<Back to Index>

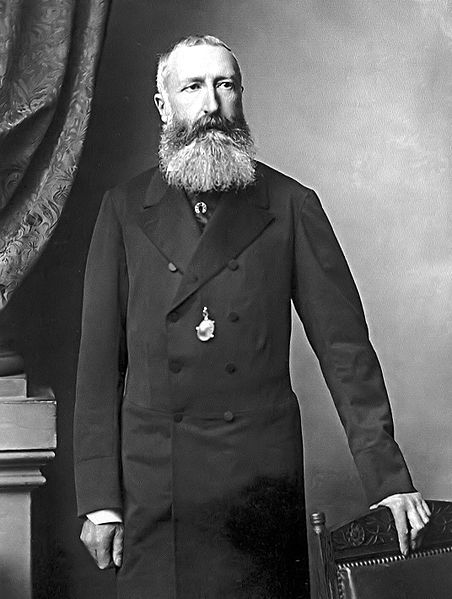

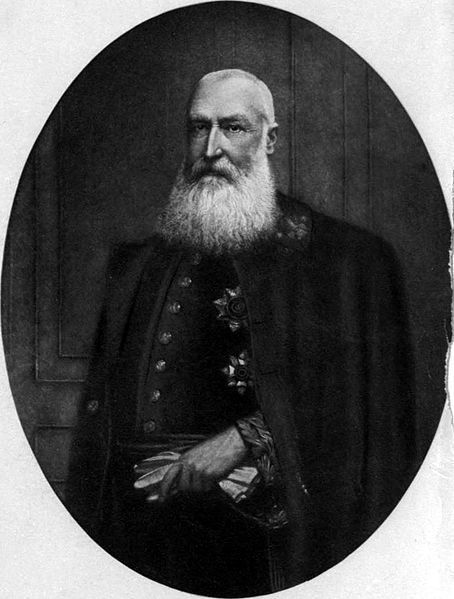

- King of the Belgians Leopold II, 1835

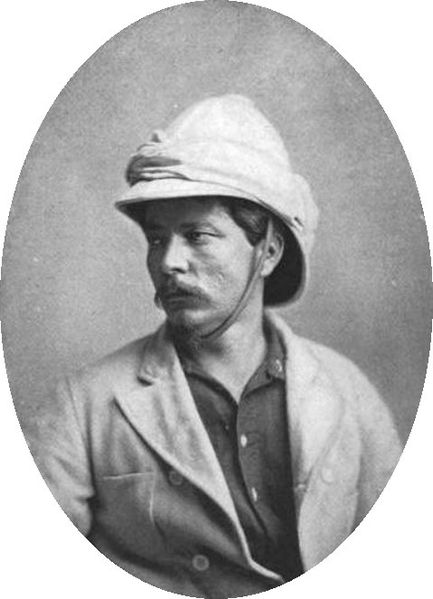

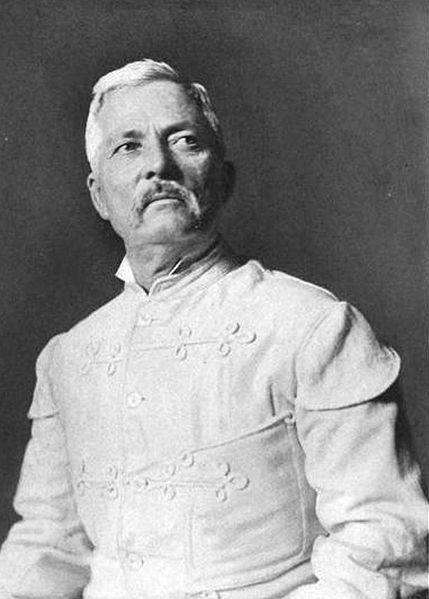

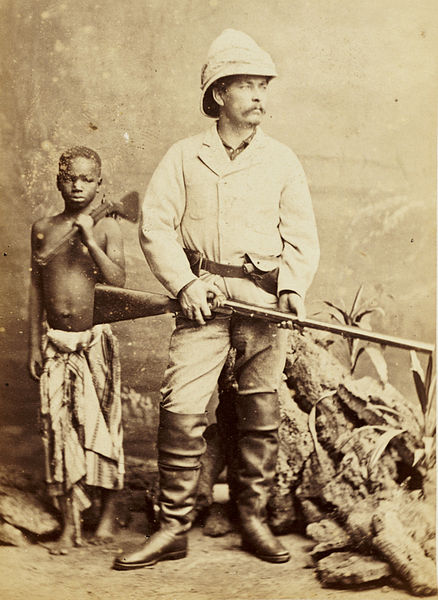

- Explorer Henry Morton Stanley, 1841

PAGE SPONSOR

Leopold II (French: Léopold Louis Philippe Marie Victor, Dutch: Leopold Lodewijk Filips Maria Victor) (9 April 1835 – 17 December 1909) was the king of the Belgians. Born in Brussels the second (but eldest surviving) son of Leopold I and Louise - Marie of Orléans, he succeeded his father to the throne on 17 December 1865 and remained king until his death.

Leopold is chiefly remembered as the founder and sole owner of the Congo Free State, a private project undertaken on his own behalf. He used Henry Morton Stanley to help him lay claim to the Congo, an area now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Powers at the Berlin Conference in

its final Act in 1885, committed the State to improving the lives of

the inhabitants. From the beginning, however, Leopold essentially

ignored these conditions and ran the Congo brutally, using a mercenary

force, for his own personal gain. He extracted a fortune from the Congo,

initially by the collection of ivory, and after a rise in the price of

rubber in the 1890s, by forcing the population to collect sap from

rubber plants. His harsh regime was directly or indirectly responsible

for the death of millions of people. The Congo became one of the most

infamous international scandals of the early 20th century, and Leopold

was ultimately forced to relinquish control of it to the government of

Belgium.

Leopold II married Marie Henriette, Archduchess of Austria, in Brussels on 22 August 1853.

Leopold II also engaged in a religious ceremony with Blanche Zélia Joséphine Delacroix, also known as Caroline Lacroix, a prostitute, on 14 December 1909, with no validity under Belgian law, at the Pavilion of Palms, Royal Palace of Laken, in Brussels, five days before his death. The priest of Laeken Cooreman performed the ceremony.

He was the 973rd Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece in Austria, the 748th Knight of the Order of the Garter in 1866 and the 69th and 321st Grand Cross of the Order of the Tower and Sword.

