

Salvator Rosa (1615 – March 15, 1673) was an Italian Baroque painter, poet and printmaker, active in Naples, Rome and Florence. As a painter, he is best known as an "unorthodox and extravagant" and a "perpetual rebel" proto - Romantic.

He was born in Arenella, in the outskirts of Naples, on either June 20 or July 21, 1615. His father, Vito Antonio de Rosa, a land surveyor, urged his son to become a lawyer or a priest, and entered him into the convent of the Somaschi fathers. Yet Salvator showed a preference for the arts, and secretly worked with his maternal uncle Paolo Greco to learn about painting. He soon transferred himself to the tutelage of his brother - in - law Francesco Francanzano, a pupil of Ribera, and afterwards to either Aniello Falcone, a contemporary of Domenico Gargiulo, or Ribera himself. Some sources claim he spent time living with roving bandits. At the age of seventeen he lost his father; his mother was destitute with at least five children, and Salvator found himself without financial support.

He continued apprenticeship with Falcone, helping him complete his battlepiece canvases. In that studio, it is said that Lanfranco took notice of his work, and advised him to relocate to Rome, where he stayed from 1634 – 36.

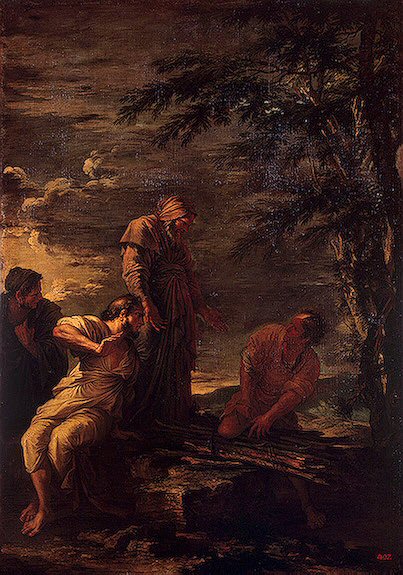

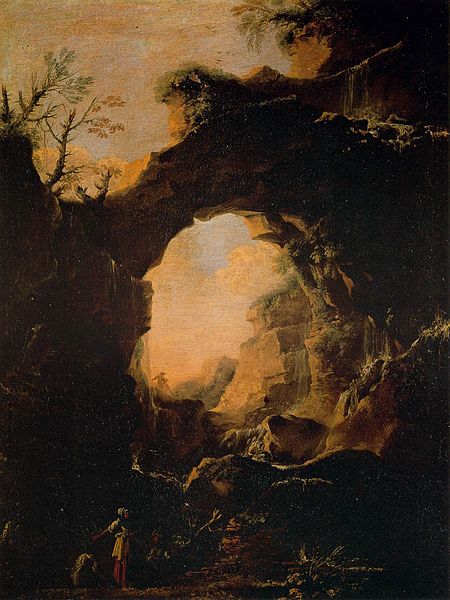

Returning to Naples, he began painting haunting landscapes, overgrown with vegetation, or jagged beaches, mountains, and caves. Rosa was among the first to paint "romantic" landscapes, with a special turn for scenes of picturesque often turbulent and rugged scenes peopled with shepherds, brigands, seamen, soldiers. These early landscapes were sold cheaply through private dealers.

He returned to Rome in 1638 – 39, where he was housed by Cardinal Francesco Maria Brancaccio, bishop of Viterbo. For the Chiesa Santa Maria della Morte in Viterbo, Rosa painted his first and one of his few altarpieces with an Incredulity of Thomas.

While Rosa had a facile genius at painting, he pursued a wide variety

of arts: music, poetry, writing, etching and acting. In Rome, he

befriended Pietro Testa and Claude Lorraine.

During a Roman carnival play he wrote and acted in a masque, in which

his character bustled about Rome distributing satirical prescriptions

for diseases of the body and more particularly of the mind. In costume,

he inveighed against the farcical comedies acted in the Trastevere under

the direction of Bernini.

