<Back to Index>

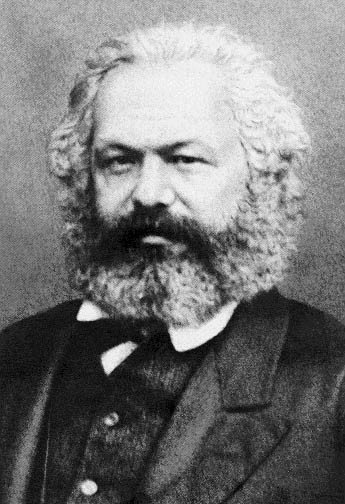

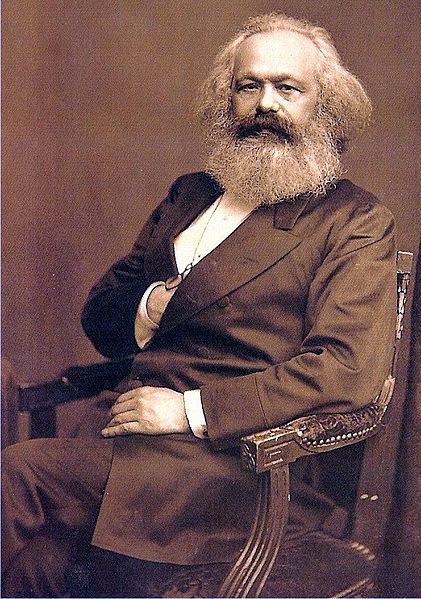

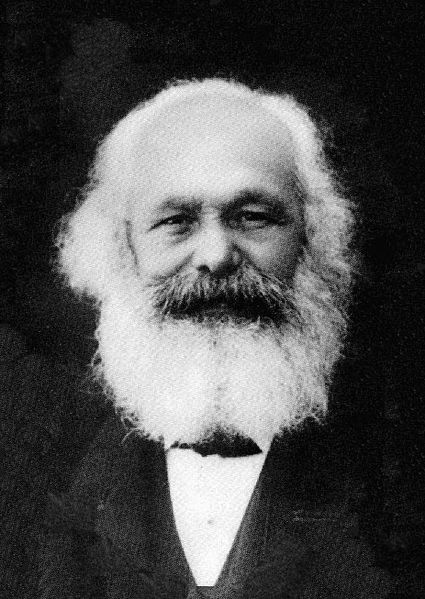

- Philosopher, Economist and Sociologist Karl Heinrich Marx, 1818

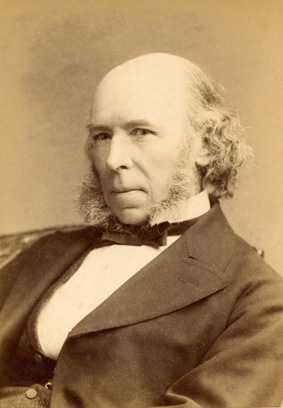

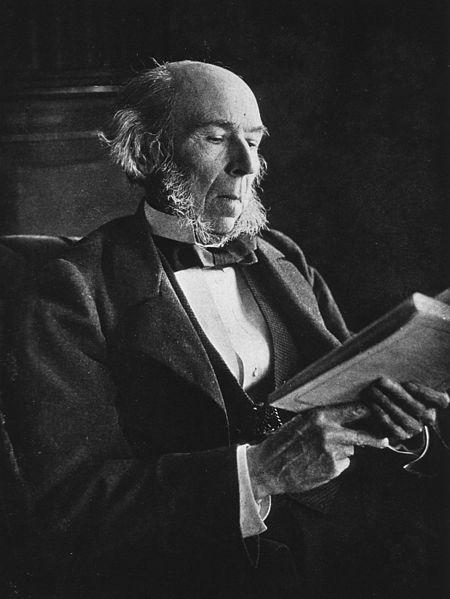

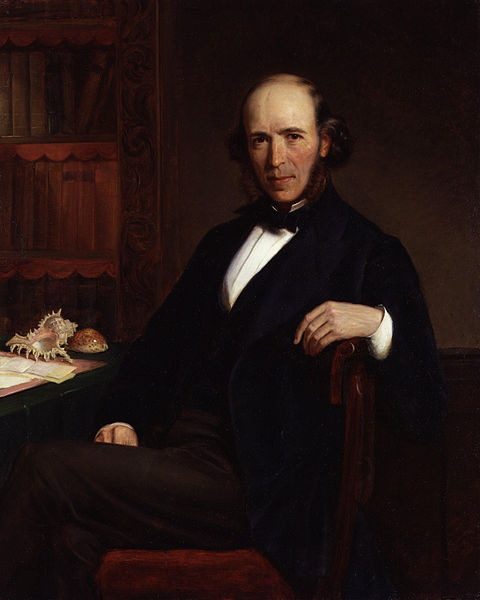

- Philosopher, Biologist and Sociologist Herbert Spencer, 1820

PAGE SPONSOR

Karl Heinrich Marx (5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, historian, journalist and revolutionary socialist. His ideas played a significant role in the development of social science and the socialist political movement. He published various books during his lifetime, with the most notable being The Communist Manifesto (1848) and Capital (1867 – 1894); some of his works were co-written with his friend and fellow German revolutionary socialist, Friedrich Engels.

Born into a wealthy middle class family in Trier, formerly in Prussian Rhineland now called Rhineland - Palatinate, Marx studied at both the University of Bonn and the University of Berlin, where he became interested in the philosophical ideas of the Young Hegelians. In 1836, he became engaged to Jenny von Westphalen, marrying her in 1843. After his studies, he wrote for a radical newspaper in Cologne, and began to work out his theory of dialectical materialism. Moving to Paris in 1843, he began writing for other radical newspapers. He met Engels in Paris, and the two men worked together on a series of books. Exiled to Brussels, he became a leading figure of the Communist League, before moving back to Cologne, where he founded his own newspaper. In 1849 he was exiled again and moved to London together with his wife and children. In London, where the family was reduced to poverty, Marx continued writing and formulating his theories about the nature of society and how he believed it could be improved, and also campaigned for socialism — he became a significant figure in the International Workingmen's Association.

Marx's theories about society, economics and politics — collectively known as Marxism — hold that all societies progress through the dialectic of class struggle: a conflict between an ownership class which controls production and a lower class which produces the labor for such goods. Heavily critical of the current socio - economic form of society, capitalism, he called it the "dictatorship of the bourgeoisie", believing it to be run by the wealthy classes purely for their own benefit, and predicted that, like previous socioeconomic systems, it would inevitably produce internal tensions which would lead to its self destruction and replacement by a new system, socialism. He argued that under socialism society would be governed by the working class in what he called the "dictatorship of the proletariat", the "workers