<Back to Index>

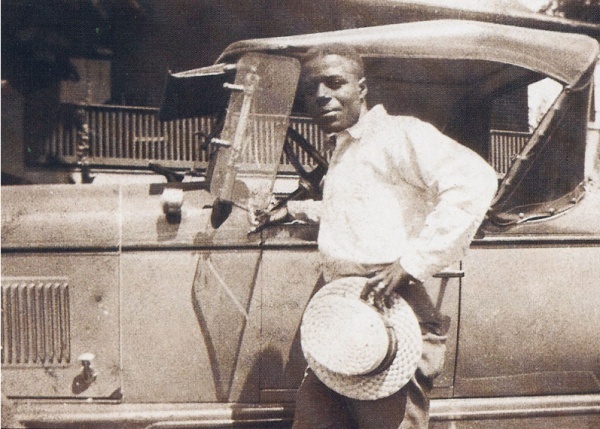

- Bluesman Nehemiah Curtis "Skip" James, 1902

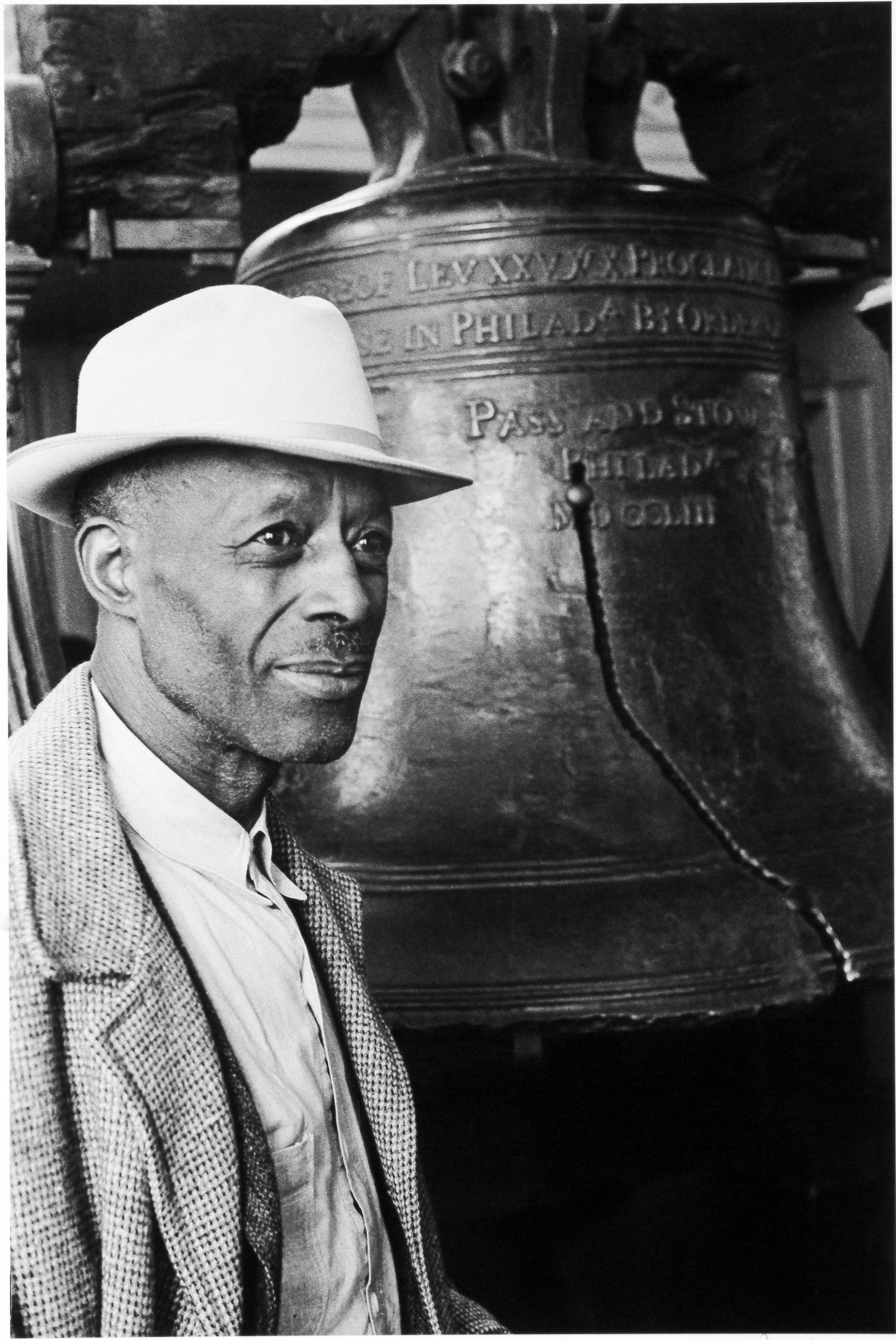

- Bluesman Eddie James "Son" House, Jr., 1902

- Bluesman Joseph Lee "Big Joe" Williams, 1903

PAGE SPONSOR

Nehemiah Curtis "Skip" James (June 9, 1902 – October 3, 1969) was an American Delta blues singer, guitarist, pianist and songwriter, born in Bentonia, Mississippi, died in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

He first learned to play guitar from another bluesman from the area, Henry Stuckey. His guitar playing is noted for its dark, minor sound, played in an open D-minor tuning with an intricate fingerpicking technique. James first recorded for Paramount Records in 1931, but these recordings sold poorly due to the Great Depression, and he drifted into obscurity. After a long absence from the public eye, James was "rediscovered" in 1964 by three blues enthusiasts, helping further the blues and folk music revival of the 1950s and early 60s. During this period, James appeared at several folk and blues festivals and gave live concerts around the country, also recording several albums for various record labels.

His songs have influenced several generations of musicians, being adapted or covered by Kansas Joe McCoy, Robert Johnson, Cream, Deep Purple, Chris Thomas King, Alvin Youngblood Hart, The Derek Trucks Band, Beck, Big Sugar, and Rory Block. He is hailed as "one of the seminal figures of the blues."

James was born near Bentonia, Mississippi. His father was a converted bootlegger turned preacher. As a youth, James heard local musicians such as Henry Stuckey and brothers Charlie and Jesse Sims and began playing the organ in his teens. He worked on road construction and levee building crews in his native Mississippi in the early 1920s, and wrote what is perhaps his earliest song, "Illinois Blues," about his experiences as a laborer.

Later in the '20s he sharecropped and made bootleg whiskey in the Bentonia area. He began playing guitar in open D-minor tuning and developed the three - finger picking technique heard in his