While his plays were successful, this also gained him powerful enemies

among patrons and artists, including Bernini himself, in Rome. By late

1639, he had to relocate to Florence, where he stayed for 8 years. He

had been in part, invited by a Cardinal Giancarlo de Medici. Once there, Rosa sponsored a combination of studio and salon of poets, playwrights, and painters — the so called Accademia dei Percossi

("Academy of the Stricken"). To the rigid art milieu of Florence, he

introduced his canvases of wild landscapes; while influential, he

gathered few true pupils. Another painter poet, Lorenzo Lippi, shared

with Rosa the hospitality of the cardinal and the same circle of

friends. Lippi encouraged him to proceed with the poem Il Malmantile Racquistato. He was well acquainted also with Ugo and Giulio Maffei, and housed with them in Volterra, where he wrote four satires Music, Poetry, Painting and War. About the same time he painted his own portrait, now in the National Gallery, London.

In 1646 he returned to Naples, and appears to have sympathized with the 1648 insurrection of Masaniello, as a passage in one of his satires suggests. His actual participation in the revolt is dubious. It is alleged that Rosa, along with other painters — Coppola, Paolo Porpora, Domenico Gargiulo, Pietro dal Po, Marzio Masturzo, the two Vaccari and Cadogna — all under the captaincy of Aniello Falcone, formed the Compagnia della Morte, whose mission it was to hunt down Spaniards in the streets, not sparing even those who had sought religious asylum. He painted a portrait of Masaniello — probably from reminiscence rather than life. On the approach of Don Juan de Austria, the blood - stained Compagnia dispersed.

Other tales recount that from there he escaped and joined with brigands in the Abruzzi. Although this incident cannot be conveniently dovetailed into known dates of his career, in 1846 a famous romantic ballet about this story titled Catarina was produced in London by the choreographer Jules Perrot and composer Cesare Pugni.

He returned to stay in Rome in 1649. Here he increasingly focused on

large scale paintings, tackling themes and stories unusual for

seventeenth century painters. These included Democritus amid the Tombs, The Death of Socrates, Regulus in the Spiked Cask (these two are now in England), Justice Quitting the Earth and the Wheel of Fortune.

This last work, with its implication that too often foolish artists

received rewards that did not match their talent, raised a storm of

controversy. Rosa, endeavoring at conciliation, published a description

of its meaning (probably softened down not a little from the real

facts); nonetheless he was nearly arrested. It was about this time that

Rosa wrote his satire named Babylon.

His criticisms of Roman art culture won him several enemies. An allegation arose that his published satires were not his own, but stolen. Rosa indignantly denied the charges, but one must admit that the satires deal so extensively and with such ready manipulation of classical names, allusions and anecdotes, that one is rather at a loss to fix upon the period of his busy career at which Rosa could possibly have imbued his mind with such a multitude of semi - erudite details. It may perhaps be legitimate to assume literary friends in Florence and Volterra coached him about the topic of his satires, the compositions of which remained nonetheless his own. To confute his detractors he now wrote the last of the series, entitled Envy.

Among the pictures of his last years were the admired Battlepiece and Saul and the Witch of Endor (latter perhaps final work) now in Louvre, painted in 40 days, full of longdrawn carnage, with ships burning in the offing; Pythagoras and the Fishermen; and the Oath of Catiline (Pitti Palace).

While occupied with a series of satirical portraits, to be closed by one of himself, Rosa was assailed by dropsy. He died a half year later. In his last moments he married a Florentine named Lucrezia, who had borne him two sons, one of them surviving him, and he died in a contrite frame of mind. He lies buried in Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri, where a portrait of him has been set up. Salvator Rosa, after struggles of his early youth, had successfully earned a handsome fortune.

He was a significant etcher, with a highly popular and influential series of small prints of soldiers, and a number of larger and very ambitious subjects.

Rosa's most lasting influence was on the later development of romantic and picturesque traditions within painting. As Wittkower states, it is in his landscapes, not his grand historical or religious dramas, that Rosa truly expresses his innovative abilities most graphically. Rosa himself may have dismissed them as frivolous cappricci in comparison to his other themes, but these academically conventional canvases often restrained his rebellious streak. In general, in landscapes he avoided the idyllic and pastoral calm countrysides of Claude Lorraine and Paul Brill, and created brooding, melancholic fantasies, awash in ruins and brigands. By the eighteenth century, the contrasts between Rosa and artists such as Claude was much remarked upon. A 1748 poem by James Thompson, The Castle of Indolence, illustrated this: Whate'er Lorraine light touched with softening hue/ Or savage Rosa dashed, or learned Poussin drew. He influenced Gaspar Dughet's landscape style.