state" or "workers' democracy". He believed that socialism would, in its turn, eventually be replaced by a stateless, classless society called communism. Along with believing in the inevitability of socialism and communism, Marx actively fought for the former's implementation, arguing that both social theorists and underprivileged people should carry out organized revolutionary action to topple capitalism and bring about socio - economic change.

Revolutionary socialist governments espousing Marxist concepts took

power in a variety of countries in the 20th century, leading to the

formation of such socialist states as the Soviet Union in 1922 and the People's Republic of China

in 1949. Many labor unions and worker's parties worldwide were also

influenced by Marxist ideas. Various theoretical variants, such as

Leninism, Stalinism, Trotskyism and Maoism, were developed. Marx is

typically cited, with Émile Durkheim and Max Weber, as one of the three

principal architects of modern social science. Marx has been described as one of the most influential figures in human history.

Karl Heinrich Marx was born on 5 May 1818 at 664 Brückergasse in Trier, a town located in the Kingdom of Prussia's Province of the Lower Rhine. His ancestry was Jewish, with his paternal line having supplied the rabbis of Trier since 1723, a role that had been taken up by his own grandfather, Meier Halevi Marx; Meier's son and Karl's father would be the first in the line to receive a secular education. His maternal grandfather was a Dutch rabbi. Karl's father, Herschel Marx, was middle class and relatively wealthy: the family owned a number of Moselle vineyards; he converted from Judaism to the Protestant Christian denomination of Lutheranism prior to his son's birth, taking on the German forename of Heinrich over Herschel. In 1815, he began working as an attorney and in 1819 moved his family from a five room rented apartment into a ten room property near the Porta Nigra. A man of the Enlightenment, Heinrich Marx was interested in the ideas of the philosophers Immanuel Kant and Voltaire, and took part in agitation for a constitution and reforms in Prussia, which was then governed by an absolute monarchy. Karl's mother, born Henrietta Pressburg, was a Dutch Jew who, unlike her husband, was only semi literate. She claimed to suffer from "excessive mother love", devoting much time to her family, and insisting on cleanliness within her home. She was from a prosperous business family. Her family later founded the company Philips Electronics: she was great - aunt to Anton and Gerard Philips, and great - great - aunt to Frits Philips. Her brother, Marx's uncle Benjamin Philips (1830 - 1900), was a wealthy banker and industrialist, who Karl and Jenny Marx would later often come to rely upon for loans, while they were exiled in London.

