<Back to Index>

- Engineer and Inventor Karl Gustaf Patrik de Laval, 1845

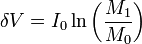

- Entrepreneur Emil Jellinek - Mercedes, 1853

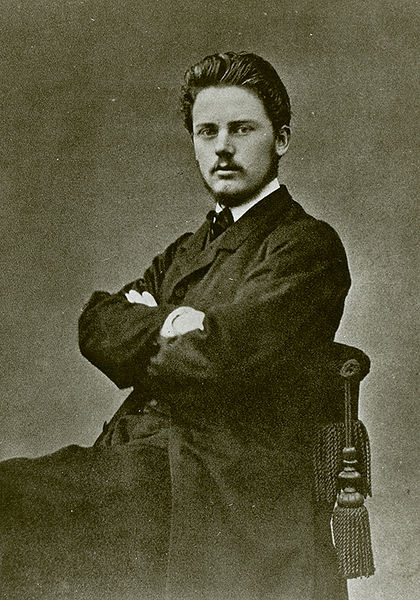

- Rocket Scientist Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovsky, 1857

PAGE SPONSOR

Karl Gustaf Patrik de Laval (May 9, 1845 - February 2, 1913) was a Swedish engineer and inventor who made important contributions to the design of steam turbines and, more importantly, dairy machinery.

De Laval was born at Orsa in Dalarna. He enrolled at the Institute of Technology in Stockholm (later the Royal Institute of Technology) in 1863, receiving a degree in mechanical engineering in 1866, after which he matriculated at Uppsala University in 1867. He was then employed by the Swedish mining company, Stora Kopparberg. From there he returned to Uppsala University and completed his doctorate in 1872. He was further employed in Kloster Iron works in Germany. Gustaf de Laval was a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences from 1886. He was a successful engineer and businessman. He also held the national office, being elected to Swedish parliament, from 1888 – 1890 and later became a member of the senate. De Laval died in Stockholm in 1912 at the age of 67.

In 1882 he introduced his concept of an impulse steam turbine and in 1887 built a small steam turbine to demonstrate that such devices could be constructed on that scale. In 1890 Laval developed a nozzle to increase the steam jet to supersonic speed, working off the kinetic energy of the steam, rather than its pressure. The nozzle, now known as a de Laval nozzle, is used in modern rocket engine nozzles. De Laval turbines can run at up to 30,000 rpm. The turbine wheel was mounted on a long flexible shaft, its two bearings spaced far apart on either side. Since the wheel could not be perfectly balanced, this allowed it to spin slightly out of true, without breaking the bearings. The higher speed of the turbine demanded that he also designed new approaches to reduction gearing, which are still in use today. Since the materials available at the time were not strong enough for the immense centrifugal forces, the output from the turbine was limited and large scale electric steam generators were dominated by designs using the alternative compound steam turbine approach of Charles Parsons.

Using high pressure steam in a turbine that had oil fed bearings

meant that some of the steam contaminated the lube oil, and as a result,

perfecting commercial steam turbines required that he also develop an

effective oil / water separator. After trying several methods, he

concluded that a centrifugal separator was the most affordable and

effective method. He developed several types, and their success

established the centrifugal separator as a useful device in a variety of

applications.

De Laval also made important contributions to the dairy industry, including the first centrifugal milk - cream separator and early milking machines, the first of which he patented in 1894. It was not until after his death, however, that the company he founded marketed the first commercially practical milking machine, in 1918. Together with Oscar Lamm, de Laval founded the company Alfa Laval in 1883, which was known as AB Separator until 1963 when the present name was introduced.

In 1991, Alfa Laval Agri, a company producing dairy and farming

machinery was split from Alfa Laval when it was bought by the Tetra Pak

Group. When Alfa Laval was sold, Alfa Laval Agri remained a part of the

Tetra Pak group and was renamed DeLaval, after the company's founder.

Emil Jellinek, known after 1903 as Emil Jellinek - Mercedes (6 April 1853 – 21 January 1918) was a wealthy European entrepreneur who sat on the board of Daimler - Motoren - Gesellschaft ('DMG') between 1900 and 1909. He specified an engine designed there by Wilhelm Maybach and Gottlieb Daimler for the first 'modern' car. Jellinek required naming the engine after his daughter, Mercedes Jellinek. The Mercedes 35hp model later contributed to the brand name developed in 1926, Mercedes - Benz, when DMG and Benz & Cie. merged into what is now among the largest car brands in the world. Jellinek lived in Vienna, Austria but later moved to Nice on the French Riviera, where he was the General Consul to Austria - Hungary.

