<Back to Index>

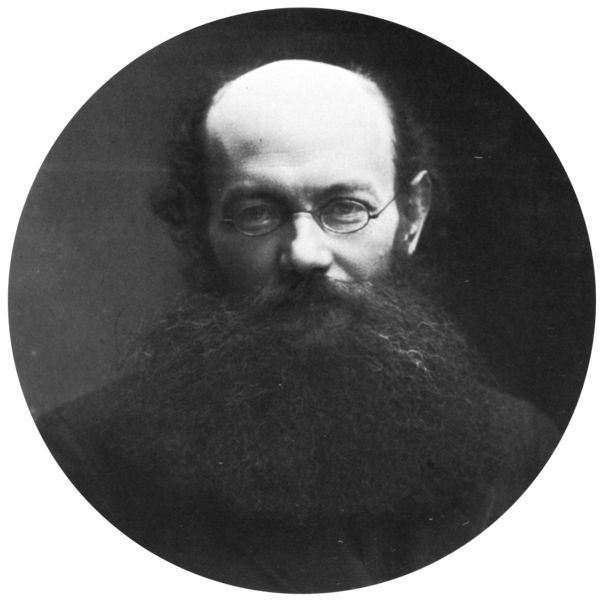

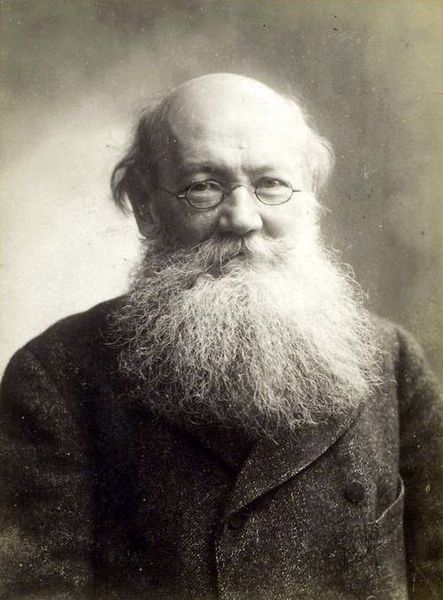

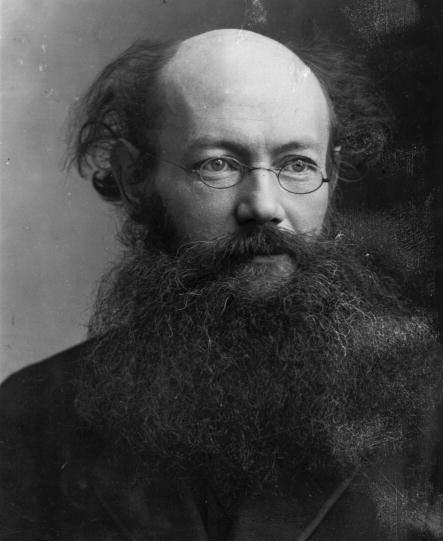

- Scientist and Philosopher Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin, 1842

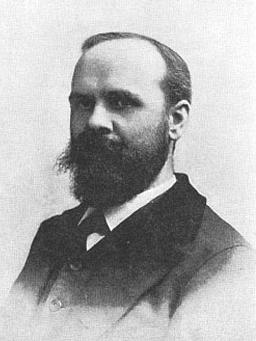

- Editor and Publisher Benjamin Ricketson Tucker, 1854

PAGE SPONSOR

Prince Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (Russian: Пётр Алексе́евич Кропо́ткин; 9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian zoologist, evolutionary theorist, philosopher, scientist, revolutionary, economist, activist, geographer, writer and one of the world's foremost anarcho - communists. Kropotkin advocated a communist society free from central government and based on voluntary associations between workers. He wrote many books, pamphlets and articles, the most prominent being The Conquest of Bread and Fields, Factories and Workshops, and his principal scientific offering, Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution. He also contributed the article on anarchism to the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition.

