<Back to Index>

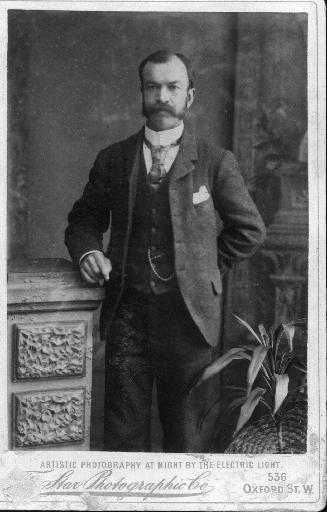

- Inventor Edward Butler, 1862

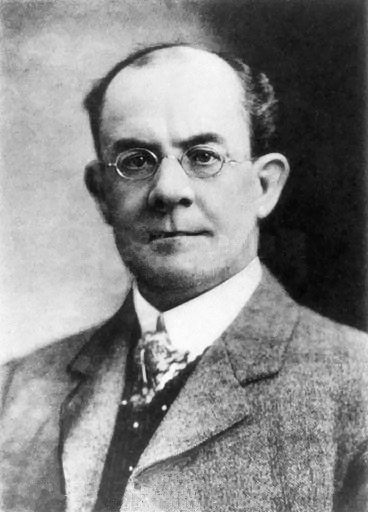

- Inventor Hertbert Akroyd - Stuart, 1864

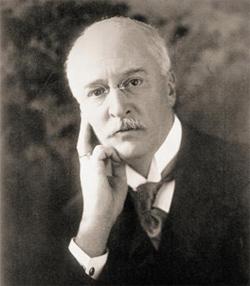

- Inventor and Engineer Rudolf Christian Karl Diesel, 1858

PAGE SPONSOR

Edward Butler (1862, England - 1940) was an English inventor who produced an early three - wheeled automobile, called the Butler Petrol Cycle, which is accepted by many as the first British car.

Butler showed plans for his three - wheeled vehicle at the Stanley Cycle Show in London in 1884, two years earlier than Karl Benz, who is generally recognized as the inventor of the modern automobile.

Butler's vehicle was also the first design to be shown at the 1885

Inventions Exhibition, also in London.

Built by the Merryweather Fire Engine company in Greenwich, in 1888, the Butler Petrol Cycle (first recorded use of the term) was a three - wheeled vehicle, with the rear wheel directly driven by a 5/8 hp (466W) 600 cc (40 in3; 2¼ × 5 inch {57 × 127 mm}) flat twin four stroke engine (with magneto ignition replaced by coil and battery), equipped with rotary valves and a float - fed carburetor (five years before Maybach), and Ackermann steering, all of which were state of the art at the time. Starting was by compressed air. The engine was liquid cooled, with a radiator over the rear driving wheel. Speed was controlled by means of a throttle valve lever. No braking system was fitted; the vehicle was stopped by raising and lowering the rear driving wheel using a foot operated lever; the weight of the machine was then borne by two small castor wheels. The driver was seated between the front wheels.

The vehicle featured in an article in the 14 February 1891 issue of Scientific American, where it was stated that one gallon of fuel in the form of petroleum or benzolene could propel the vehicle for forty miles (5.9 L / 100 km) at a speed of 3 - 10 mph (5 – 16 km/h).

Butler improved the specifications of his vehicle over the years, but was prevented from adequately testing it due to the 1865 Red Flag Act, which legislated a maximum speed for self propelled road vehicles of 2 mph (3 km/h) in built up areas and 4 mph (6.5 km/h) in rural areas. Additionally, the vehicle had to be attended by three people, one of which had to proceed in front of the vehicle waving a red flag.

Butler wrote in the magazine The English Mechanic in 1890, "The authorities do not countenance its use on the roads, and I have abandoned in consequence any further development of it."

Due to general lack of interest, Butler broke up his machine for scrap in 1896, and sold the patent rights to Harry J. Lawson who continued manufacture of the engine for use in motorboats.

Instead, Butler turned to making stationary and marine engines. His motor tricycle was in advance of its better known contemporaries on several points.

