<Back to Index>

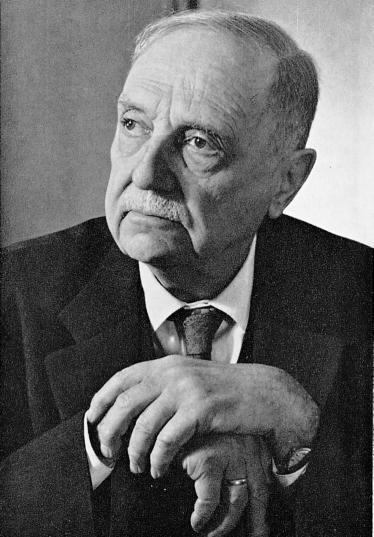

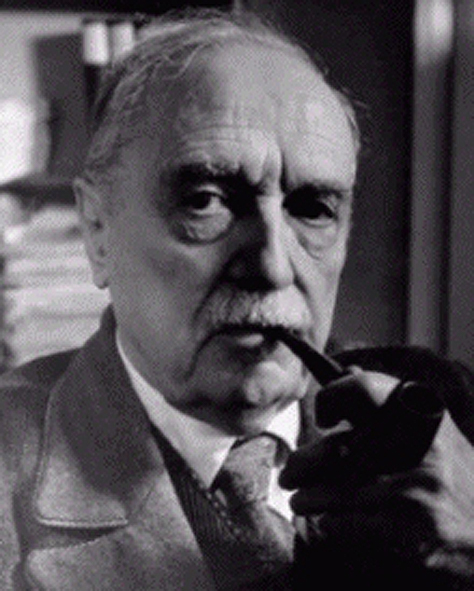

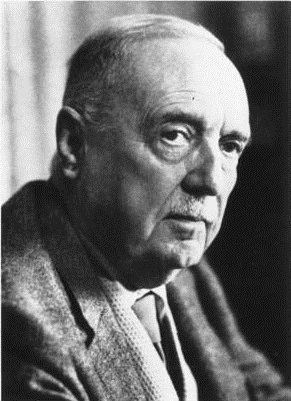

- Theologian Rudolf Karl Bultmann, 1884

PAGE SPONSOR

Rudolf Karl Bultmann (August 20, 1884, Wiefelstede – July 30, 1976, Marburg) was a German theologian of Lutheran background, who was for three decades professor of New Testament studies at the University of Marburg. He defined an almost complete split between history and faith, called demythology, writing that only the bare fact of Christ crucified was necessary for Christian faith.

Bultmann was born in Wiefelstede, Oldenburg, the son of Arthur Kennedy Bultmann, a Lutheran minister. He did his Abitur at the Altes Gymnasium in Oldenburg, and studied theology at Tübingen. After three terms, Bultmann went to the University of Berlin for two terms, and finally to Marburg for two more terms. He received his degree in 1910 from Marburg with a dissertation on the Epistles of St Paul. After submitting a Habilitation two years later, he became a lecturer on the New Testament at Marburg. After brief lectureships at Breslau and Giessen, he returned to Marburg in 1921 as a full professor, and stayed there until his retirement in 1951. From autumn 1944 until the end of World War II in 1945 he took into his family Uta Ranke - Heinemann, who had fled the bombs and destruction in Essen.

Bultmann was a student of Hermann Gunkel, Johannes Weiss, and Wilhelm Heitmüller. Hans Jonas, Ernst Käsemann, Günther Bornkamm, Hannah Arendt and Helmut Koester were among his students.

He was a member of the Confessing Church and critical towards National Socialism.

He spoke out against the mistreatment of Jews, against nationalistic

excesses and against the dismissal of non - Aryan Christian ministers.

He

did not, however, speak out against "the antiSemitic [sic] laws which

had

already been promulgated" and he was philosophically limited in his

ability to "repudiate, in a comprehensive manner, the central tenets of

Nazi racism and antiSemitism[sic]."

His History of the Synoptic Tradition (1921) is still highly regarded as an essential tool for gospel research, even by scholars who reject his analyses of the conventional rhetorical pericopes or narrative units of which the Gospels are assembled, and the historically - oriented principles called "form criticism" of which Bultmann has been the most influential exponent:

- "The aim of form - criticism is to determine the original form of a piece of narrative, a dominical saying or a parable. In the process we learn to distinguish secondary additions and forms, and these in turn lead to important results for the history of the tradition."

In 1941 he applied form criticism to the Gospel of John, in which he distinguished the presence of a lost Signs Gospel on which John, alone of the evangelists, depended. This monograph, highly controversial at the time, became a milestone in research into the historical Jesus. The same year his lecture New Testament and Mythology: The Problem of Demythologizing the New Testament Message called on interpreters to replace traditional supernaturalism with the temporal and existential categories of Bultmann's colleague, Martin Heidegger, rejecting doctrines such as the pre - existence of Christ. Bultmann believed this endeavor would make accessible to modern audiences - already immersed in science and technology - the reality of Jesus' teachings. Bultmann thus understood the project of "demythologizing the New Testament proclamation" as an evangelical task, clarifying the kerygma, or gospel proclamation, by stripping it of elements of the first century "mythical world picture" that had potential to alienate modern people from Christian faith:

"It is impossible to repristinate a past world picture by sheer resolve, especially a mythical world picture, now that all of our thinking is irrevocably formed by science. A blind acceptance of New Testament mythology would be simply arbitrariness; to make such acceptance a demand of faith would be to reduce faith to a work"

While Bultmann reinterpreted theological language in existential terms, he nonetheless maintained that the New Testament proclaimed a message more radical than any modern existentialism. In both the boasting of legalists "who are faithful to the law," and the boasting of the philosophers "who are proud of their wisdom," Bultmann finds a "basic human attitude" of "highhandedness that tries to bring within our own power even the submission that we know to be our authentic being." Standing against all human highhandedness is the New Testament, "which claims that we can in no way free ourselves from our factual fallenness in the world but are freed from it only by an act of God ... the salvation occurrence that is realized in Christ." Bultmann remained convinced the narratives of the life of Jesus were offering theology in story form. Lessons were taught in the familiar language of myth. They were not to be excluded, but given explanation so they could be understood for today. Bultmann thought faith should become a present day reality. To Bultmann, the people of the world appeared to be always in disappointment and turmoil. Faith must be a determined vital act of will, not a culling and extolling of "ancient proofs."

He carried form - criticism so far as to call the historical value of the gospels into serious question. Some

scholars criticized Bultmann and other critics for excessive skepticism

regarding the historical reliability of the gospel narratives. The full

impact of Bultmann was not felt until the English publication of Kerygma and Mythos (1948). The conservative and confessing Lutheran theologian, Walter Kunneth provided some interesting insights on Bultmann in his Die Theologie der Auferstehung.