Jellinek was born in Leipzig, Germany, the son of Dr Adolf Jellinek (sometimes known also as Aaron Jellinek). His father was a well known Czech - Hungarian rabbi and intellectual in the Jewish collective around Leipzig and Vienna. Jellinek's mother Rosalie Bettelheim (born 1832 in Budapest, died 1892 in Baden bei Wien) was an active rebbitzen. He had two brothers, both of whom achieved fame: Max Hermann Jellinek as a linguist, and Georg Jellinek as an international law teacher. His sisters were Charlotte and Pauline.

The family moved, shortly after Jellinek's birth, to Vienna. He found

paying attention to school work difficult and dropped out of several

schools including Sonderhausen. His parents were displeased with his

performance, while Jellinek began to indulge in practical jokes. In

1870, when he was 17, his parents found him a job as a clerk in a Moravian

railway company, Rot - Koestelec North - Western. Jellinek lasted two years

at this company before being sacked when the management discovered that

he had been organizing train races late at night.

In 1872, when 19 years old, he moved to France. There, through his father's connections, Schmidl, the Austro - Hungarian Consul in Morocco, requested his services getting Jellinek diplomatic posts at Tangier and Tetouan successively. In Tetouan he met Rachel Goggmann Cenrobert an African born lady of French - Sepharadi descent.

In 1874 he was called up for military service in Vienna but was declared unfit. He resumed his diplomatic career as Austrian vice - consul at Oran, Algeria, and also began trading Algerian grown tobacco to Europe in partnership with Rachel's father.

He also worked as an inspector for the French Aigle insurance

company and traveled to Vienna briefly in 1881 at the age of 28 to open

one of its branch offices. Returning to Oran, he finally married

Rachel, and their first two sons Adolph and Fernand were born there.

Two years later in 1884, Jellinek joined the insurance company full time and moved with the family to Baden bei Wien, Austria, where they lived in the house of a wine dealer named Hanni. In Baden in 1889 his first daughter, Adrienne Manuela Ramona Jellinek, was born on September 16, and called Mercédès, the name Mercédès meaning "gifts" or "favors" in Spanish. Rachel died 4 years after the birth of her daughter. Even so, Jellinek came to believe the name Mercedes brought good fortune and called all his properties after it. One of his sons wrote: “He was as superstitious as the ancient Romans.”

Jellinek's insurance business and stock market trading became very successful, and they started to spend the winters in Nice on the fashionable French Riviera, eventually moving there and establishing links with both international business people and the local aristocracy.

It was in Nice that Jellinek became enthralled by the automobile, studying any information that he could gather about it and purchasing successively: a De Dion - Bouton, a Léon - Bollée Voiturette, both tricycles, and a four seat Benz motorized coach.

Helped by his diplomatic career, he became the Austrian Consul General in Nice, Jellinek began selling automobiles, mainly French makes, to European aristocrats spending winter vacations in the region. Associated with the automobile business were Leon Desjoyeaux, from Nice, and C. L. “Charley” Lehmann, from Paris. He acquired a large mansion which he named Villa Mercedes to run the business from and by 1897 he was selling about 140 cars a year and started calling them Mercedes. The car business was by now more profitable than his insurance work.

Rachel died in 1893 and was buried in Nice. In 1899 he married again

to Madelaine Henriette Engler (Anaise Jellinek), and had four more

children Alain Didier, Guy, Rene and Andree (Maya).

Seeing an advertisement for a DMG car in the weekly magazine Fliegende Blätter, Jellinek now aged 43 traveled to Cannstatt, Stuttgart, in 1896 to find out more about the company and its factory and the designers Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach. He placed an order for one of the Daimler cars which was delivered in October of that year.

The car was a Phoenix Double - Phaeton with 8 hp engine and capable of reaching 24 km/h (15 mph). Maybach had designed the DMG - Phoenix engine, which featured four cylinders for the first time in a car, in 1894 when staying at Stuttgart's former Hermann Hotel.