Heinrich Marx converted to Lutheran Protestantism in 1816 or 1817 in order to continue practicing law after the Prussian edict denying Jews to the bar. Karl was born in 1818 and baptized in 1824, but his mother, Henriette, did not convert until 1825, when Karl was 7. There is no evidence that the Marx family actually embraced Lutheranism, although there is no evidence they were practicing Jews. Marx identified himself as an atheist.

Little is known about Karl Marx's childhood. He was privately

educated until 1830, when he entered Trier High School, whose headmaster

Hugo Wyttenbach was a friend of his father. Wyttenbach had employed many liberal humanists

as teachers; this angered the government so that the police raided the

school in 1832, discovering what they labeled seditious literature

espousing political liberalism being distributed amongst the students.

In 1835, Karl, then aged seventeen, began attending the University of

Bonn, where he wished to study philosophy and literature, but his father

insisted on law as a more practical field of study.

He was able to avoid military service when he turned eighteen because

he suffered from a weak chest. Being fond of alcoholic beverages, at

Bonn he joined the Trier Tavern Club drinking society (Landsmannschaft der Treveraner) and at one point served as its co-president.

Marx was more interested in drinking and socializing than studying law,

and because of his poor grades, his father forced him to transfer to

the far more serious and academically oriented University of Berlin, where his legal studies became less significant than excursions into philosophy and history.

In 1836, Marx became engaged to Jenny von Westphalen, a beautiful baroness of the Prussian ruling class — "the most desirable young woman in Trier" — who broke off her engagement with a young aristocratic second lieutenant to be with him. Their eventual marriage was controversial for breaking three social taboos of the period; it was a marriage between a daughter of a noble background and a man of Jewish origin as well as being between individuals who belonged to the middle and upper class (aristocracy), respectively, and between a man and an older woman. Such issues were lessened by Marx's friendship with Jenny's father, Baron Ludwig von Westphalen, a liberal thinking aristocrat. Marx dedicated his doctoral thesis to him. The couple married seven years later, on 19 June 1843, at the Pauluskirche in Bad Kreuznach.

Marx became interested in, but critical of, the work of the German philosopher G. W. F Hegel

(1770 – 1831), whose ideas were widely debated amongst European

philosophical circles at the time. Marx wrote about falling ill "from

intense vexation at having to make an idol of a view I detested." He

became involved with a group of radical thinkers known as the Young

Hegelians, who gathered around Ludwig Feuerbach and Bruno Bauer. Like Marx, the Young Hegelians were critical of Hegel's metaphysical assumptions, but still adopted his dialectical method

in order to criticize established society, politics and religion. Marx

befriended Bauer, and in July 1841 the two scandalized their class in

Bonn by getting drunk, laughing in church, and galloping through the

streets on donkeys. During that period, Marx concentrated on his

criticism of Hegel and certain other Young Hegelians.

Marx also wrote for his own enjoyment, writing both non-fiction and fiction. In 1837, he completed a short novel, Scorpion and Felix; a drama, Oulanem and some poems, none of which were published. In 1971, Marx's one act play Oulanem was made available in English by author Robert Payne. According to Payne, the title Oulanem is an anagram for "Manuelo" which is a variant of "Emmanuel" meaning "God is with us". He soon gave up writing fiction for other pursuits, including learning English and Italian.

He was deeply engaged in writing his doctoral thesis, The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature, which he finished in 1841. The essay has been described as "a daring and original piece of work in which he set out to show that theology must yield to the superior wisdom of philosophy", and as such was controversial, particularly among the conservative professors at the University of Berlin. Marx decided to submit it instead to the more liberal University of Jena, whose faculty awarded him his PhD based on it.