On 15 November 1902, Italian anarchist Gennaro Rubino attempted to assassinate Leopold, who was riding in a royal cortege from a ceremony in memory of his recently deceased wife, Marie Henriette. After Leopold's carriage passed, Rubino fired three shots at the King; the shots missed Leopold and Rubino was immediately arrested.

In Belgian domestic politics, Leopold emphasized military defense as the basis of neutrality, but he was unable to obtain a universal conscription law until on his death bed. He died in Laeken on 17 December 1909, and was interred in the royal vault at the Church of Our Lady of Laeken in Brussels.

He was succeeded as King of the Belgians by his nephew Albert, son of his brother Philippe.

He was the brother of Empress Carlota of Mexico and first cousin of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom.

Leopold fervently believed that overseas colonies were the key to a country's greatness, and he worked tirelessly to acquire colonial territory for Belgium. Neither the Belgian people nor the Belgian government was interested, however, and Leopold eventually began trying to acquire a colony in his private capacity as an ordinary citizen. The Belgian government lent him money for this venture.

After a number of unsuccessful schemes for colonies in Africa or Asia, in 1876 he organized a private holding company disguised as an international scientific and philanthropic association, which he called the International African Society.

In 1878, under the auspices of the holding company, he hired the famous explorer Henry Morton Stanley to establish a colony in the Congo region. Much diplomatic maneuvering resulted in the Berlin Conference of 1884 – 85, at which representatives of fourteen European countries and the United States recognized Leopold as sovereign of most of the area he and Stanley had laid claim to. On 5 February 1885, the result was the Congo Free State (later becoming, successively, the Belgian Congo, the Republic of the Congo, Zaire, and now the Democratic Republic of the Congo or DRC (not to be confused with Republic of the Congo, formerly owned by France), an area 76 times larger than Belgium, which Leopold was free to rule as a personal domain through his private army, the Force Publique.