DMG seemed a reliable enterprise, so Jellinek decided to start selling its cars. In 1898 he wrote to DMG requesting six more cars and to become a DMG main agent and distributor. In 1899 he sold 10 cars and in 1900 29. As well as French car makers such as Peugeot and Panhard & Levassor and other makers licensed to sell Daimler engined vehicles in France, there was a shortage of cars and Jellinek benefited by being able to beat other suppliers lengthy waiting times.

Jellinek kept contacting DMG's designers with his ideas, some good but often with harangues such as: "Your manure wagon has just broken down on schedule", "Your car is a cocoon and I want the butterfly" or "Your engineers should be locked up in an insane asylum." This annoyed Daimler but Maybach took notice of many of his suggestions.

Every year in March, the French Riviera celebrated a speed week, attracting many of the local high society.

The events included:

- Nice-Castellane 90 km event (long distance race)

- Magagnosc event (touring race)

- Promenade des Anglais (sprint race)

- Nice - La Turbie (hill climb race)

- Monte Carlo (Concours d'elegance)

In 1899 Jellinek entered his cars in all of them. As the usage of pseudonyms was common, he called his race team Mercedes and this was visibly written on the cars' chassis. Monsieur Mercedes became his personal alias and he became well known by it in the region.

Using the DMG - Phoenix, Jellinek easily won all the races, reaching 35 km/h (22 mph), but he was still not satisfied with the car.

In 1899 DMG commissioned some engineers including Wilhelm Bauer, Wilhelm Werner and Hermann Braun, to investigate the possibility of using the Phoenix for sporting events as at that time car racing was the best way of generating publicity in Europe.

On March 30, 1900 Wilhelm Bauer decided spontaneously to enter the Nice - La Turbie hill climb but crashed fatally after hitting a rock on the first turn while avoiding spectators. This caused DMG to abandon racing.

Nonetheless, Jellinek came to an agreement with DMG on April 2, 1900 by promising the large sum of 550,000 Goldmark if Wilhelm Maybach would design a revolutionary sports car for him, to be called the Mercedes, of which 36 units had to be delivered before October 15. The deal also included an order for 36 standard DMG 8 hp cars. Jellinek also became a member of DMG 's Board of Management and obtained the exclusive dealership for the new Mercedes for France, Austria, Hungary, Belgium and United States of America. Jellinek had some legal problems over the use of the Daimler name in France with Panhard Levassor who owned the Daimler licenses for France, and the use of the Mercedes name put an end to that problem.

Jellinek laid down a strict specification for the Mercedes stating "I don't want a car for today or tomorrow, it will be the car of the day after tomorrow". He itemized many new parameters to overcome the problems found in many of the ill designed "horseless carriages" of the time which made them unsuitable for high speeds and at risk of overturning:

- Long wheelbase and wide track to provide stability.

- Engine to be better located on the car's chassis.

- Lower center of gravity.

- Electric ignition using the new Bosch system (in lieu of a gas heated glow tube).

The model would be officially called the Daimler - Mercedes which the DMG chairman accepted readily as it overcame the problem of the Daimler name in France being owned by Panhard & Levassor.

Over the next few months, Jellinek oversaw the development of the new car at first by daily telegrams and later by traveling to Stuttgart. He took delivery of the first one on December 22, 1900, at Nice's railway station - it had already been sold to the Baron Henry of Rothschild who had also raced cars in Nice.

In 1901, the car amazed the automobile world. Jellinek again won the Nice races, easily beating his opponents in all the capacity classes and reaching 60 km/h (37 mph). The director of the French Automobile Club, Paul Meyan, stated: "We have entered the Mercedes era", a sentiment echoed by newspapers worldwide.

The records set by the new Mercedes amazed the entire automobile

world. DMG's sales shot up, filling its Stuttgart plant to full capacity

and consolidating its future as a car making company. The number of

employees steadily increased from 340 in 1900 to 2,200 in 1904. In 1902, on June 23, the company decided to use the Mercedes name as the trademark for its entire automobile production and officially registered it on September 26.

As well as shaving off his side whiskers, the overjoyed Emil Jellinek, in Vienna in June 1903 at the age of 50, changed his name to Jellinek - Mercedes, commenting: "This is probably the first time that a father has taken his daughter's name". From then on, he signed himself E.J. Mercédès.

Jellinek and his enthusiastic associates were distributing DMG - Mercedes models worldwide, six hundred were sold by 1909, making millions for DMG. He supplied cars to all 150 members of Nice's Automobile Club and also supported racing teams all over Europe. His life was absorbed by the business, spending much time away from home, and sending many telegrams.