From considering an academic career, Marx turned to journalism. He moved to the city of Cologne in 1842, where he began writing for the radical newspaper Rheinische Zeitung, where he expressed his increasingly socialist views on politics. He criticized the governments of Europe and their policies, but also liberals and other members of the socialist movement whose ideas he thought were ineffective or outright anti - socialist. The paper eventually attracted the attention of the Prussian government censors, who checked every issue for potentially seditious material before it could be printed. Marx said, "Our newspaper has to be presented to the police to be sniffed at, and if the police nose smells anything un-Christian or un-Prussian, the newspaper is not allowed to appear." After the paper published an article strongly criticizing the monarchy in Russia, the Russian Tsar Nicholas I, an ally of the Prussian monarchy, requested that the Rheinische Zeitung be banned. The Prussian government shut down the paper in 1843. Marx wrote for the Young Hegelian journal, the Deutsche Jahrbücher, in which he criticized the censorship instructions issued by Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. His article was censored and the newspaper closed down by the authorities shortly after.

In 1843, Marx published On the Jewish Question, in which he

distinguished between political and human emancipation. He also examined

the role of religious practice in society. That same year he published Contribution to Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right, in which he dealt more substantively with religion, describing it as "the opiate of the people". He completed both works shortly before leaving Cologne.

Following the government imposed shutdown of the Rheinische Zeitung, Marx got involved with a new radical newspaper, the Deutsch - Französische Jahrbücher (German - French Annals), which was then being set up by Arnold Ruge, another German socialist revolutionary. The paper was based not in Germany, but in the city of Paris in neighboring France, and it was here that both Marx and his wife moved in October 1843. They initially lived with Ruge and his wife communally at 23 Rue Vaneau, but finding these living conditions difficult, the Marxes moved out following the birth of their daughter Jenny in 1844. Although it was intended to attract writers from both France and the German states, the Deutsch - Französische Jahrbücher was dominated by the latter, with the only non-German writer being the exiled Russian anarcho - communist Michael Bakunin. Only one issue was ever published, but it was relatively successful, largely owing to the inclusion of Heinrich Heine's satirical odes on King Ludwig of Bavaria, which led to those copies sent to Germany being confiscated by the state's police force.

It was in Paris that, on 28 August 1844, Marx met German socialist Friedrich Engels at the Café de la Régence after becoming interested in the ideas that the latter had expressed in articles written for the Rheinische Zeitung and the Deutsch - Französische Jahrbücher. Although they had briefly met each other at the offices of the Rheinische Zeitung in 1842, it was here in Paris that they began their friendship that would last for the rest of their lives. Engels showed Marx his recently published book, The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844, which convinced Marx that the working class would be the agent and instrument of the final revolution in history. Engels and Marx soon set about writing a criticism of the philosophical ideas of Marx's former friend, the Young Hegelian Bruno Bauer, which would be published in 1845 as The Holy Family. Although critical of Bauer, Marx was increasingly influenced by the ideas of the other Young Hegelians Max Stirner and Ludwig Feuerbach, but eventually also abandoned Feuerbachian materialism as well.

In 1844 Marx wrote The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts, a work which covered numerous topics, and went into detail to explain Marx's concept of alienated labor. A year later Marx would write Theses on Feuerbach, best known for the statement that "the philosophers have only interpreted the world, the point is to change it". This work contains Marx's criticism of materialism (for being contemplative), idealism (for reducing practice to theory) and overall, criticizing philosophy for putting abstract reality above the physical world. It thus introduced the first glimpse at Marx's historical materialism, an argument that the world is changed not by ideas but by actual, physical, material activity and practice.

After the collapse of the Deutsch - Französische Jahrbücher,

Marx, still living on the Rue Vaneau, began writing for what was then

the only uncensored German language radical newspaper in Europe, Vorwärts!.

Based in Paris, the paper had been established and was run by many

activists connected to the revolutionary socialist League of the Just,

which would come to be better known as the Communist League within a few

years. In Vorwärts!,

Marx continued to refine his views on socialism based upon the Hegelian

and Feuerbachian ideas of dialectical materialism, whilst at the same

time criticizing various liberals and other socialists operating in

Europe at the time. However in 1845, after receiving a request from the

Prussian king, the French government agreed to shut down Vorwärts!, and furthermore, Marx himself was expelled from France by the interior minister François Guizot.