The first economic focus of the colony was ivory, but this did not yield the expected levels of revenue. When the global demand for rubber exploded, attention shifted to the labor intensive collection of sap from rubber plants. Abandoning the promises of the Berlin Conference in the late 1890s, the Free State government restricted foreign access and extorted forced labor from the natives. The abuses suffered were horrific, especially in the rubber industry, and included the effective enslavement of the native population, savage beatings, widespread killing, and frequent mutilation when the unrealistic quotas were not met. Missionary John Harris of Baringa, for example, was so shocked by what he had come across that he wrote to Leopold's chief agent in the Congo saying: "I have just returned from a journey inland to the village of Insongo Mboyo. The abject misery and utter abandon is positively indescribable. I was so moved, Your Excellency, by the people's stories that I took the liberty of promising them that in future you will only kill them for crimes they commit."

Estimates of the death toll range from two million to fifteen million. Determining precisely how many people died is next to impossible as accurate records were not kept. Louis and Stengers state that population figures at the start of Leopold's control are only "wild guesses", while E.D. Morel's attempt and others at coming to a figure for population losses were "but figments of the imagination".

Adam Hochschild devotes a chapter of his book, King Leopold's Ghost, to the problem of estimating the death toll. He cites several recent lines of investigation, by anthropologist Jan Vansina and others, examining local sources from police records, religious records, oral traditions, genealogies, personal diaries, and "many others", which generally agree with the assessment of the 1919 Belgian government commission: roughly half the population perished during the Free State period. Since the first official census by the Belgian authorities in 1924 put the population at about 10 million, that implies a rough estimate of 10 million dead.

Smallpox and sleeping sickness also devastated the disrupted population. By 1896 the sleeping sickness had killed up to 5,000 Africans in the village of Lukolela on the Congo River. The mortality figures were collected through the efforts of Roger Casement, who found, for example, only 600 survivors of the disease in Lukolela in 1903.

Reports of outrageous exploitation and widespread human rights abuses led to international outcry in the early 1900s leading to a widespread war of words. The campaign to examine Leopold's regime, led by British diplomat Roger Casement and former shipping clerk E.D. Morel under the auspices of the Congo Reform Association, became the first mass human rights movement. Supporters included American writer Mark Twain, who wrote a stinging political satire entitled King Leopold's Soliloquy, in which the King supposedly argues that bringing Christianity to the country outweighs a little starvation. Rubber gatherers were tortured, maimed and slaughtered until the turn of the century, when the Western world forced Brussels to call a halt. Arthur Conan Doyle also blasted the 'rubber regime' in his 1908 work The Crime of the Congo, written to aid the work of the Congo Reform Association. Doyle contrasted Leopold's rule to the British rule of Nigeria, arguing decency required that those who ruled primitive peoples to be concerned first with their uplift, not how much could be extracted from them. It should be noted that, as Hochschild describes in King Leopold's Ghost, many of Leopold's policies were adopted from Dutch practices in the East Indies, and similar methods were employed to some degree by Germany, France and Portugal where natural rubber occurred in their colonies.

Finally, in 1908, the Belgian parliament compelled the King to cede the Congo Free State to Belgium.

Leopold II is still a controversial figure in the Democratic Republic of Congo. His statue in the capital, Kinshasa,

was removed after independence. Congolese culture minister Christoph

Muzungu decided to reinstate the statue in 2005, pointing out the sense

of liberating progress that had marked the beginning of the Free State

and arguing that people should see the positive aspects of the king as

well as the negative; but just hours after the six meter (20 ft)

statue was erected in the middle of a roundabout near Kinshasa's central

station, it was taken down again without explanation. The Congo

continues, however, to use a variation of the Free State flag, which it

adopted after dropping the name and flag of Zaire.