As the 1900s continued, his passion for the Mercedes began to fade. He tired of the special requests being made by his highly demanding aristocratic customers. He also became disillusioned by DMG's technical department which he called "those donkeys" and built his own large repair facilities at Nice behind Villa Mercedes. Wilhelm Maybach, his favorite designer, left DMG in 1907. He also so angered DMG's chairman that in 1908 he permanently cancelled Jellinek's original contract.

His diplomatic career continued and he was Austro - Hungarian Consulate General

in successively Nice (1907), Mexico and Monaco. In 1909 when in Monte

Carlo, Jellinek finally severed his commercial activities to concentrate

on his consular work but did purchase some casinos in the region.

Just before war broke out in 1914 the Austrian government charged Jellinek for taxes on his French properties. The family then moved to Semmering, Austria. While being treated at a sanatorium in Kissingen by Dr. Von Dapper, he ceded the Baden mansion to his family, writing: "(The Baden Villa) disturbs me terribly, I cannot sleep and that is detrimental to my health!.".

When Austro - Hungary entered in war on July 28, 1914, Jellinek and his family stopped speaking French outside their property. Later that year, they moved to Meran (France) but there, he was accused of espionage for Germany, supposedly hiding saboteurs in his Mediterranean yachts. At the same time, the Austrians suspected his wife Anaise.

Fleeing in 1917, they finished up in Geneva, in neutral Switzerland, where Emil Jellinek was temporarily arrested again. He stayed there until his death on January 21, 1918, at the age of 64 . All his French properties were later forfeited. In 1982, his remains have rested near Rachel's tomb, in Nice's Catholic Cemetery.

A decade after his death in 1926, amid the German post war crisis, DMG merged with Benz to become the Daimler - Benz company with their automobiles called Mercedes - Benz. Daimler - Benz purchased Chrysler

in 1998 and became DaimlerChrysler until August 2007, when Chrysler was

sold off to Cerberus Capital Management. The company is now known as

Daimler AG.

In the Mercedes ' global boom in 1900, Jellinek purchased several properties including:

- Mercedes exhibition room in the Champs - Élysées, Paris.

- Grand hotels: Royal and Scribe in Nice and the Astoria, in Paris.

His most important properties were:

- The Villa Mercedes in Nice. No. 57, Promenade des Anglais.

- The Villa Mercedes II in Nice. No. 54, Promenade des Anglais. Bought in 1902.

- Villa Jellinek - Mercedes, Wienerstrasse 39 - 45, in Baden (next to the original vineyard house). Purchasing it as a building plot in 1891, Jellinek built a large mansion, adding to it progressively from 1909 until it had 50 rooms, 8 bathrooms and 23 toilets. In 1945 the Russian Army destroyed all but the garage and two rooms. Afterwards, the land was divided and sold and is now occupied by a gas station and a smaller building built in 1900.

- Chauteau Robert. An immense house located between Toulon and Nice. Officially it was Jellinek's private residence, though he spent most of the time in the Villa Mercedes of Nice.

Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovsky (17 September [O.S. 5 September] 1857 – 19 September 1935) was an Imperial Russian and Soviet rocket scientist and pioneer of the astronautic theory. Along with his followers the German Hermann Oberth and the American Robert H. Goddard, he is considered to be one of the founding fathers of rocketry and astronautics. His works later inspired leading Soviet rocket engineers such as Sergey Korolyov and Valentin Glushko and contributed to the success of the Soviet space program.

Tsiolkovsky spent most of his life in a log house

on the outskirts of Kaluga, about 200 km (120 mi) southwest

of Moscow. A recluse by nature, he appeared strange and bizarre to his

fellow townsfolk.

He was born in Izhevskoye (now in Spassky District, Ryazan Oblast), in the Russian Empire, to a middle class family. His father, Edward Tsiolkovsky (in Polish: Ciołkowski), was Polish; his mother, Maria Yumasheva, was an educated Russian woman. His father was an orthodox priest of Polish descent deported to Russia as a result of his political activities. At the age of 9, Konstantin caught scarlet fever and became hard of hearing. He was not admitted to elementary schools because of his hearing problem, so he was self taught.

After falling behind in his studies, Tsiolkovsky spent three years attending a library where Russian cosmism proponent Nikolai Fyodorov worked. He later came to believe that colonizing space would lead to the perfection of the human race, with immortality and a carefree existence.