A recent exhibit of Turner's work, at the Prado museum in Madrid, notes the influence Rosa had on Turner, in his landscapes. In fact it is reported that Turner consciously wanted to be associated with the work of Rosa. Another exhibition of Rosa's work, held at London's Dulwich Picture Gallery in 2010, emphasized the strangeness of Rosa's painting and themes, showing his enthusiasm for 'bandits, wilderness and magic'.

In a time when artists where often highly constrained by patrons,

Rosa had a plucky streak of independence, which celebrated the special

role of the artist. "Our wealth must consist in things of the spirit,

and in contenting ourselves with sipping, while others gorge themselves

in prosperity". He refused to paint on commission or to agree on a price

beforehand, and he chose his own subjects. He painted in order "to be

carried away by the transports of enthusiasm and use my brushes only

when I feel myself rapt". This tempestuous spirit became the darling of

British Romantics.

The satires of Salvator Rosa deserve more attention than they have generally received. There are, however, two recent books taking account of them — by Cesareo, 1892, and Cartelli, 1899. The satires, though considerably spread abroad during his lifetime, were not published until 1719. They are all in terza rima, written without much literary correctness, but remarkably spirited, pointed and even brilliant. They are slashingly denunciatory, and from this point of view too monotonous in treatment. Rosa here appears as a very severe castigator of all ranks and conditions of men, not sparing the highest, and as a champion of the poor and downtrodden, and of moral virtue and Catholic faith. It seems odd that a man who took so free a part in the pleasures and diversions of life should be so ruthless to the ministers of these.

The satire on Music exposes the insolence and profligacy of musicians, and the shame of courts and churches in encouraging them. Poetry dwells on the pedantry, imitativeness, adulation, affectation and indecency of poets — also their poverty, and the neglect with which they were treated; and there is a very vigorous sortie against oppressive governors and aristocrats. Tasso's glory is upheld; Dante is spoken of as obsolete, and Ariosto as corrupting.

Painting inveighs against the pictorial treatment of squalid subjects, such as beggars (though Rosa must surely himself have been partly responsible for this misdirection of the art), against the ignorance and lewdness of painters, and their tricks of trade, and the gross indecorum of painting sprawling half - naked saints of both sexes. War (which contains a eulogy of Masaniello) derides the folly of mercenary soldiers, who fight and perish while kings stay at home; the vile morals of kings and lords, their heresy and unbelief.

In Babylon ofrece Rosa represents himself as a fisherman, Tirreno, constantly unlucky in his net hauls on the Euphrates; he converses with a native of the country, Ergasto. Babylon (Rome) is very severely treated, and Naples much the same.

Envy (the last of the satires, and generally accounted the

best, although without strong apparent reason) represents Rosa dreaming

that, as he is about to inscribe in all modesty his name upon the

threshold of the temple of glory, the goddess or fiend of Envy obstructs

him, and a long interchange of reciprocal objurgations ensues. Here

occurs the highly charged portrait of the chief Roman detractor of

Salvator (we are not aware that he has ever been identified by name);

and the painter protests that he would never condescend to do any of the

lascivious work in painting so shamefully in vogue.

A number of biographies and fictionalizations of the life of Rosa exist:

- Domenico Passeri speaks of him in Vite de Pittori

- Salvini, Satire e Vita di Salvator Rosa

- Baldinucci

- Bernardo de' Dominici, Vita di Rosa (1742, Naples)

- In England, Lady Morgan in The Life and Times of Salvator Rosa, and Albert Cotton in A Company of Death romanticized his life.

- Rosa is also the fictional hero of the novella Signor Formica, 1819, also known simply as Salvator Rosa, by E.T.A. Hoffmann.

- Salvatore Rosa is a 19th century Italian Opera by Antônio Carlos Gomes, with libretto by Antonio Ghislanzoni, after the novel Masaniello by Eugene Mirecourt.

- The 1846 ballet Catarina by the choreographer Jules Perrot and the composer Cesare Pugni was produced in London at Her Majesty's Theatre, and was inspired by the alleged story of Rosa's dealings with Brigands of the Abruzzi.

One of the pieces included in the piano collection Années de Pèlerinage by Franz Liszt is entitled "Canzonetta del Salvator Rosa."