Though unpopular at the end of his reign — his funeral cortege was booed — Leopold II is remembered today by many Belgians as the "Builder King" (Koning - Bouwer in Dutch, le Roi - Bâtisseur in French) because he commissioned a great number of buildings and urban projects, mainly in Brussels, Ostend and Antwerp. These buildings include the Royal Glasshouses in the grounds of the Palace at Laken, the Japanese Tower, the Chinese Pavilion, the Musée du Congo (now called the Royal Museum for Central Africa), and their surrounding park in Tervuren, the Cinquantenaire in Brussels, and the 1895 - 1905 Antwerpen - Centraal railway station. He also built an important country estate in Saint - Jean - Cap - Ferrat on the French Riviera, including the Villa des Cèdres, which is now a botanical garden. These were all built using the profits from the Congo. In 1900, he created the Royal Trust, by which means he donated most of his property to the Belgian nation.

After the King transferred his private colony to Belgium, there was, as Adam Hochschild puts it in King Leopold's Ghost,

a "Great Forgetting". Hochschild records that, on his visit to the

colonial Royal Museum for Central Africa in the 1990s, there was no

mention of the atrocities committed in the Congo Free State, despite the

museum's large collection of colonial objects. Another example of this

"Great Forgetting" may be found on the boardwalk of Blankenberge,

a popular coastal resort, where a monument shows a colonialist bringing

"civilization" to the black child at his feet. In 2004, an activist

group cut off the hand of a Congolese bronze figure, one of a

multi - figure group in a 1931 sculptural monument to Leopold II on the

beach in Ostend, in protest against the Congo atrocities.

Sir Henry Morton Stanley, GCB, born John Rowlands (28 January 1841 – 10 May 1904), was a Welsh journalist and explorer famous for his exploration of Africa and his search for David Livingstone. Upon finding Livingstone, Stanley allegedly uttered the now famous greeting, "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?"

When Stanley was born in Denbigh, Wales, his mother, Elizabeth Parry, was 19 years old. He never knew his father, who died within a few weeks of his birth; there is some doubt as to his true parentage. His parents were unmarried, so his birth certificate refers to him as a bastard and the stigma of illegitimacy weighed heavily upon him all his life.

Originally

taking his father's name of Rowlands, Stanley was brought up by his

grandfather until the age of five. When his guardian died, Stanley

stayed at first with cousins and nieces for a short time, but was

eventually sent to St. Asaph Union Workhouse for

the poor, where overcrowding and lack of supervision resulted in

frequent abuse by the older boys. When he was ten, his mother and two

siblings stayed for a short while in this workhouse, without Stanley

realizing who they were. He stayed until the age of 15. After completing

an elementary education, he was employed as a pupil teacher in a National School.

In 1859, at the age of 18, he made his passage to the United States in search of a new life. Upon arriving in New Orleans, he absconded from his boat. According to his own declarations, he became friendly with a wealthy trader named Henry Hope Stanley, by accident: he saw Stanley sitting on a chair outside his store and asked him if he had any job opening for a person such as himself. However, he did so in the British style, "Do you want a boy, sir?" As it happened, the childless man had indeed been wishing he had a boy of his own, and the inquiry led not only to a job, but to a close relationship. The youth ended up taking Stanley's name. Later, he would write that his adoptive parent had died only two years after their meeting, but in fact the elder Stanley did not die until much later, in 1878. In any case, young Stanley assumed a local accent and began to deny being a foreigner.

Stanley participated reluctantly in the American Civil War, first joining the Confederate Army and fighting in the Battle of Shiloh in 1862. After being taken prisoner he was recruited at Camp Douglas, Illinois, by its commander, Col. James A. Mulligan, as a "Galvanized Yankee" and joined the Union Army on 4 June 1862, but was discharged 18 days later due to severe illness. Recovering, he served on several merchant ships before joining the Navy in July 1864. On board the Minnesota he became a record keeper, which led to freelance journalism. Stanley and a junior colleague jumped ship on 10 February 1865 in New Hampshire, in search of greater adventures. Stanley thus became possibly the only man to serve in the Confederate Army, the Union Army, and the Union Navy.