Additionally, inspired by the fiction of Jules Verne, Tsiolkovsky theorized many aspects of space travel and rocket propulsion. He is considered the father of spaceflight and the first person to conceive the space elevator, becoming inspired in 1895 by the newly constructed Eiffel Tower in Paris.

Tsiolkovsky worked as a high school mathematics teacher until

retiring in 1920. He did not particularly flourish under a communist system, in particular Tsiolkovsky's support of eugenics

made him politically unpopular. However, from the mid 1920s onwards the

importance of his other work was acknowledged, and he was honored for

it. He died on 19 September 1935 in Kaluga and was buried in state.

Tsiolkovsky stated that he developed the theory of rocketry only as a supplement to philosophical research on the subject. He wrote more than 400 works, most of which are little known to the general reader because of their questionable value.

During his lifetime he published approximately 90 works on space travel and related subjects. Among his works are designs for rockets with steering thrusters, multi - stage boosters, space stations, airlocks for exiting a spaceship into the vacuum of space, and closed cycle biological systems to provide food and oxygen for space colonies.

The first scientific study of Tsiolkovsky dates to the year 1880 - 1881. Unaware of the discoveries already made, he wrote a paper called "Theory of Gases," in which he outlined the basis of the kinetic theory of gases. His second work - "The mechanics of the animal organism" - received favorable feedback and Tsiolkovsky was inducted into the Russian Physico - Chemical Society. The main works of Tsiolkovsky after 1884 dealt with four major areas: the scientific rationale for the all metal balloon (Airship), the streamlined airplane, trains, hovercraft and rockets for interplanetary travel.

Tsiolkovsky developed the first aerodynamic laboratory in Russia in his apartment. In 1897, he built the first Russian wind tunnel with an open test section, developed a method of experiment in it and in 1900, with a grant from the Academy of Sciences, made a purge of the simplest models and determined the drag coefficient of the ball, flat plates, cylinders, cones and other bodies. Tsiolkovsky's work in the field of aerodynamics was a source of ideas for Zhukovsky. Tsiolkovsky described the airflow of bodies of different geometric shapes.

Tsiolkovsky studied the mechanics of powered flight, which were designated "dirigibles" (the word "airship" had not yet been invented). Tsiolkovsky first proposed the idea of an all metal dirigible, and built its model. The first printed work on the airship was "Managed Metallic Balloon" (1892), in which was given the scientific and technical rationale for the design of an airship with a metal sheath. Progressive for his time, Tsiolkovsky was not supported on the airship project: the author was refused a grant to build the model. An appeal to the General Aviation Staff of the Russian army also had no success. In 1892, he turned to the new and unexplored field of aircraft heavier than air. Tsiolkovsky's idea was to build an airplane with a metal frame. In the article "An airplane or a birdlike (aircraft) flying machine" (1894) are the descriptions and drawings of a monoplane, which by its appearance and aerodynamics was the design of an anticipated construction aircraft that would emerge over the next 15 – 18 years. In an Aviation Airplane, the wings have a thick profile with a rounded front edge and the fuselage is faired. But work on the airplane, as well as on the airship, did not receive recognition from the official representatives of Russian science. For further research Tsiolkovsky had neither the means nor even moral support.

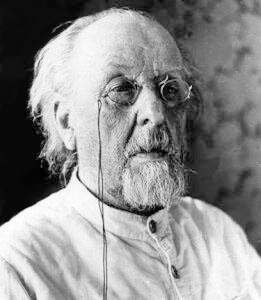

Since 1896 Tsiolkovsky systematically studied the theory of motion of jet apparatus. Thoughts on the use of the rocket principle in the cosmos were expressed as early as 1883 by Tsiolkovsky. But a rigorous theory of jet propulsion described them in 1896. Tsiolkovsky derived the formula (it was called "Formula of Aviation"), establishing the relationship between:

- speed of a rocket at any moment

- specific impulse fuel

- mass of the rocket in the initial and final time

When finished recording the math, Tsiolkovsky automatically set the date: May 10, 1897. In the same year the formula for the motion of the body of variable mass was published in the thesis of the Russian mathematician I.V. Meshchersky ("Dynamics of a point of variable mass," IV Meshchersky, St. Petersburg., 1897).