recordings. In addition, he began to practice piano playing, drawing

inspiration from the Mississippi blues pianist Little Brother Montgomery.

In early 1931, James auditioned for Jackson, Mississippi, record shop owner and talent scout H.C. Speir, who placed blues performers with a variety of record labels including Paramount Records. On the strength of this audition, James traveled to Grafton, Wisconsin, to record for Paramount. James's 1931 work is considered idiosyncratic among pre-war blues recordings, and formed the basis of his reputation as a musician.

As is typical of his era, James recorded a variety of material — blues and spirituals, cover versions and original compositions — frequently blurring the lines between genres and sources. For example, "I'm So Glad" was derived from a 1927 song by Art Sizemore and George A. Little entitled "So Tired", which had been recorded in 1928 by both Gene Austin and Lonnie Johnson (the latter under the title "I'm So Tired of Livin' All Alone"). Biographer Stephen Calt, echoing the opinion of several critics, considered the finished product totally original, "one of the most extraordinary examples of fingerpicking found in guitar music".

Several of the Grafton recordings, such as "Hard Time Killing Floor Blues", "Devil Got My Woman", "Jesus Is A Mighty Good Leader", and "22 - 20 Blues" (the basis for Robert Johnson's better known "32 - 20 Blues", and the band name for the English group 22 - 20s), have proven similarly influential. Very few original copies of James's Paramount 78 RPMs have survived.

The Great Depression struck just as James' recordings were hitting

the market. Sales were poor as a result, and James gave up performing

the blues to become the choir director in his father's church. James himself was later ordained as a minister in both the Baptist and Methodist denominations, but the extent of his involvement in religious activities is unknown.