Peter Kropotkin was born in Moscow. His father, Prince Alexei Petrovich Kropotkin, owned large tracts of land and nearly 1200 "souls" (male serfs) in three provinces. Kropotkin's male line traced to the legendary prince Rurik; his mother was the daughter of a Russian general. "[U]nder the influence of republican teachings," he dropped his princely title at the age of twelve, and "even rebuked his friends, when they so referred to him."

In 1857, at age 14, Kropotkin enrolled in the Corps of Pages at St. Petersburg. Only 150 boys — mostly children of nobility belonging to the court — were educated in this privileged corps, which combined the character of a military school endowed with special rights and of a court institution attached to the imperial household. Kropotkin's memoirs detail the hazing and other abuse of pages for which the Corps had become notorious.

In Moscow, Kropotkin had developed an interest in the condition of the peasantry, and this interest increased as he grew older. In St. Petersburg, he read widely on his own account, and gave special attention to the works of the French encyclopædists and to French history. The years 1857 - 1861 witnessed a growth in the intellectual forces of Russia, and Kropotkin came under the influence of the new liberal - revolutionary literature, which largely expressed his own aspirations.

In 1862, Kropotkin was promoted from the Corps of Pages to the army.

The members of the corps had the prescriptive right to choose the

regiment to which they would be attached. For some time, he was aide de camp to the governor of Transbaikalia at Chita. Later he was appointed attaché for Cossack affairs to the governor - general of East Siberia at Irkutsk.

Administrative work was scarce, and in 1864 Kropotkin accepted charge of a geographical survey expedition, crossing North Manchuria from Transbaikalia to the Amur, and soon was attached to another expedition which proceeded up the Sungari River into the heart of Manchuria. The expeditions yielded valuable geographical results. The impossibility of obtaining any real administrative reforms in Siberia now induced Kropotkin to devote himself almost entirely to scientific exploration, in which he continued to be highly successful.

In 1867, he quit the army and returned to St. Petersburg, where he entered the university, becoming at the same time secretary to the geography section of the Russian Geographical Society. This action caused his father to disinherit him, "leaving him a 'prince' with no visible means of support." In 1871, he explored the glacial deposits of Finland and Sweden for the Society. In 1873, he published an important contribution to science, a map and paper in which he showed that the existing maps entirely misrepresented the physical features of Asia; the main structural lines were in fact from southwest to northeast, not from north to south or from east to west as had been previously supposed. During this work, he was offered the secretaryship of the Society, but he had decided that it was his duty not to work at fresh discoveries but to aid in diffusing existing knowledge among the people at large. Accordingly, he refused the offer and returned to St. Petersburg, where he joined the revolutionary party.

In 1874, Kropotkin delivered his report on the subject of the Ice Age, where he argued that it had taken place in not as distant a past as originally thought. He was arrested by the Tsar's secret police the next day, on March 22, 1874, charged with membership in the banned revolutionary society, and incarcerated in the Peter and Paul Fortress. Despite the incarceration, Kropotkin was allowed to continue his scientific research and produced several new important papers there.

He visited Switzerland in 1872 and became a member of the International Workingmen's Association (IWA) at Geneva. It was there that he found that he did not like IWA's style of socialism. Instead, he studied the program of the more radical Jura federation at Neuchâtel

and spent time in the company of the leading members, and adopted the

creed of anarchism. On returning to Russia, he took an active part in

spreading revolutionary propaganda through the nihilist - led Circle of Tchaikovsky.

In 1873 Kropotkin was arrested and imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress. He gained notoriety for his widely publicized escape from the prison in 1876, after which he went to England, moving after a short stay to Switzerland where he joined the Jura Federation. In 1877 he moved to Paris, where he helped to start the socialist movement. In 1878 he returned to Switzerland where he edited for Jura Federation's revolutionary newspaper Le Révolté, and published various revolutionary pamphlets. He was outspoken in his beliefs that the peasants were being treated unfairly and deserved to have the same land as the lords.