Following the Civil War, Stanley began a career as a journalist. As part of this new career, Stanley organized an expedition to the Ottoman Empire that ended catastrophically when Stanley was imprisoned. He eventually talked his way out of jail and even received restitution for damaged expedition equipment. This early expedition may have formed the foundation for his eventual exploration of the Congo region of Africa.

In

1867, Stanley was recruited by Colonel Samuel Forster Tappan (a

one time journalist) of the Indian Peace Commission, to serve as a

correspondent to cover the work of the Commission for several

newspapers. Stanley was soon retained exclusively by James Gordon Bennett (1795 – 1872), founder of the New York Herald,

who was impressed by Stanley's exploits and by his direct style of

writing. He describes this early period of his professional life in

Volume I of his book My Early Travels and Adventures in America and Asia (1895). He became one of the Herald's overseas correspondents and, in 1869, was instructed by Bennett's son to find the Scottish missionary and explorer David Livingstone, who was known to be in Africa but had not been heard from for some time. According to Stanley's account, he asked James Gordon Bennett, Jr. (1841 – 1918), who had succeeded to the paper's management after his father's

retirement in 1867, how much he could spend. The reply was "Draw

£1,000 now, and when you have gone through that, draw another

£1,000, and when that is spent, draw another £1,000, and

when you have finished that, draw another £1,000, and so on — BUT

FIND LIVINGSTONE!",

In actuality, Stanley had lobbied his employer for several years to

mount this expedition which presumably would lead to fame and fortune.

Stanley traveled to Zanzibar in March 1871 and outfitted an expedition with the best of everything, requiring no fewer than 200 porters. This 7,000 miles (11,000 km) expedition through the tropical forest became a nightmare. His thoroughbred stallion died within a few days after a bite from a Tsetse fly, many of his carriers deserted and the rest were decimated by tropical diseases.

Some recent authors suggest that Stanley's treatment of indigenous porters helps to refute his reputation for brutality. However, statements by contemporaries of Stanley like Sir Richard Francis Burton, who claimed "Stanley shoots negroes as if they were monkeys", paint a very different picture. Stanley found Livingstone on 10 November 1871, in Ujiji near Lake Tanganyika in present day Tanzania, and may have greeted him with the now famous, "Doctor Livingstone, I presume?" This famous phrase may be a fabrication, as Stanley tore out of his diary the pages relating to the encounter. Even Livingstone's account of the encounter fails to mention these words. However, a summary of Stanley's letters published by The New York Times on 2 July 1872, quotes the phrase. However, Tim Jeal argues in his biography that Stanley invented it afterwards because of his "insecurity about his background".

The Herald's own first account of the meeting, published 2 July 1872, also includes the phrase: "Preserving a calmness of exterior before the Arabs which was hard to simulate as he reached the group, Mr. Stanley said: – `Doctor Livingstone, I presume?' A smile lit up the features of the hale white man as he answered: "Yes, and I feel thankful that I am here to welcome you."

Stanley

joined Livingstone in exploring the region, establishing for certain

that there was no connection between Lake Tanganyika and the River Nile. On his return, he wrote a book about his experiences : How I Found Livingstone; travels, adventures, and discoveries in Central Africa. This brought him into the public eye and gave him some financial success.

In 1874, the New York Herald, in partnership with Britain's Daily Telegraph, financed Stanley on another expedition to the African continent. One of his missions was to solve a last great mystery of African exploration by tracing the course of the Congo River to the sea. The difficulty of this expedition is hard to overstate. Stanley used sectional boats to pass the great cataracts separating the Congo into distinct tracts. After 999 days, on 9 August 1877, Stanley reached a Portuguese outpost at the mouth of the Congo River. Starting with 356 people, only 114 had survived the expedition, of whom Stanley was the only European.

He wrote about his trials in his book Through the Dark Continent.

Stanley was approached by the ambitious Belgian king Leopold II, who in 1876 had organized a private holding company disguised as an international scientific and philanthropic association, which he called the International African Society. The king spoke of his intentions to introduce Western civilization and bring religion to that part of Africa, but did not mention he wanted to claim the lands. Stanley returned to the Congo, negotiated with local leaders, and obtained concessions.