Unable either to stay in France or to move to Germany, Marx decided to emigrate to Brussels in Belgium, but had to pledge not to publish anything on the subject of contemporary politics in order to enter. In Brussels, he associated with other exiled socialists from across Europe, including Moses Hess, Karl Heinzen and Joseph Weydemeyer, and soon Engels moved to the city in order to join them. In 1845 Marx and Engels visited the leaders of the Chartists, a socialist movement in Britain, using the trip as an opportunity to study in various libraries in London and Manchester. In collaboration with Engels he also set about writing a book which is often seen as his best treatment of the concept of historical materialism, The German Ideology; the work, like many others, would not see publication in Marx's lifetime, being published only in 1932. He followed this with The Poverty of Philosophy (1847), a response to the French anarcho - socialist Pierre - Joseph Proudhon's The Philosophy of Poverty and a critique of French socialist thought in general.

These books laid the foundation for Marx and Engels's most famous work, a political pamphlet that has since come to be commonly known as The Communist Manifesto. First published on 21 February 1848, it laid out the beliefs of the Communist League, a group who had come increasingly under the influence of Marx and Engels, who argued that the League must make their aims and intentions clear to the general public rather than hiding them as they had formerly been doing. The opening lines of the pamphlet set forth the principal basis of Marxism, that "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles." It goes on to look at the antagonisms that Marx claimed were arising between the clashes of interest between the bourgeoisie (the wealthy middle class) and the proletariat (the industrial working class). Proceeding on from this, the Manifesto presents the argument for why the Communist League, as opposed to other socialist and liberal political parties and groups at the time, was truly acting in the interests of the proletariat to overthrow capitalist society and replace it with socialism.

Later that year, Europe experienced a series of protests, rebellions,

and often violent upheavals, the Revolutions of 1848. In France, a

revolution led to the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of

the French Second Republic. Marx was supportive of such activity, and having recently received a substantial inheritance from his father of either 6000 or 5000 francs, allegedly used a third of it to arm Belgian workers who were planning revolutionary action. Although the veracity of these allegations is disputed,

the Belgian Ministry of Justice accused him of it, subsequently

arresting him, and he was forced to flee back to France, where, with a

new republican government in power, he believed that he would be safe.

Temporarily settling down in Paris, Marx transferred the Communist League executive headquarters to the city and also set up a German Workers' Club with various German socialists living there. Hoping to see the revolution spread to Germany, in 1848 Marx moved back to Cologne (Köln) where he began issuing a handbill entitled the Demands of the Communist Party in Germany, in which he argued for only four of the ten points of the Communist Manifesto, believing that in Germany at that time, the bourgeoisie must overthrow the feudal monarchy and aristocracy before the proletariat could overthrow the bourgeoisie. On 1 June, Marx started publication of the daily Neue Rheinische Zeitung ("New Rhenish Newspaper"), which he helped to finance through his recent inheritance from his father. Designed to put forward news from across Europe with his own Marxist interpretation of events, Marx remained one of its primary writers, accompanied by other fellow members of the Communist League who wrote for the paper, although despite their input it remained, according to Friedrich Engels, "a simple dictatorship by Marx", who dominated the choice of content.

Whilst editor of the paper, Marx and the other revolutionary

socialists were regularly harassed by the police, and Marx was brought

to trial on several occasions, facing various allegations including

insulting the Chief Public Prosecutor, an alleged press misdemeanor and

inciting armed rebellion through tax boycotting, although each time he was acquitted. Meanwhile, the democratic parliament in Prussia collapsed, and the king, Frederick William IV,

introduced a new cabinet of his reactionary supporters, who implemented

counter - revolutionary measures to expunge leftist and other

revolutionary elements from the country. As a part of this, the Neue Rheinische Zeitung was soon suppressed and Marx was ordered to leave the country on 16 May. Marx returned to Paris, which was then under the grip of both a reactionary counter revolution and a cholera

epidemic, and was soon expelled by the city authorities who considered

him a political threat. With his wife Jenny expecting their fourth

child, and not able to move back to Germany or Belgium, in August 1849

he sought refuge in London.

Marx moved to London in May 1849 and would remain in the city for the rest of his life. It was here that he founded the new headquarters of the Communist League, and got heavily involved with the socialist German Workers' Educational Society, who held their meetings in Great Windmill Street, Soho, central London's entertainment district. Marx devoted himself to two activities: revolutionary organizing, and an attempt to understand political economy and capitalism. For the first few years he and his family lived in extreme poverty. His main source of income was his colleague, Engels, who derived much of his income from his family's business. Marx also briefly worked as correspondent for the New York Tribune in 1851.