Herbert Akroyd - Stuart (28 January 1864, Halifax Yorkshire, England - 19 February 1927, Halifax) was an English inventor who is noted for his invention of the hot bulb engine, or heavy oil engine.

Akroyd - Stuart had lived in Australia in his early years. He was educated at Newbury Grammar School (now St. Bartholomew's School) and Finsbury Technical College on Cowper Street. He was the son of Charles Stuart, founder of the Bletchley Iron and Tinplate Works, and joined his father in the business in 1887.

In 1885 Akroyd Stuart accidentally spilt paraffin oil (kerosene) into a pot of molten tin. The paraffin oil vaporized and caught fire when in contact with a paraffin lamp. This gave him an idea to pursue the possibility of using paraffin oil (very similar to modern day diesel) for an engine, which unlike petrol would be difficult to be vaporized in a carburetor as its volatility is not sufficient to allow this.

His first prototype engines were built in 1886. In 1890, in collaboration with Charles Richard Binney, he filed Patent 7146 for Richard Hornsby and Sons of Grantham, Lincolnshire, England. The patent was entitled: "Improvements in Engines Operated by the Explosion of Mixtures of Combustible Vapour or Gas and Air".

One such engine was sold to Newport Sanitary Authority, but the

compression ratio was too low to get it started from cold, and it needed

a heat poultice to get it going.

Akroyd - Stuart's engines were built from 26 June 1891 by Richard Hornsby and Sons as the Hornsby Akroyd Patent Oil Engine under license and were first sold commercially on 8 July 1892. It was the first internal combustion engine to use a pressurized fuel injection system.

The Hornsby - Akroyd engine used a comparatively low compression ratio, so that the temperature of the air compressed in the combustion chamber at the end of the compression stroke was not high enough to initiate combustion. Combustion instead took place in a separated combustion chamber, the "vaporizer" (also called the "hot bulb") mounted on the cylinder head, into which fuel was sprayed. It was connected to the cylinder by a narrow passage and was heated either by the cylinder's coolant or by exhaust gases while running; an external flame such as a blowtorch was used for starting. Self ignition occurred from contact between the fuel - air mixture and the hot walls of the vaporizer. By contracting the bulb to a very narrow neck where it attached to the cylinder, a high degree of turbulence was set up as the ignited gases flashed through the neck into the cylinder, where combustion was completed. As the engine's load increased, so did the temperature of the bulb, causing the ignition period to advance; to counteract pre-ignition, water was dripped into the air intake.

Hot bulb engines were produced until the late 1920s, often being called "semi - diesels", even though they were not as efficient as compression ignition engines. They had the advantage of comparative simplicity, since they did not require the air compressor used by early Diesel engines; fuel was injected mechanically (solid injection) near the start of the compression stroke, at a much lower pressure than that of Diesel engines.

Richard Hornsby and Sons built the world's first oil engined railway locomotive LACHESIS for the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich, England, in 1896. They also built the first compression - ignition powered automobile.

Similar engines were built by Bolinder in Sweden and some of these still survive in canal boats.

Hot bulb engines were built in the USA by the De La Vergne Company of New York, later the New York Refrigerating Company - inventing the modern refrigerator in 1930, who purchased a license in 1893.

The modern Diesel engine is a hybrid incorporating the features of direct (airless) injection and compression - ignition, both patented (No. 7146) as Improvements in Engines Operated by the Explosion of Mixtures of Combustible Vapour or Gas and Air by Akroyd - Stuart and Charles Richard Binney in May 1890. Another patent (No. 15,994) was taken out on 8 October 1890, which details the working of a complete engine, essentially that of a diesel engine where air and fuel are introduced separately.

Rudolf Diesel patented compression - ignition in 1892; his injection system, where combustion was produced isobarically (the technique having been patented by George Brayton in 1874 for his carburetor), was not subsumed into later engines, Akroyd - Stuart's injection system with isochoric combustion developed at Hornsbys being preferred.