In 1881 shortly after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II, the Swiss government expelled Kropotkin from Switzerland. After a short stay at Thonon (Savoy), he went to London where he stayed nearly a year and returned to Thonon in late 1882. Soon he was arrested by the French government, tried at Lyon, and sentenced by a police court magistrate (under a special law passed on the fall of the Paris Commune) to five years' imprisonment, on the ground that he had belonged to the IWA (1883). The French Chamber repeatedly agitated on his behalf, and he was released in 1886. He settled near London, living at various times in Harrow – where his daughter, Alexandra, was born – Ealing and Bromley (6 Crescent Road 1886 - 1914). He also lived for a number of years in Brighton. While living in London, Kropotkin became friends with a number of prominent English speaking socialists, including William Morris and George Bernard Shaw.

In 1902 Kropotkin published the book Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, which provided an alternative view on animal and human survival, beyond the claims of interpersonal competition and natural hierarchy proffered at the time by some "social Darwinists", such as Francis Galton. He argued "that it was an evolutionary emphasis on cooperation instead of competition in the Darwinian sense that made for the success of species, including the human."

In the animal world we have seen that the vast majority of species live in societies, and that they find in association the best arms for the struggle for life: understood, of course, in its wide Darwinian sense – not as a struggle for the sheer means of existence, but as a struggle against all natural conditions unfavorable to the species. The animal species, in which individual struggle has been reduced to its narrowest limits, and the practice of mutual aid has attained the greatest development, are invariably the most numerous, the most prosperous, and the most open to further progress. The mutual protection which is obtained in this case, the possibility of attaining old age and of accumulating experience, the higher intellectual development, and the further growth of sociable habits, secure the maintenance of the species, its extension, and its further progressive evolution. The unsociable species, on the contrary, are doomed to decay.

— Peter Kropotkin, Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (1902), Conclusion.

Kropotkin's authority as a writer on Russia is generally acknowledged, and he contributed to many articles. Most of the other 90 articles are about various aspects of Russian geography.

Kropotkin returned to Russia after the February Revolution and was offered the ministry of education in the provisional government; he rejected the post. His enthusiasm for the changes happening in the Russian Empire turned to disappointment when the Bolsheviks seized power in the October Revolution. "This buries the revolution," he said. He thought that the Bolsheviks had shown how the revolution was not to be made; by authoritarian rather than libertarian methods. He had spoken out against authoritarian socialism in his writings (for example The Conquest of Bread), making the prediction that any state founded on these principles would most likely lead to its breakup and the restoration of capitalism.

He died on February 8, 1921, in the city of Dmitrov, and was buried at the Novodevichy Cemetery. Anarchists marched in his funeral procession carrying banners with anti - Bolshevik slogans, with Lenin's approval. This was the last march by anarchists until 1987, when glasnost saw them hold the first open free protest against Bolshevik state communism for over 60 years in Moscow.

Kropotkin's inspiration has reached into the 20th and 21st centuries as a vision of a new society based on the anarchist principles of anti - statism and anti - authoritarianism, the communist principles of the publicly owned means of production, and his evolutionary theories on the mutual aid between all species and individuals. It is often positioned as a counter to the thinking of Leon Trotsky and Vladimir Lenin, which tended to imply centralized planning and control. To a large degree Kropotkin's emphasis is on local organization, local production obviating the need for central government. Kropotkin's vision is also on agriculture and rural life, making it a contrasting perspective to the largely industrial thinking of communists and socialists.