From December 1851 to March 1852 Marx wrote The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon, a work on the French Revolution of 1848, in which he expanded upon his concepts of historical materialism, class struggle and the dictatorship of the proletariat, advancing the argument that victorious proletariat has to smash the bourgeois state.

The 1850s and 1860s also mark the line between what some scholars see as idealistic, Hegelian young Marx from the more scientifically minded mature Marx writings of the later period. This distinction is usually associated with the structural Marxism school; not all scholars agree that it indeed exists.

In 1864 Marx became involved in the International Workingmen's Association (also known as First International). He became a leader of its General Council, to whose General Council he was elected at its inception in 1864. In that organization Marx was involved in the struggle against the anarchist wing centered around Mikhail Bakunin (1814 – 1876). Although Marx won this contest, the transfer of the seat of the General Council from London to New York in 1872, which Marx supported, led to the decline of the International. The most important political event during the existence of the International was the Paris Commune of 1871 when the citizens of Paris rebelled against their government and held the city for two months. On the bloody suppression of this rebellion, Marx wrote one of his most famous pamphlets, The Civil War in France, a defense of the Commune.

Given the repeated failures and frustrations of workers' revolutions

and movements, Marx also sought to understand capitalism, and spent a

great deal of time in the reading room of the British Museum studying

and reflecting on the works of political economists and on economic

data.

By 1857 he had accumulated over 800 pages of notes and short essays on

capital, landed property, wage labor, the state, foreign trade and the

world market; this work did not appear in print until 1941, under the

title Grundrisse. In 1859, Marx published Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, his first serious economic work. In the early 1860s he worked on composing three large volumes, the Theories of Surplus Value, which discussed the theoreticians of political economy, particularly Adam Smith and David Ricardo. This work is often seen as the fourth book of Capital, and constitutes one of the first comprehensive treatises on the history of economic thought. In 1867 the first volume of Capital was published, a work which analyzed the capitalist process of production. Here, Marx elaborated his labor theory of value

and his conception of surplus value and exploitation which he argued

would ultimately lead to a falling rate of profit and the collapse of

industrial capitalism.

Volumes II and III remained mere manuscripts upon which Marx

continued

to work for the rest of his life and were published posthumously by

Engels.

During the last decade of his life, Marx's health declined and he became incapable of the sustained effort that had characterized his previous work. He did manage to comment substantially on contemporary politics, particularly in Germany and Russia. His Critique of the Gotha Programme opposed the tendency of his followers Wilhelm Liebknecht and August Bebel to compromise with the state socialism of Ferdinand Lassalle in the interests of a united socialist party. This work is also notable for another famous Marx's quote: "From each according to his ability, to each according to his need."

In a letter to Vera Zasulich

dated 8 March 1881, Marx even contemplated the possibility of Russia's

bypassing the capitalist stage of development and building communism on

the basis of the common ownership of land characteristic of the village mir.

While admitting that Russia's rural "commune is the fulcrum of social

regeneration in Russia", Marx also warned that in order for the mir to

operate as a means for moving straight to the socialist stage without a

preceding capitalist stage, it "would first be necessary to eliminate

the deleterious influences which are assailing it (the rural commune)

from all sides."

Given the elimination of these pernicious influences, Marx allowed,

that "normal conditions of spontaneous development" of the rural commune

could exist.

However, in the same letter to Vera Zasulich, Marx points out that "at

the core of the capitalist system ... lies the complete separation of

the producer from the means of production."

In one of the drafts of this letter, Marx reveals his growing passion

for anthropology, motivated by his belief that future communism would be

a return on a higher level to the communism of our prehistoric past. He

wrote that 'the historical trend of our age is the fatal crisis which

capitalist production has undergone in the European and American

countries where it has reached its highest peak, a crisis that will end

in its destruction, in the return of modern society to a higher form of

the most archaic type — collective production and appropriation'. He

added that 'the vitality of primitive communities was incomparably

greater than that of Semitic, Greek, Roman, etc. societies, and, a

fortiori, that of modern capitalist societies'. Before he died, Marx asked Engels to write up these ideas, which were published in 1884 under the title The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State.