At

the end of his life, he was embittered by the growing perception that

his establishment of a Congo Free State was mitigated by its

unscrupulous government; in his defense for having imposed Christian

civilization, it was maintained that Stanley had "only been responsible

for the death of six or seven hundred negroes.... and all these negroes

fell as the result of attacking Stanley." In addition, the spread of African trypanosomiasis across central Africa is attributed to the movements of Stanley's enormous baggage train and the Emin Pasha relief expedition.

In 1886, Stanley led the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition to "rescue" Emin Pasha, the governor of Equatoria in the southern Sudan. King Leopold II demanded that Stanley take the longer route, via the Congo river, hoping to acquire more territory and perhaps even Equatoria. After immense hardships and great loss of life, Stanley met Emin in 1888, charted the Ruwenzori Range and Lake Edward, and emerged from the interior with Emin and his surviving followers at the end of 1890. But this expedition tarnished Stanley's name because of the conduct of the other Europeans: British gentlemen and army officers. An army major was shot by a carrier, after behaving with extreme cruelty. James Jameson, heir to an Irish whiskey manufacturer, bought an eleven year old girl and offered her to cannibals in order to document and sketch how she was cooked and eaten. Stanley only found out when Jameson had died of fever.

On his return to Europe, he married Welsh artist Dorothy Tennant, and they adopted a child, Denzil, who in 1954, donated some 300 items to the Stanley archives at the Royal Museum of Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium. Denzil died in 1959. Stanley entered Parliament as Liberal Unionist member for Lambeth North, serving from 1895 to 1900. He became Sir Henry Morton Stanley when he was made a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath in 1899, in recognition of his service to the British Empire in Africa.

He died in London on 10 May 1904; at his funeral, he was eulogized by Daniel P. Virmar. His grave, in the churchyard of St. Michael's Church in Pirbright, Surrey, is marked by a large piece of granite inscribed with the words "Henry Morton Stanley, Bula Matari, 1841 – 1904, Africa". Bula Matari, which translates as "Breaker of Rocks" or "Breakstones" in Kikongo, was Stanley's name among locals in Congo. It can be translated as a term of endearment: for as the leader of Leopold's expedition, he commonly worked with the laborers breaking rocks with which they built the first modern road along the Congo River. It can also be translated in far less flattering terms, and it was suggested by Adam Hochschild that while Stanley understood it as an heroic epithet, his Congolese companions understood it in a mocking and pejorative tone.

Stanley wrote in Through the Dark Continent that "the savage only respects force, power, boldness, and decision." His legacy of death and destruction in the Congo region is considered an inspiration for Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness.

In 1939, a popular film called Stanley and Livingstone was released, with Spencer Tracy as Stanley and Cedric Hardwicke as Livingstone.

Stanley appears as a character in Simon Gray's 1978 play The Rear Column, which tells the story of the men left behind to wait for Tippu Tib while Stanley went on to relieve Emin Pasha.

An NES game based on his life was released in 1992 called "Stanley: The Search for Dr. Livingston".

In 1997, a made - for - television film, Forbidden Territory: Stanley's Search for Livingstone, was produced by National Geographic. Stanley was portrayed by Aidan Quinn and Livingstone was portrayed by Nigel Hawthorne.

Stanley Electric Co., Ltd. of Japan, uses Stanley's family name in honor of his discoveries "that have brought light into many spots of the world undiscovered and hitherto unknown to mankind". The company produces light emitting diodes, liquid crystal displays and lamps.

His great grandson, Richard Stanley, is a South African filmmaker and directs documentaries.

There is a hospital in St. Asaph, North Wales, named after Stanley in honor of his birth in the area. It was the former workhouse in which he spent much of his early life. memorials to H M Stanley have recently been erected in St Asaph (which has caused local controversy for being phalic shaped) and in Denbigh (a statue of H M Stanley with an outstretched hand).

In 1971 the BBC produced a six part dramatized documentary series, Search for the Nile. Much of the series was shot on location, with Stanley played by Keith Buckley.

The 2009 History Channel series, Expedition Africa, documents a group of explorers attempting to traverse the route of Stanley's expedition in search of Livingstone.