In his book Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, Kropotkin explored the widespread use of cooperation as a survival mechanism in human societies through their many stages, and animals. He used many real life examples in an attempt to show that the main factor in facilitating evolution is cooperation between individuals in free associated societies and groups, without central control, authority or compulsion. This was in order to counteract the conception of fierce competition as the core of evolution, that provided a rationalization for the dominant political, economic and social theories of the time; and the prevalent interpretations of Darwinism. According to Kirkpatrick Sale:

| “ | With Mutual Aid especially, and later with Fields, Factories, and Workshops, Kropotkin was able to move away from the absurdist limitations of individual anarchism and no - laws anarchism that had flourished during this period and provide instead a vision of communal anarchism, following the models of independent cooperative communities he discovered while developing his theory of mutual aid. It was an anarchism that opposed centralized government and state - level laws as traditional anarchism did, but understood that at a certain small scale, communities and communes and co-ops could flourish and provide humans with a rich material life and wide areas of liberty without centralized control. | ” |

His observations of cooperative tendencies in indigenous peoples, pre - feudal, feudal and those remaining in modern societies, allowed him to conclude that not all human societies were based on competition such as those of industrialized Europe; and that in many societies, cooperation was the norm between individuals and groups. He also concluded that in most pre - industrial and pre - authoritarian societies (where he claimed that leadership, central government and class did not exist) actively defend against the accumulation of private property, for example, by equally sharing out, amongst the community, a person's possessions when he has died; or not allowing a gift to be sold, bartered or used to create wealth.

In another of his books, The Conquest of Bread, Kropotkin proposed a system of economics based on mutual exchanges made in a system of voluntary cooperation. He believed that should a society be socially, culturally, and industrially developed enough to produce all the goods and services required by it, then no obstacle, such as preferential distribution, pricing or monetary exchange will stand as an obstacle for all taking what they need from the social product. He supported the eventual abolition of money or tokens to exchange for goods and services. He further developed these ideas in Fields, Factories and Workshops.

Kropotkin points out what he considers to be the fallacies of the economic systems of feudalism and capitalism, and how he believes they create poverty and scarcity while promoting privilege. He goes on to propose a more decentralized economic system based on mutual aid and voluntary cooperation, asserting that the tendencies for this kind of organization already exist, both in evolution and in human society.

His focus on local production leads to his view that a country should strive for self sufficiency –

manufacture its own goods and grow its own food, lessening dependence

on imports. To these ends he advocated irrigation and growing under

glass to boost local food production ability.

Benjamin Ricketson Tucker (April 17, 1854 – June 22, 1939) was a proponent of American individualist anarchism (which he called "unterrified Jeffersonianism") in the 19th century, and editor and publisher of the individualist anarchist periodical Liberty.

Tucker says that he became an anarchist at the age of 18. Tucker's contribution to American individualist anarchism was as much through his publishing as his own writing. Tucker was the first to translate into English Proudhon's What is Property? and Max Stirner's The Ego and Its Own — which Tucker claimed was his proudest accomplishment. In editing and publishing the anarchist periodical Liberty, he published the original work of Stephen Pearl Andrews, Joshua K. Ingalls, Lysander Spooner, Auberon Herbert, Victor Yarros, and Lillian Harman, daughter of the free love anarchist Moses Harman, as well as his own writing. He also published such items as George Bernard Shaw's first original article to appear in the United States and the first American translated excerpts of Friedrich Nietzsche. In Liberty, Tucker both filtered and integrated the theories of such European thinkers as Herbert Spencer and Pierre - Joseph Proudhon; the economic and legal theories of the American individualists Lysander Spooner, William B. Greene and Josiah Warren; and the writings of the free thought and free love movements in opposition to religiously based legislation and prohibitions on non - invasive behavior. Through these influences Tucker produced a rigorous system of philosophical or individualist anarchism that he called Anarchistic - Socialism, arguing that "[the] most perfect Socialism is possible only on the condition of the most perfect individualism."