Following the death of his wife Jenny in December 1881, Marx developed a catarrh that kept him in ill health for the last 15 months of his life. It eventually brought on the bronchitis and pleurisy that killed him in London on 14 March 1883. He died a stateless person; family and friends in London buried his body in Highgate Cemetery, London, on 17 March 1883. There were between nine and eleven mourners at his funeral.

Several of his closest friends spoke at his funeral, including Wilhelm Liebknecht and Friedrich Engels. Engels's speech included the passage:

| “ | On the 14th of March, at a quarter to three in the afternoon, the greatest living thinker ceased to think. He had been left alone for scarcely two minutes, and when we came back we found him in his armchair, peacefully gone to sleep — but forever. | ” |

Marx's daughter Eleanor and Charles Longuet and Paul Lafargue, Marx's two French socialist sons - in - law, were also in attendance. Liebknecht, a founder and leader of the German Social - Democratic Party, gave a speech in German, and Longuet, a prominent figure in the French working class movement, made a short statement in French. Two telegrams from workers' parties in France and Spain were also read out. Together with Engels's speech, this constituted the entire program of the funeral. Non - relatives attending the funeral included three communist associates of Marx: Friedrich Lessner, imprisoned for three years after the Cologne communist trial of 1852; G. Lochner, whom Engels described as "an old member of the Communist League" and Carl Schorlemmer, a professor of chemistry in Manchester, a member of the Royal Society, and a communist activist involved in the 1848 Baden revolution. Another attendee of the funeral was Ray Lankester, a British zoologist who would later become a prominent academic.

Upon his own death, Engels left Marx's two surviving daughters a "significant portion" of his $4.8 million estate.

Marx's tombstone bears the carved message: "WORKERS OF ALL LANDS UNITE", the final line of The Communist Manifesto, and from the 11th Thesis on Feuerbach (edited by Engels): "The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways — the point however is to change it". The Communist Party of Great Britain had the monumental tombstone built in 1954 with a portrait bust by Laurence Bradshaw; Marx's original tomb had had only humble adornment. In 1970 there was an unsuccessful attempt to destroy the monument using a homemade bomb.

The later Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm

remarked that "One cannot say Marx died a failure" because, although he

had not achieved a large following of disciples in Britain, his

writings had already begun to make an impact on the leftist movements in

Germany and Russia. Within 25 years of his death, the continental

European socialist parties that acknowledged Marx's influence on their

politics were each gaining between 15 and 47% in those countries with representative democratic elections.

Marx's thought demonstrates influences from many thinkers, including but not limited to:

- Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's philosophy;

- The classical political economy (economics) of Adam Smith and David Ricardo;

- French socialist thought, in particular the thought of Jean - Jacques Rousseau, Henri de Saint - Simon and Charles Fourier;

- Earlier German philosophical materialism, particularly that of Ludwig Feuerbach;

- The working class analysis by Friedrich Engels.

Marx's view of history, which came to be called historical materialism (controversially adapted as the philosophy of dialectical materialism by Engels and Lenin) certainly shows the influence of Hegel's claim that one should view reality (and history) dialectically. However, Hegel had thought in idealist terms, putting ideas in the forefront, whereas Marx sought to rewrite dialectics in materialist terms, arguing for the primacy of matter over idea. Where Hegel saw the "spirit" as driving history, Marx saw this as an unnecessary mystification, obscuring the reality of humanity and its physical actions shaping the world. He wrote that Hegelianism stood the movement of reality on its head, and that one needed to set it upon its feet.

Though inspired by French socialist and sociological thought, Marx criticized utopian socialists, arguing that their favored small scale socialistic communities would be bound to marginalization and poverty, and that only a large scale change in the economic system can bring about real change.

The other important contribution to Marx's revision of Hegelianism came from Engels's book, The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844, which led Marx to conceive of the historical dialectic in terms of class conflict and to see the modern working class as the most progressive force for revolution.

Marx believed that he could study history and society scientifically and discern tendencies of history and the resulting outcome of social conflicts. Some followers of Marx concluded, therefore, that a communist revolution would inevitably occur. However, Marx famously asserted in the eleventh of his Theses on Feuerbach that "philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point however is to change it", and he clearly dedicated himself to trying to alter the world.

Marx polemic with other thinkers often occurred through critique, and thus he has been called "the first great user of critical method in social sciences." He criticised speculative philosophy, equating metaphysics with ideology. By adopting this approach, Marx attempted to separate key findings from ideological biases. This set him apart from many contemporary philosophers.