Akroyd - Stuart's compression ignition engine (as opposed to spark ignition) was patented two years earlier than Diesel's similar engine; Diesel's only patentable idea was to increase the pressure. The hot bulb engine, due to the lower pressures used (around 90 PSI) as opposed to the Diesel engine's c. 500 PSI, had only about a 12% thermal efficiency.

In 1892, Akroyd - Stuart patented a water - jacketed vaporizer to allow compression ratios to be increased. In the same year, Thomas Henry Barton (who later founded Barton Transport) at Hornsbys built a working high compression version for experimental purposes whereby the vaporizer was replaced with a cylinder head therefore not relying on air being preheated, but by combustion through higher compression ratios. It ran for six hours - the first time automatic ignition was produced by compression alone. This was five years before Rudolf Diesel built his well known high compression prototype engine in 1897.

Diesel was, however, subsequently credited with the innovation despite the adduced evidence to the contrary.

In 1900, he moved to Australia and set up a company Sanders & Stuart with his brother Charles, latterly moving back to Yorkshire, England. He died of throat cancer and was buried in All Souls church in Boothtown, Halifax.

The University of Nottingham has hosted the Akroyd - Stuart Memorial Lecture on occasional years in his memory since 1928. One was presented by Sir Frank Whittle in 1946. Akroyd Stuart had worked with Professor William Robinson in the late 19th century, who was professor of engineering from 1890 to 1924 at University College Nottingham.

Akroyd - Stuart also left money to the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Royal Aeronautical Society and Institute of Marine Engineering, which provided for their respective bi-annual Akroyd - Stuart Prizes.

Rudolf Christian Karl Diesel (March 18, 1858 – September 29, 1913) was a German inventor and mechanical engineer, famous for the invention of the diesel engine.

Diesel was born in Paris, France in 1858, the second of three children of Elise (neé Strobel) and Theodor Diesel. His parents were Bavarian immigrants living in Paris. Theodor Diesel, a bookbinder by trade, left his home town of Augsburg, Bavaria, in 1848. He met his wife, a daughter of a Nuremberg merchant, in Paris in 1855 and became a leather goods manufacturer there.

Rudolf Diesel spent his early childhood in France, but as a result of the outbreak of the Franco - Prussian War in 1870, his family (as were many other Germans) was forced to leave. They settled in London. Before the war's end in 1871, however, Diesel's mother sent 12 year old Rudolf to Augsburg to live with his aunt and uncle, Barbara and Christoph Barnickel, to become fluent in German and to visit the Königliche Kreis - Gewerbsschule (Royal County Trade School), where his uncle taught mathematics.

At age 14, Rudolf wrote a letter to his parents stating that he wanted to become an engineer. After finishing his basic education at the top of his class in 1873, he enrolled at the newly founded Industrial School of Augsburg. Two years later, he received a merit scholarship from the Royal Bavarian Polytechnic of Munich, which he accepted against the wishes of his parents, who would rather have seen him start to work.

One of his professors in Munich was Carl von Linde. Diesel was unable to be graduated with his class in July 1879 because he fell ill with typhoid. While waiting for the next examination date, he gained practical engineering experience at the Gebrüder Sulzer Maschinenfabrik (Sulzer Brothers Machine Works) in Winterthur, Switzerland. Diesel was graduated in January 1880 with highest academic honors and returned to Paris, where he assisted his former Munich professor, Carl von Linde, with the design and construction of a modern refrigeration and ice plant. Diesel became the director of the plant one year later.

In 1883, Diesel married Martha Flasche, and continued to work for Linde, gaining numerous patents in both Germany and France.

In early 1890, Diesel moved to Berlin with his wife and children, Rudolf Jr, Heddy, and Eugen, to assume management of Linde's corporate research and development department and to join several other corporate boards there. As he was not allowed to use the patents he developed while an employee of Linde's for his own purposes, he expanded beyond the field of refrigeration. He first worked with steam, his research into thermal efficiency and fuel efficiency leading him to build a steam engine using ammonia vapor. During tests, however, the engine exploded and almost killed him. He spent many months in a hospital, followed by health and eyesight problems. He then began designing an engine based on the Carnot cycle, and in 1893, soon after Karl Benz was granted a patent for his invention of the motor car in 1886, Diesel published a treatise entitled Theorie und Konstruktion eines rationellen Wärmemotors zum Ersatz der Dampfmaschine und der heute bekannten Verbrennungsmotoren [Theory and Construction of a Rational Heat - engine to Replace the Steam Engine and Combustion Engines Known Today] and formed the basis for his work on and invention of, the diesel engine.