His most important work, published in 1903, was The Exploration of Cosmic Space by Means of Reaction Devices (Russian: Исследование мировых пространств реактивными приборами). Tsiolkovsky calculated, with the Tsiolkovsky equation, that the horizontal speed required for a minimal orbit around the Earth is 8,000 m/s (5 miles per second) and that this could be achieved by means of a multistage rocket fueled by liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen.

In 1903 he published an article "Investigation of outer space rocket appliances", in which for the first time it was proved that a rocket could perform space flight. In this article, and its subsequent sequels (1911 and 1914), he developed some ideas of missiles and the use of liquid rocket engine.

Result of the first publication was not the one expected by Tsiolkovsky. No foreign scientists appreciated the research, which today is a major science. He was simply ahead of his time. In 1911 he published the second part of the work "The study of outer space rocket appliances." Tsiolkovsky evaluates work to overcome the force of gravity, determines the speed needed to exit the device into the solar system ("escape velocity") and flight time. This time, Tsiolkovsky's article made a splash in the scientific world. Tsiolkovsky found many friends in the world of science.

In 1926 - 1929 Tsiolkovsky solved the practical problem of how to get fuel into the rocket to get the separation speed and leave the Earth. It turned out that the finite speed of the rocket depends on the rate of gas flowing from it and from how many times the weight of the fuel exceeds the empty weight of the rocket.

Tsiolkovsky conceived a number of ideas that have been used in rockets. They included: gas rudders (graphite) for the rocket flight control and change the trajectory of its center of mass, use of components of the fuel to cool the outer shell of the spacecraft (during re-entry to Earth), the walls of the combustion chamber and nozzle, pump system feeding the fuel components, the optimal descent trajectory of the spacecraft while returning from space, etc. In the field of rocket propellants Tsiolkovsky studied a large number of different oxidizing and combustible fuel and recommended pairings: liquid oxygen and hydrogen and oxygen with hydrocarbons. Tsiolkovsky did much fruitful work on the creation of the theory of jet aircraft, and invented his chart Gas Turbine Engine In 1927 he published the theory and design of a train on an air cushion. He first proposed a "bottom of the retractable body" chassis. Space flight and the airship were the main problems to which he devoted his life. Tsiolkovsky had been developing the idea of the air cushion since 1921, publishing a fundamental paper on it in 1927, entitled "Air Resistance and the Express Train" (Russian: Сопротивление воздуха и скорый поезд). In 1929 Tsiolkovsky proposed the construction of multistage rockets in his book Space Rocket Trains (Russian: Космические ракетные поезда).

Tsiolkovsky championed the idea of the diversity of life in the universe, and was the first theorist and advocate of human space exploration.

Hearing problems did not prevent the scientist from having a good understanding of music. There is his work "The Origin of music and its essence."

Tsiolkovsky never built a rocket; he apparently did not expect many of his theories to ever be implemented. Only late in his lifetime was Tsiolkovsky honored for his pioneering work. He supported the Bolshevik Revolution, and the new Soviet government wished to identify itself with technology. In 1918 he was elected as a member of the Socialist Academy, and in 1921 received a lifetime pension.

Although many called his ideas impractical, Tsiolkovsky influenced later rocket scientists throughout Europe, like Wernher von Braun. Russian search teams at Peenemünde found a German translation of a book by Tsiolkovsky of which "almost every page... was embellished by von Braun's comments and notes." Leading Russian rocket engine designer Valentin Glushko and rocket designer Sergey Korolyov studied Tsiolkovsky's works as youths, and both sought to turn Tsiolkovsky's theories into reality. In particular, Korolyov saw traveling to Mars as the more important priority, until in 1964 he decided to compete with the American Project Apollo for the moon.

Tsiolovsky wrote a book called The Will of the Universe. The Unknown Intelligence in 1928 in which he propounded a philosophy of panpsychism. He believed humans would eventually colonize the Milky Way galaxy.

- The State Museum of the History of Cosmonautics in Kaluga now bears his name.

- The crater Tsiolkovskiy (the most prominent crater on the far side of the Moon) was named after him, while asteroid 1590 Tsiolkovskaja was named after his wife. (The Soviet Union obtained naming rights by operating Luna 3, the first space device to successfully transmit images of the side of the moon not seen from Earth.)

- There is a statue of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky directly outside the Sir Thomas Brisbane Planetarium in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia.