<Back to Index>

- Tectonic Plate Philippine Sea Plate

- Tectonic Plate Scotia Plate

PAGE SPONSOR

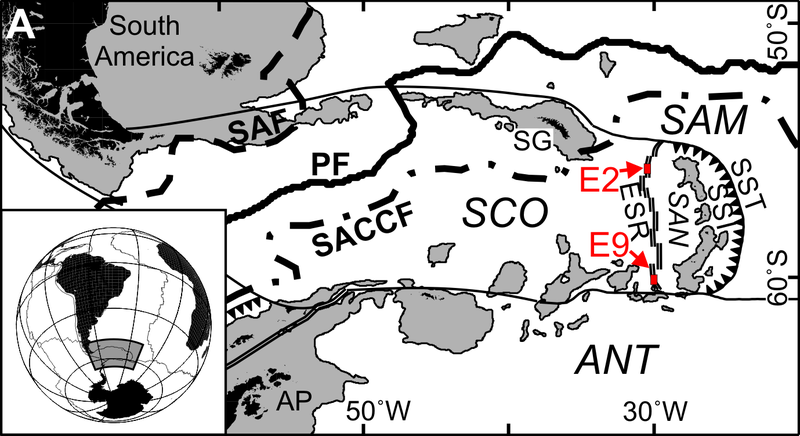

The Philippine Sea Plate is a tectonic plate comprising oceanic lithosphere that lies beneath the Philippine Sea, to the east of the Philippines. Most segments of the Philippines, including northern Luzon, are part of the Philippine Mobile Belt, which is geologically and tectonically separate from the Philippine Sea Plate.

To the north, the Philippine Sea Plate meets the Okhotsk Plate at the Nankai Trough. The Philippine Sea Plate, the Amurian Plate, and the Okhotsk Plate meet at Mount Fuji in Japan. Thickened crust of the Izu - Bonin - Mariana arc colliding with Japan constitutes the Izu Collision Zone.

The eastern side of the Philippine Sea Plate is a convergent boundary with the Pacific Plate subducting at the Izu - Ogasawara Trench. The east of the plate includes the Izu - Ogasawara (Bonin) and the Mariana Islands, forming the Izu - Bonin - Mariana Arc system. There is also a divergent boundary between the Philippine Sea Plate and the small Mariana Plate which carries the Mariana Islands.

To the south, the Philippine Sea Plate is bounded by the Caroline Plate and Bird's Head Plate.

To the west, the Philippine Sea Plate subducts under the Philippine Mobile Belt at the Philippine Trench and the East Luzon Trench.

To the northwest the Philippine Sea Plate meets Taiwan and the Nansei islands on the Okinawa Plate, and southern Japan on the Amurian Plate.