According to historian of American individualist anarchism, Frank Brooks, it is easy to misunderstand Tucker's claim of "socialism." Before Marxists established a hegemony over definitions of "socialism, "the term socialism was a broad concept." Tucker (as well as most of the writers and readers in Liberty) understood "socialism" to refer to any of various theories and demands aimed to solve "the labor problem" through radical changes in the capitalist economy; descriptions of the problem, explanations of its causes, and proposed solutions (for example,, abolition of private property, cooperatives, state - ownership, and so on.) varied among "socialist" philosophies. Tucker said socialism was the claim that "labor should be put in possession of its own," holding that what "state socialism" and "anarchistic socialism" had in common was the labor theory of value. However, "Instead of asserting, as did socialist anarchists, that common ownership was the key to eroding differences of economic power," and appealing to social solidarity, Tucker's individualist anarchism advocated distribution of property in an undistorted natural market as a mediator of egoistic impulses and a source of social stability. Tucker said, "the fact that one class of men are dependent for their living upon the sale of their labor, while another class of men are relieved of the necessity of labor by being legally privileged to sell something that is not labor. . . . And to such a state of things I am as much opposed as any one. But the minute you remove privilege. . . every man will be a laborer exchanging with fellow-laborers . . . What Anarchistic - Socialism aims to abolish is usury . . . it wants to deprive capital of its reward."

Tucker first favored a natural rights philosophy where an individual had a right to own the fruits of his labor, then abandoned it in favor of "egoism" influenced by Max Stirner, where he then believed that only the "right of might" exists until overridden by contract.

He objected to all forms of communism, believing that even a

stateless communist society must encroach upon the liberty of

individuals who were in it. He "denounced Marx as the representative of 'the principle of authority which we live to combat.' He thought Proudhon

the superior theorist and the real champion of freedom. 'Marx would

nationalize the productive and distributive forces; Proudhon would

individualize and associate them.'"

Tucker argued that the poor condition of American workers resulted from four legal monopolies based in authority:

- the money monopoly,

- the land monopoly,

- tariffs, and

- patents.

His focus for several decades became the state's economic control of how trade could take place, and what currency counted as legitimate. He saw interest and profit as a form of exploitation made possible by the banking monopoly, which was in turn maintained through coercion and invasion. Any such interest and profit, Tucker called "usury" and he saw it as the basis for the oppression of the workers. In his words, "interest is theft, Rent Robbery, and Profit Only Another Name for Plunder." Tucker believed that usury was immoral; however, he upheld the right for all people to engage in immoral contracts. "Liberty, therefore, must defend the right of individuals to make contracts involving usury, rum, marriage, prostitution, and many other things which are believed to be wrong in principle and opposed to human well being. The right to do wrong involves the essence of all rights."

He asserted that anarchism is meaningless "unless it includes the liberty of the individual to control his product or whatever his product has brought him through exchange in a free market — that is, private property." He acknowledged that "anything is a product upon which human labor has been expended," but would not recognize full property rights to labored - upon land: "It should be noted, however, that in the case of land, or of any other material the supply of which is so limited that all cannot hold it in unlimited quantities, Anarchism undertakes to protect no titles except such as are based upon actual occupancy and use." Tucker opposed title to land that was not in use, arguing that an individual would have to use land continually in order to retain exclusive right to it. If this practice is not followed, he believed it results in a "land monopoly."

Tucker also opposed state protection of the banking monopoly, the requirement that one must obtain a charter to engage in the business of banking. He hoped to raise wages by deregulating the banking industry, reasoning that competition in banking would drive down interest rates and stimulate entrepreneurship. Tucker believed this would decrease the proportion of individuals seeking employment and therefore wages would be driven up by competing employers. "Thus, the same blow that strikes interest down will send wages up." He did not oppose individuals being employed by others, but due to his interpretation of the labor theory of value, he believed that in the present economy individuals do not receive a wage that fully compensates them for their labor. He wrote that if the four "monopolies" were ended, "it will make no difference whether men work for themselves, or are employed, or employ others. In any case they can get nothing but that wages for their labor which free competition determines."

Tucker opposed protectionism, believing that tariffs cause high prices by preventing national producers from having to compete with foreign competitors. He believed that free trade would help keep prices low and therefore would assist laborers in receiving their "natural wage." Tucker did not believe in a right to intellectual property in the form of patents, on the grounds that patents and copyrights protect something which cannot rightfully be held as property. In "The Attitude of Anarchism toward Industrial Combinations," he wrote that the basis for property is "the fact that it is impossible in the nature of things for concrete objects to be used in different places at the same time." Property in concrete things is "socially necessary." "[S]ince successful society rests on individual initiative, [it is necessary] to protect the individual creator in the use of his concrete creations by forbidding others to use them without his consent." Because ideas are not concrete things, they cannot be held and protected as property. Ideas can be used in different places at the same time, and so their use should not be restricted by patents. This was a source of conflict with the philosophy of fellow individualist Lysander Spooner who saw ideas as the product of "intellectual labor" and therefore private property.

According to Victor Yarros:

He [Tucker] opposed savagely any and all reform movements that had paternalistic aims and looked to the state for aid and fulfillment... For the same reason, consistent, unrelenting opposition to compulsion, he combated "populism," "greenbackism," the single - tax movement, and all forms of socialism and communism. He denounced and exposed Johann Most, the editor of Freiheit, the anarchist - communist organ. The end, he declared, could never justify the means, if the means were intrinsically immoral — and force, by whomsoever used, was immoral except as a means of preventing or punishing aggression.

Tucker rejected the legislative programs of labor unions, laws imposing a short day, minimum wage laws, forcing businesses to provide insurance to employees, and compulsory pension systems. He believed instead that strikes should be composed by free workers rather than by bureaucratic union officials and organizations. He argued, "strikes, whenever and wherever inaugurated, deserve encouragement from all the friends of labor. . . They show that people are beginning to know their rights, and knowing, dare to maintain them." and furthermore, "as an awakening agent, as an agitating force, the beneficent influence of a strike is immeasurable. . . with our present economic system almost every strike is just. For what is justice in production and distribution? That labor, which creates all, shall have all." Tucker envisioned an individualist anarchist society as "each man reaping the fruits of his labor and no man able to live in idleness on an income from capital.... become[ing] a great hive of Anarchistic workers, prosperous and free individuals [combining] to carry on their production and distribution on the cost principle." rather than a bureaucratic organization of workers organized into rank and file unions. However, he did hold a genuine appreciation for labor unions (which he called "trades - union socialism") and saw it as "an intelligent and self - governing socialism" saying, "[they] promise the coming substitution of industrial socialism for usurping legislative mobism."

Tucker's concept of the four monopolies has recently been discussed by Kevin Carson in his book Studies in Mutualist Political Economy. Carson incorporates the idea into his thesis that the exploitation of labor is only possible due to state intervention, however, he argues that Tucker failed to notice a fifth form of privilege: transportation subsidies.

One form of contemporary government intervention that Tucker almost entirely ignored was transportation subsidies. This seems odd at first glance, since "internal improvements" had been a controversial issue throughout the 19th century, and were a central part of the mercantilist agenda of the Whigs and the Gilded Age GOP. Indeed, Lincoln has announced the beginning of his career with a "short but sweet" embrace of Henry Clay's program: a national bank, a high tariff, and internal improvements. This neglect, however, was in keeping with Tucker's inclination. He was concerned with privilege primarily as it promoted monopoly profits through unfair exchange at the individual level, and not as it affected the overall structure of production. The kind of government intervention that James O'Connor was later to write about, that promoted accumulation and concentration by directly subsidizing the operating costs of big business, largely escaped his notice.

Carson believes that Tucker's four monopolies and transportation subsidies created the foundation for the monopoly capitalism and military - industrial complex of the 20th century.

Tucker did not have a Utopian vision of anarchy where individuals would not coerce others.

He advocated that liberty and property be defended by private

institutions. Opposing the monopoly of the state in providing security,

he advocated a free market of competing defense providers, saying

"defense is a service like any other service; ... it is labor both

useful and desired, and therefore an economic commodity subject to the

law of supply and demand."

He said that anarchism "does not exclude prisons, officials, military,

or other symbols of force. It merely demands that non - invasive men shall

not be made the victims of such force. Anarchism is not the reign of

love, but the reign of justice. It does not signify the abolition of

force - symbols but the application of force to real invaders."