Diesel understood thermodynamics and the theoretical and practical constraints on fuel efficiency. He knew that as much as 90% of the energy available in the fuel is wasted in a steam engine. His work in engine design was driven by the goal of much higher efficiency ratios. After experimenting with a Carnot Cycle engine, he developed his own approach. Eventually he obtained a patent for his design for a compression ignition engine. In his engine, fuel was injected at the end of compression and the fuel was ignited by the high temperature resulting from compression. From 1893 to 1897, Heinrich von Buz, director of MAN AG in Augsburg, gave Rudolf Diesel the opportunity to test and develop his ideas. Rudolf Diesel obtained patents for his design in Germany and other countries, including the USAIn the evening of 29 September 1913, Diesel boarded the post office steamer Dresden in Antwerp on his way to a meeting of the Consolidated Diesel Manufacturing company in London. He took dinner on board the ship and then retired to his cabin at about 10 p.m., leaving word for him to be called the next morning at 6:15 a.m. His cabin was found empty during a roll call and he was never seen alive again. Ten days later, the crew of the Dutch boat Coertsen came upon the corpse of a man floating in the ocean. The body was in such an advanced state of decomposition that it was unrecognizable and they did not bring it aboard. Instead, the crew retrieved personal items (pill case, wallet, pocket knife, eyeglass case) from the clothing of the dead man, and returned the body to the sea. On 13 October these items were identified by Rudolf's son, Eugen Diesel, as belonging to his father.

There are various theories to explain Diesel's death. His biographers, such as Grosser (1978), present a case for suicide, and clearly consider it most likely. Conspiracy theories

suggest that various people's business or military interests may have

provided motives for homicide, however. Evidence is limited for all

explanations.

After Diesel's death, the diesel engine underwent much development and became a very important replacement for the steam piston engine in many applications. Because the diesel engine required a heavier, more robust construction than a gasoline engine, it was not widely used in aviation. The diesel engine became widespread in many other applications, however, such as stationary engines, submarines, ships, and much later, locomotives, trucks, and in modern automobiles. Diesel engines are most often found in applications where a high torque requirement and low RPM requirement exist. Because of their generally more robust construction and high torque, diesel engines have also become the workhorses of the trucking industry. Recently, diesel engines that have overcome their weight penalty have been designed, certified, and flown in light aircraft. These engines are designed to run on either diesel fuel or more commonly jet fuel.

The diesel engine has the benefit of running more fuel efficiently

than gasoline engines due to much higher compression ratios and longer

duration of combustion, which means the temperature rises more slowly,

allowing more heat to be converted to mechanical work. Diesel was

interested in using coal dust or vegetable oil as fuel, and in fact, his engine was run on peanut oil. Although these fuels were not immediately popular, during 2008 rises in fuel prices, coupled with concerns about oil reserves, have led to more widespread use of vegetable oil and biodiesel. The primary source of fuel remains what became known as diesel fuel, an oil byproduct derived from refinement of petroleum.

Akroyd - Stuart's compression ignition engine (as opposed to spark ignition) was patented two years earlier than Diesel's similar engine; Diesel's patentable idea was to increase the pressure. Due to the lower pressures used, the hot bulb engine, with an internal pressure of about 90 PSI, as opposed to the Diesel engine's c. 500 PSI, had only about a 12% thermal efficiency versus more than 50% for some large Diesels. Details of the claim that a patent submitted by Herbert Akroyd Stuart has pre-dated that of Rudolf Diesel may be found in his biography.

The high compression and thermal efficiency is what distinguishes the patent granted to Diesel from a hot bulb engine patent.