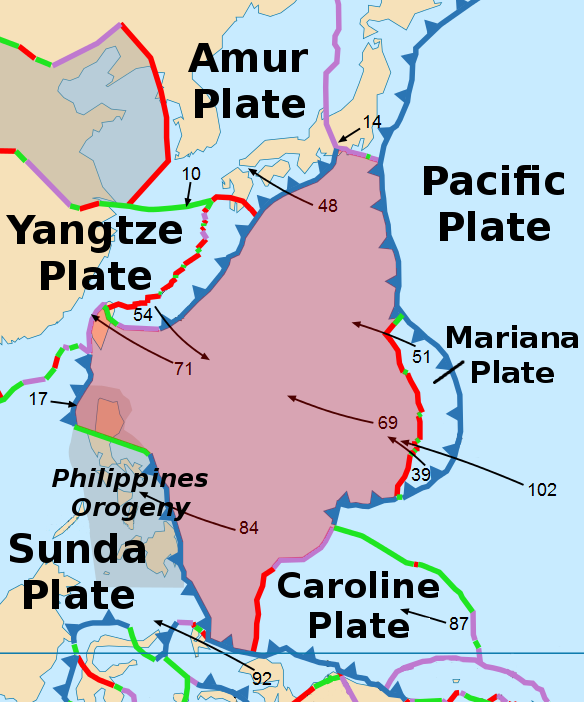

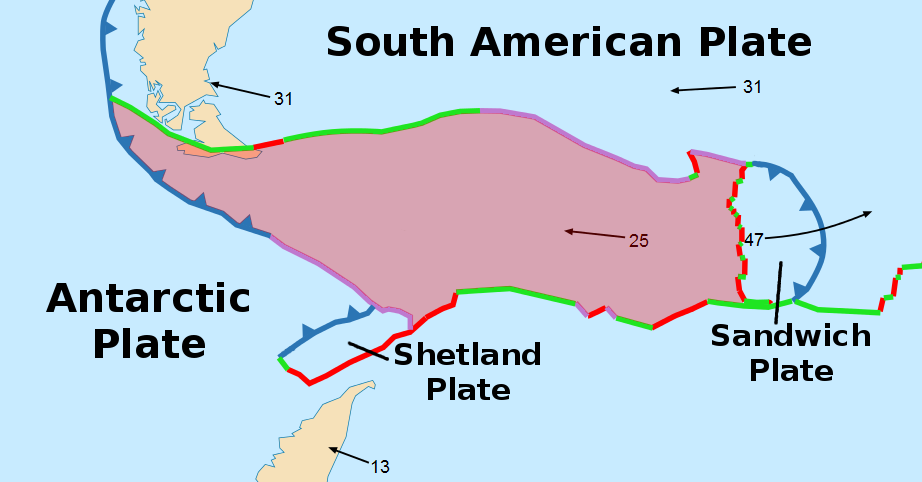

The Scotia Plate, named after the sea which overlies it, is a tectonic plate on the edge of the South Atlantic and Antarctic Ocean. Thought to have formed during the early Eocene with the opening of the Drake Passage, it is a minor plate whose movement is largely controlled by the two major plates that surround it; the South American plate and Antarctic plate. Having formed as oceanic crust, it is almost completely submerged with only the small exception of the South Georgia Islands on its north - eastern edge and the southern tip of South America.

Bounded by subducting, spreading and transform ridges, the Scotia plate lies in a particular setting. Surrounded by 2 major and 3 minor plates, its tectonic location is generally reflective of the relative motion between the Antarctic plate and the South American plate.

The Southern edge of the plate is bordered by the Antarctic plate forming the South Scotia Ridge. The South Scotia ridge is a left lateral transform boundary sliding at a rate of roughly 11 mm/yr. Though the South Scotia ridge is overall a transform fault, small sections of the ridge are spreading to make up for the somewhat jagged shape of the boundary.

The Western edge of the plate is bounded by the Antarctic plate, forming the Shackleton Fracture zone and the Southern Chile trench. The Southern Chile trench is a southern extension of the subduction of the Antarctic and Nazca plate below South America. Heading south along the ridge, the subduction rate decreases until its remaining oblique motion evolves into the Shackleton Fracture Zone transform boundary. The Shackleton Fracture zone is a left lateral transform boundary that occupies the southern half of the Antarctic - Scotia plate boundary. The relative motion between the Scotia plate and the Antarctic plate on the western boundary is roughly 13 mm/yr.

The Northern edge of the Scotia plate is bounded by the South American plate forming the North Scotia ridge. The North Scotia ridge is a left lateral transform boundary with a transform rate of roughly 7.1 mm/yr.

The eastern edge of the Scotia plate is a spreading ridge bounded by the South Sandwich microplate forming the East Scotia ridge. The East Scotia ridge is a back - arc spreading ridge that formed due to subduction of the South American plate below the South Sandwich plate along the South Sandwich Island arc. Exact spreading rates in the literature are still being disputed, but it has been agreed rates are between 65 - 90 mm/yr.

The south-western edge of the plate is bounded by the Shetland microplate separating the Shackleton Fracture Zone and the South Scotia ridge.

Highly disputed, tectonisists have been unable to determine whether the

South Georgian Islands are part of the Scotia plate or have been

recently amalgamated to the South American plate. Surface expressions of

the plate boundary are found north of the islands suggesting a

long term presence of the transform fault there. Yet seismic studies

have identified strain and thrusting south of the islands indicating

the possible shift of the transform fault to an area south of the

island. It has also been suggested that the plate may have broken off

from the Scotia plate forming a new independent South Georgia microplate;

yet there is little evidence to make this conclusion.

The timing of the formation of the Scotia plate and opening of the Drake Passage has long been the subject of much debate due to its important implications for changes in ocean currents and shifts in paleo - climate. The thermal isolation of Antarctica and formation of the Antarctic ice sheet has largely been attributed to the opening of the Drake Passage.

During the early Eocene (50 Ma), the Drake passage between the

southern tip of South America at Cape Horn, Chile, and the South Shetland

Islands of Antarctica was a small opening with limited circulation. A

change in motion between the South American plate and the Antarctic

plate would have severe effects, causing seafloor spreading and the

formation of the Scotia plate.

Marine geophysical data indicates that motion between the South

American plate and the Antarctic plate shifted from N-S to WNW-ESE

accompanied by an eightfold increase in the separation rate.

This shift in spreading initiated crustal thinning and by 30-34 Ma, the

Mid - Scotia spreading ridge formed. Spreading began to generate two new

oceanic plates between South American and Antarctica, the so called

Magellan and Central Scotia plates. Thinner and denser than the

continental Antarctic and South American plates, the growing Magellan

and Central Scotia plates formed a deep and increasingly wide passage,

the Drake Passage between South America and Antarctica. The eventual

death of the Mid - Scotia ridge led the Magellan and Central Scotia plates

to join forming the Scotia plate as seen today.