Tucker expressed that the market based providers of security would

offer protection of land that was being used, and would not offer

assistance to those attempting to collect rent: "The land for the people' . . . means the protection by . . . voluntary associations for

the maintenance of justice . . . of all people who desire to cultivate

land in possession of whatever land they personally cultivate . . . and

the positive refusal of the protecting power to lend its aid to the

collection of any rent, whatsoever."

Tucker abandoned natural rights doctrine and became a proponent of what is known as "Egoism." This led to a split in American Individualism between the growing number of Egoists and the contemporary Spoonerian "Natural Lawyers". Tucker came to hold the position that no rights exist until they are created by contract. This led him to controversial positions such as claiming that infants had no rights and were the property of their parents, because they did not have the ability to contract. He said that a person who physically tries to stop a mother from throwing her "baby into the fire" should be punished for violating her property rights. He said that children would shed their status as property when they became old enough to contract "to buy or sell a house" for example, noting that the precocity varies by age and would be determined by a jury in the case of a complaint.

He also came to believe that aggression towards others was justifiable if doing so led to a greater decrease in "aggregate pain" than refraining from doing so. He said:

the ultimate end of human endeavor is the minimum of pain. We aim to decrease invasion only because, as a rule, invasion increases the total of pain (meaning, of course, pain suffered by the ego, whether directly or through sympathy with others). But it is precisely my contention that this rule, despite the immense importance which I place upon it, is not absolute; that, on the contrary, there are exceptional cases where invasion -- that is, coercion of the non - invasive -- lessens the aggregate pain. Therefore coercion of the non - invasive, when justifiable at all, is to be justified on the ground that it secures, not a minimum of invasion, but a minimum of pain. . . . [T]o me [it is] axiomatic -- that the ultimate end is the minimum of pain

Tucker now said that there were only two rights, "the right of might"

and "the right of contract." He also said, after converting to Egoist

individualism that ownership in land is legitimately transferred through

force unless contracted otherwise. In 1892, he said "In times past... it

was my habit to talk glibly of the right of man to land. It was a bad

habit, and I long ago sloughed it off. Man's only right to land is his

might over it. If his neighbor is mightier than he and takes the land

from him, then the land is his neighbor's, until the latter is

dispossessed by one mightier still." However, he said he believed that individuals would come to the realization that "equal liberty"

and "occupancy and use" doctrines were "generally trustworthy guiding

principle of action," and, as a result, they would likely find it in

their interests to contract with each other to refrain from infringing

upon equal liberty and from protecting land that was not in use.

Though he believed that non - invasion, and "occupancy and use as the

title to land" were general rules that people would find in their own

interests to create through contract, he said that these rules "must be

sometimes trodden underfoot."

In 1908, a fire destroyed Tucker's uninsured printing equipment and his 30 year stock of books and pamphlets. Tucker's lover, Pearl Johnson — 25 years his junior — was pregnant with their daughter, Oriole Tucker. Six weeks after Oriole's birth, Tucker closed both Liberty and the book shop and retired with his family to France. In 1913, he came out of retirement for two years to contribute articles and letters to The New Freewoman which he called "the most important publication in existence."