For the next thirty years, James recorded nothing and drifted in and out of music. He was virtually unknown to listeners until about 1960. In 1964 blues enthusiasts John Fahey, Bill Barth and Henry Vestine found him in a hospital in Tunica, Mississippi. According to Calt, the "rediscovery" of both James and of Son House at virtually the same moment was the start of the "blues revival" in the US. In July 1964 James, along with other rediscovered performers, appeared at the Newport Folk Festival. Several photographs by Dick Waterman captured this first performance in over 30 years. Throughout the remainder of the decade, he recorded for the Takoma, Melodeon, and Vanguard labels and played various engagements until his death in Philadelphia from cancer in 1969.

Although James was not initially covered as frequently as other rediscovered musicians, British rock band Cream recorded "I'm So Glad" (a studio version and a live version), providing James with the only windfall of his career. Deep Purple also covered "I'm So Glad," on Shades of Deep Purple, and English blues rock band 22 - 20s named themselves after "22 - 20 Blues." Singer Dion DiMucci released an album in November 2007 titled Son of Skip James.

Since his death, James's music has become more available and prevalent than during his lifetime — his 1931 recordings, along with several rediscovery recordings and concerts, have found their way on to numerous compact discs, drifting in and out of print. His influence is still felt among contemporary bluesmen. James also left a mark on Hollywood, as well, with Chris Thomas King's cover of "Hard Time Killing Floor Blues" on O Brother, Where Art Thou?, and the 1931 "Devil Got My Woman" featured in the plot and soundtrack of Ghost World. In recent times, British post - rock band Hope of the States released a song partially focused on the life of Skip James entitled "Nehemiah", which charted at number 30 in the UK Singles Chart. "He's a Mighty Good Leader" was also covered by Beck on his 1994 album One Foot in the Grave.

James was known to be an aloof and moody person. "Skip James, you never knew. Skip could be sunshine, or thunder and lightning depending on his whim of the moment" commented Dick Spottswood on James's personality. He seldom socialized with other bluesmen and fans. Like John Fahey, James loathed the so-called "folkie" scene of the 1960s. He held a high regard for his own work and was reluctant to share musical ideas with other performers. Though the lyrical content of some of his songs led to the characterization of James as a misogynist, he remained with his wife Lorenzo (niece of Mississippi John Hurt) until his death. He is buried with his wife at a private cemetery (Merion Memorial Park) just outside of Philadelphia in Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania.

James often played his guitar with an open D-minor tuning (DADFAD), resulting in the "deep" sound of the 1931 recordings. James purportedly learned this tuning from his musical mentor, the unrecorded bluesman Henry Stuckey. Stuckey in turn was said to have acquired it from Bahamanian soldiers during the First World War, despite the fact that his service card shows he didn't serve overseas. Robert Johnson also recorded in this tuning, his "Hell Hound On My Trail" being based on James' "Devil Got My Woman." James' classically informed, finger picking style was fast and clean, using the entire register of the guitar with heavy, hypnotic bass lines. James' style of playing had more in common with the Piedmont blues of the East Coast than with the Delta blues of his native Mississippi.

James is sometimes associated with the Bentonia School, which is either a sub - genre of blues music or a style of playing it. Calt, in his 1994 biography of James, I'd Rather Be the Devil: Skip James and the Blues, maintains that there was indeed no style of blues that originated in Bentonia, and that this is simply a notion of later blues writers who overestimated the provinciality of Mississippi during the early 20th century, when railways linked small towns, and who failed to see that in the case of Jack Owens, "the 'tradition' he bore primarily consisted of musical scraps from James' table". Owens and other musicians who may have been contemporaries of James were not recorded until the 60s revival period. As such, the extent to which the work of said musicians is indicative of any "school", and whether James originated it or was simply a "member", remains an open question.

James, despite poor health, recorded several LPs worth of music, mostly

revisiting his 1931 sides, traditional music, and spirituals; but along

with these, he sang a handful of newly penned blues meditating on his

illness and convalescence. Unfortunately, these five prolific years have

not been thoroughly documented: recordings, outtakes, and interviews

not released on James's few proper LPs (which, themselves, have been

endlessly cannibalized and reissued) are scattered among many small

label compilations. Previously unreleased performances continue to be

found, released, and left largely unexplained — sometimes hours' worth

at a time.

Eddie James "Son" House, Jr. (March 21, 1902 (?) – October 19, 1988) was an American blues singer and guitarist. House pioneered an innovative style featuring strong, repetitive rhythms, often played with the aid of slide guitar, and his singing often incorporated elements of southern gospel and spiritual music. House did not learn guitar until he was in his early twenties, as he had been "churchified", and was determined to become a Baptist preacher. He associated himself with Delta blues musicians Charlie Patton and Willie Brown, often acting as a sideman. In 1930, House made his first recordings for Paramount Records during a session for Charlie Patton. However, these did not sell well due to the Great Depression, and he drifted into obscurity. He was recorded by John and Alan Lomax for the Library of Congress in 1941 and '42. Afterwards, he moved north to Rochester, New York, where he remained until his rediscovery in 1964, spurred by the American folk blues revival. Over the next few years, House recorded several studio albums and went on various tours until his death in 1988. His influence has extended over a wide area of musicians, including Robert Johnson, John Hammond, Alan Wilson (of Canned Heat), Bonnie Raitt, The White Stripes, and John Mooney.

The middle of three brothers, House was born in Riverton, two miles from Clarksdale, Mississippi. Around age seven or eight, he was brought by his mother to Tallulah, Louisiana, after his parents separated. The young Son House was determined to become a Baptist preacher, and at age 15 began his preaching career. Despite the church's firm stand against blues music and the sinful world which revolved around it, House became attracted to it and taught himself guitar in his mid 20s, after moving back to the Clarksdale area, inspired by the work of Willie Wilson.

After killing a man, allegedly in self defense, he spent time at the Mississippi State Penitentiary (Parchman Farm) in 1928 and 1929. The official story on the killing is that sometime around 1927 or 1928, he was playing in a juke joint

when a man went on a shooting spree. Son was wounded in the leg, and

shot the man dead. He received a 15 year sentence at Parchman Farm

prison, of which he served two years. He then moved to Lula, Mississippi, where he first met Charlie Patton and Willie Brown (around this same time, he also met Robert Johnson). The three began playing alongside each other during local gigs.

In 1930, Art Laibly of Paramount Records traveled to Lula to convince Patton to record several more sides in Grafton, Wisconsin. Along with Patton came House, Brown, and pianist Louise Johnson, who would all end up recording sides for the label. House recorded nine songs during that session, eight of which were released; but these were commercial failures, and House would not record again commercially in 35 years. House continued to play with Patton and Brown, even after Patton's death in 1934. During this time, House worked as a tractor driver for various plantations around the Lake Comororant area.

Alan Lomax first recorded House for the Library of Congress in 1941. Willie Brown, mandolin player Fiddlin' Joe Martin, and harmonica player Leroy Williams

played with House on these recordings. Lomax returned to the area in

1942, where he recorded House once more. He then faded from the public

view, moving to Rochester, New York, in 1943, working as a railroad porter for the New York Central Railroad and as a chef.

In 1964, after a long search of the Mississippi Delta region by Nick Perls, Dick Waterman and Phil Spiro, he ended up being "rediscovered" in Rochester, NY. House had been retired from the music business for many years, and was unaware of the 1960s folk blues revival and international enthusiasm regarding his early recordings.

He subsequently toured extensively in the US and Europe and recorded for CBS Records. Like Mississippi John Hurt, he was welcomed into the music scene of the 1960s and played at the Newport Folk Festival in 1964, the New York Folk Festival in July 1965, and the October 1967 European tour of the American Folk Festival along with Skip James and Bukka White.

The young guitarist Alan Wilson (Canned Heat) was one of Son House's biggest fans. The producer John Hammond Sr. asked Alan Wilson, who was just 22 years old, to teach "Son House how to play like Son House," because Alan Wilson had such a good knowledge of the blues styles. The album The Father of Delta Blues - The Complete 1965 Sessions was the result. Son House played with Alan Wilson live. It can be heard on the album John the Revelator: The 1970 London Sessions.

In the summer of 1970, House toured Europe once again, including an appearance at the Montreux Jazz Festival; a recording of his London concerts was released by Liberty Records. He also played at the two Days of Blues Festival in Toronto in 1974.

Ill health plagued his later years and in 1974 he retired once again, and later moved to Detroit, Michigan, where he remained until his death from cancer of the larynx. He was buried at the Mt. Hazel Cemetery. Members of the Detroit Blues Society raised money through benefit concerts to put a monument on his grave. He had been married five times.

House's innovative style featured strong, repetitive rhythms, often played with the aid of a bottleneck, coupled with singing that owed more than a nod to the field hollers of the chain gangs. Describing House's 1967 appearance at the De Montfort Hall in Leicester, England, Bob Groom wrote in Blues World magazine:

It is difficult to describe the transformation that took place as this smiling, friendly man hunched over his guitar and launched himself, bodily it seemed, into his music. The blues possessed him like a 'lowdown shaking chill' and the spellbound audience saw the very incarnation of the blues as, head thrown back, he hollered and groaned the disturbing lyrics and flailed the guitar, snapping the strings back against the fingerboard to accentuate the agonized rhythm. Son's music is the centre of the blues experience and when he performs it is a corporeal thing, audience and singer become as one.

House was the primary influence on Muddy Waters and also an important influence on Robert Johnson. It was House who, speaking to awestruck young blues fans in the 1960s, spread the legend that Johnson had sold his soul to the Devil in exchange for his musical powers.

More recently, House's music has influenced the blues - rock group The White Stripes, who covered his song "Death Letter" (also reworked by Skip James and Robert Johnson) on their album De Stijl, and later performed it at the 2004 Grammy Awards. The version on De Stijl contains five of the verses from the Son House original. The eighth verse (one of the ones that was left off) was added to the song "Dead Leaves And The Dirty Ground" on their third album White Blood Cells.

The White Stripes incorporated sections of a traditional song Son House recorded — "John the Revelator" — into the song "Cannon" from their eponymous debut album The White Stripes. Jack White of The White Stripes has cited House's a cappella song, "Grinnin' in Your Face", as his favorite song.

Another musician deeply influenced by Son House is the slide player John Mooney, who in his teens learned slide guitar from Son House while House was living in Rochester, New York.

Several of House's songs were featured in the motion picture soundtrack of Black Snake Moan (2006).

Joseph Lee Williams (October 16, 1903 – December 17, 1982), billed throughout his career as Big Joe Williams, was an American Delta blues guitarist, singer and songwriter, notable for the distinctive sound of his nine - string guitar. Performing over four decades, he recorded such songs as "Baby Please Don't Go", "Crawlin' King Snake" and "Peach Orchard Mama" for a variety of record labels, including Bluebird, Delmark, Okeh, Prestige and Vocalion. Williams was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame on October 4, 1992.

Blues historian Barry Lee Pearson (Sounds Good to Me: The Bluesman's Story, Virginia Piedmont Blues) attempted to document the gritty intensity of the Williams persona in this description:

- "When I saw him playing at Mike Bloomfield's "blues night" at the Fickle Pickle, Williams was playing an electric nine - string guitar through a small ramshackle amp with a pie plate nailed to it and a beer can dangling against that. When he played, everything rattled but Big Joe himself. The total effect of this incredible apparatus produced the most buzzing, sizzling, African - sounding music I have ever heard".

Born in Crawford, Mississippi, Williams as a youth began wandering across the United States busking and playing stores, bars, alleys and work camps. In the early 1920s he worked in the Rabbit Foot Minstrels revue and recorded with the Birmingham Jug Band in 1930 for the Okeh label.

In 1934, he was in St. Louis, where he met record producer Lester Melrose who signed him to Bluebird Records in 1935. He stayed with Bluebird for ten years, recording such blues hits as "Baby, Please Don't Go" (1935) and "Crawlin' King Snake" (1941), both songs later covered by many other performers. He also recorded with other blues singers, including Sonny Boy Williamson I, Robert Nighthawk and Peetie Wheatstraw.

Williams remained a noted blues artist in the 1950s and 1960s, with his guitar style and vocals becoming popular with folk - blues fans. He recorded for the Trumpet, Delmark, Prestige and Vocalion labels, among others. He became a regular on the concert and coffeehouse circuits, touring Europe and Japan in the late 1960s and early 1970s and performing at major U.S. music festivals.

Marc Miller described a 1965 performance in Greenwich Village:

- "Sandwiched in between the two sets, perhaps as an afterthought, was the bluesman Big Joe Williams (not to be confused with the jazz and rhythm and blues singer Joe Williams who sang with Count Basie). He looked terrible. He had a big bulbous aneuristic protrusion bulging out of his forehead. He was equipped with a beat up old acoustic guitar which I think had nine strings and sundry homemade attachments and a wire hanger contraption around his neck fashioned to hold a kazoo while keeping his hands free to play the guitar. Needless to say, he was a big letdown after the folk rockers. My date and I exchanged pained looks in empathy for what was being done this Delta blues man who was ruefully out of place. After three or four songs the unseen announcer came on the p. a. system and said, "Lets have a big hand for Big Joe Williams, ladies and gentlemen; thank you, Big Joe". But Big Joe wasn't finished. He hadn't given up on the audience, and he ignored the announcer. He continued his set and after each song the announcer came over the p. a. and tried to politely but firmly get Big Joe off the stage. Big Joe was having none of it, and he continued his set with his nine - string acoustic and his kazoo. Long about the sixth or seventh song he got into his groove and started to wail with raggedy slide guitar riffs, powerful voice, as well as intense percussion on the guitar and its various accoutrements. By the end of the set he had that audience of jaded '60s rockers on their feet cheering and applauding vociferously. Our initial pity for him was replaced by wondrous respect. He knew he had it in him to move that audience, and he knew that thousands of watts and hundreds of decibels do not change one iota the basic power of a song".

Williams' guitar playing was in the Delta blues

style, and yet was unique. He played driving rhythm and virtuosic lead

lines simultaneously and sang over it all. He played with picks both on

his thumb and index finger, plus his guitar was heavily modified. Williams added a rudimentary electric pick - up,

whose wires coiled all over the top of his guitar. He also added three

extra strings, creating unison pairs for the first, second and fourth

strings. His guitar was usually tuned to Open G, like such: (D2 G2 D3D3

G3 B3B3 D4D4), with a capo placed on the second fret to set the tuning

to the key of A. During the 1920s and 1930s, Williams had gradually

added these extra strings in order to keep other guitar players from

being able to play his guitar. In his later years, he would also

occasionally use a 12 string guitar with all strings tuned in unison to

Open G. Williams sometimes tuned a six - string guitar to an interesting

modification of Open G. In this modified tuning, the bass D string (D2)

was replaced with a .08 gauge string and tuned to G4. The resulting

tuning was (G4 G2 D3 G3 B3 D4), with the G4 string being used as a

melody string. This tuning was used exclusively for slide playing.

He died December 17, 1982 in Macon, Mississippi. Williams was buried in a private cemetery outside Crawford near the Lowndes County line. His headstone was primarily paid for by friends and partially funded by a collection taken up among musicians at Clifford Antone's nightclub in Austin, Texas, organized by California music writer Dan Forte, and erected through the Mt. Zion Memorial Fund on October 9, 1994. Harmonica virtuoso and one time touring companion of Williams, Charlie Musselwhite, delivered the eulogy at the unveiling. Williams' headstone epitaph, composed by Forte, proclaims him "King of the 9 String Guitar."

Remaining funds raised for Williams' memorial were donated by the Mt. Zion Memorial Fund to the Delta Blues Museum in order to purchase the last nine - string guitar from Williams' sister Mary May. The guitar purchased by the Museum is actually a 12 string guitar that Williams used in his later days. The last nine - string (a 1950s Kay cutaway converted to Williams' nine - string specifications) is missing at this time. Williams' previous nine - string (converted from a 1944 Gibson L-7) is in the possession of Williams' road agent and fellow traveler, Blewett Thomas.

One of Williams' nine - string guitars can be found under the counter of the Jazz Record Mart in Chicago, which is owned by Bob Koester, the founder of Delmark Records. Williams can be seen playing the nine - string guitar in American Folk-Blues Festival: The British Tours, 1963 - 1966, a 2007 DVD release.

"When I went back down South, boy, they'd put me up on top of a house to hear me play."