Late in life, Tucker became much more pessimistic about the prospects for anarchism. In 1926, Vanguard Press published a selection of his writings entitled Individual Liberty, in which Tucker added a postscript to "State Socialism and Anarchism", which stated "Forty years ago, when the foregoing essay was written, the denial of competition had not yet effected the enormous concentration of wealth that now so gravely threatens social order. It was not yet too late to stem the current of accumulation by a reversal of the policy of monopoly. The Anarchistic remedy was still applicable." But, Tucker argued, "Today the way is not so clear. The four monopolies, unhindered, have made possible the modern development of the trust, and the trust is now a monster which I fear, even the freest banking, could it be instituted, would be unable to destroy. ... If this be true, then monopoly, which can be controlled permanently only for economic forces, has passed for the moment beyond their reach, and must be grappled with for a time solely by forces political or revolutionary. Until measures of forcible confiscation, through the State or in defiance of it, shall have abolished the concentrations that monopoly has created, the economic solution proposed by Anarchism and outlined in the forgoing pages – and there is no other solution – will remain a thing to be taught to the rising generation, that conditions may be favorable to its application after the great leveling. But education is a slow process, and may not come too quickly. Anarchists who endeavor to hasten it by joining in the propaganda of State Socialism or revolution make a sad mistake indeed. They help to so force the march of events that the people will not have time to find out, by the study of their experience, that their troubles have been due to the rejection of competition."

By 1930, Tucker had concluded that centralization and advancing technology had doomed both anarchy and civilization. "The matter of my famous 'Postscript' now sinks into insignificance; the insurmountable obstacle to the realization of Anarchy is no longer the power of the trusts, but the indisputable fact that our civilization is in its death throes. We may last a couple of centuries yet; on the other hand, a decade may precipitate our finish. ... The dark ages sure enough. The Monster, Mechanism, is devouring mankind."

According to James Martin, when referring to the world scene of the mid 1930s in private correspondence, Tucker wrote: "Capitalism is at least tolerable, which cannot be said of Socialism or Communism" and went on to observe that, "under any of these regimes a sufficiently shrewd man can feather his nest.". Susan Love Brown claims that this unpublished, private letter, which does not distinguish between the anarchist socialism Tucker advocated and the state socialism he criticized, served in "providing the shift further illuminated in the 1970s by anarcho - capitalists."

Tucker died in Monaco

in 1939, in the company of his family. His daughter, Oriole, reported,

"Father's attitude towards communism never changed one whit, nor about

religion.... In his last months he called in the French housekeeper. 'I

want her,' he said, 'to be a witness that on my death bed I'm not

recanting. I do not believe in God!"

Born April 17, 1854 in South Dartmouth, Massachusetts.

- 1872, age 18 — While a student at M.I.T., Tucker attended a convention of the New England Labor Reform League in Boston, chaired by William B. Greene, author of Mutual Banking (1850). At the convention, Tucker purchased Mutual Banking, True Civilization, and a set of Ezra Heywood's pamphlets. Furthermore, Free - love anarchist, Ezra Heywood introduced Tucker to William B. Greene and Josiah Warren, author of True Civilization (1869). He also started a relationship with Victoria Woodhull at this time, lasting for 3 years.

- 1876, age 22 — Tucker's debut into radical circles: Heywood published Tucker's English translation of Proudhon's classic work What is Property?.

- 1877 - 1878, age 23 - 24 — Published his original journal, Radical Review, which lasted four issues.

- August 1881 to April 1908, age 27 to 54 — published the periodical, Liberty, "widely considered to be the finest individualist - anarchist periodical ever issued in the English language."

- 1892, age 38 — moved Liberty from Boston to New York

- 1906, age 52 — Opened Tucker's Unique Book Shop in New York City — promoting "Egoism in Philosophy, Anarchism in Politics, Iconoclasm in Art".

- 1908, age 54 — A fire destroyed Tucker's uninsured printing equipment and his 30 year stock of books and pamphlets. Tucker's lover, Pearl Johnson — 25 years his junior — was pregnant with their daughter, Oriole Tucker. Six weeks after Oriole's birth, Tucker closed both Liberty and the book shop and moved his family to France.

- 1913, age 59 — Tucker comes out of retirement for two years to contribute articles and letters to The New Freewoman which he called "the most important publication in existence"

- 1939, age 85 — Tucker died in Monaco, in the company of his lover Pearl Johnson and their daughter, Oriole, who reported, "Father's attitude towards communism never changed one whit, nor about religion.... In his last months he called in the French housekeeper. 'I want her,' he said, 'to be a witness that on my death bed I'm not recanting. I do not believe in God!"