Fundamentally, Marx assumed that human history involves transforming human nature, which encompasses both human beings and material objects.

Humans recognize that they possess both actual and potential selves.

For both Marx and Hegel, self development begins with an experience of

internal alienation stemming from this recognition, followed by a

realization that the actual self, as a subjective agent, renders its

potential counterpart an object to be apprehended.

Marx further argues that, by molding nature in desired ways, the

subject takes the object as its own, and thus permits the individual to

be actualized as fully human. For Marx, then, human nature — Gattungswesen, or species - being — exists as a function of human labour.

Fundamental to Marx's idea of meaningful labor is the proposition

that, in order for a subject to come to terms with its alienated object,

it must first exert influence upon literal, material objects in the

subject's world. Marx acknowledges that Hegel "grasps the nature of work and comprehends objective man, authentic because actual, as the result of his own work", but characterizes Hegelian self - development as unduly "spiritual" and abstract. Marx thus departs from Hegel by insisting that "the fact that man is a corporeal, actual, sentient, objective being with natural capacities means that he has actual, sensuous objects for his nature as objects of his life expression, or that he can only express his life in actual sensuous objects." Consequently, Marx revises Hegelian "work" into material "labor", and in the context of human capacity to transform nature the term "labor power".

The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.— Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto

Marx had a special concern with how people relate to that most fundamental resource of all, their own labor power. He wrote extensively about this in terms of the problem of alienation. As with the dialectic, Marx began with a Hegelian notion of alienation but developed a more materialist conception. Capitalism mediates social relationships of production (such as among workers or between workers and capitalists) through commodities, including labor, that are bought and sold on the market. For Marx, the possibility that one may give up ownership of one's own labor — one's capacity to transform the world — is tantamount to being alienated from one's own nature; it is a spiritual loss. Marx described this loss as commodity fetishism, in which the things that people produce, commodities, appear to have a life and movement of their own to which humans and their behavior merely adapt.

Commodity fetishism provides an example of what Engels called "false consciousness", which relates closely to the understanding of ideology. By "ideology", Marx and Engels meant ideas that reflect the interests of a particular class at a particular time in history, but which contemporaries see as universal and eternal. Marx and Engels's point was not only that such beliefs are at best half truths; they serve an important political function. Put another way, the control that one class exercises over the means of production includes not only the production of food or manufactured goods; it includes the production of ideas as well (this provides one possible explanation for why members of a subordinate class may hold ideas contrary to their own interests). An example of this sort of analysis is Marx's understanding of religion, summed up in a passage from the preface to his 1843 Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right:

Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people. The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions.—Karl Marx, Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right

Whereas his Gymnasium senior thesis argued that religion had as its primary social aim the promotion of solidarity,

here Marx sees the social function of religion in terms of highlighting

/ preserving political and economic status quo and inequality.

Marx's thoughts on labor were related to the primacy he gave to the economic relation in determining the society's past, present and future (economic determinism). Accumulation of capital shapes the social system. Social change, for Marx, was about conflict between opposing interests, driven, in the background, by economic forces. This became the inspiration for the body of works known as the conflict theory. In his evolutionary model of history, he argued that human history began with free, productive and creative work that was over time coerced and dehumanized, a trend most apparent under capitalism. Marx noted that this was not an intentional process; rather, no individual or even no state can go against the forces of economy.

The organization of society depends on means of production. Literally those things, like land, natural resources and technology, necessary for the production of material goods and the relations of production, in other words, the social relationships people enter into as they acquire and use the means of production. Together these compose the mode of production, and Marx distinguished historical eras in terms of distinct modes of production. Marx differentiated between base and superstructure, with the base (or substructure) referring to the economic system, and superstructure, to the cultural and political system. Marx regarded this mismatch between (economic) base and (social) superstructure as a major source of social disruption and conflict.

Despite Marx's stress on critique of capitalism and discussion of the new communist society

that should replace it, his explicit critique of capitalism is guarded,

as he saw it as an improved society compared to the past ones (slavery and feudal). Marx also never clearly discusses issues of morality and justice, although scholars agree that his work contained implicit discussion of those concepts.

Marx's view of capitalism was two sided. On one hand, Marx, in the 19th century's deepest critique of the dehumanizing aspects of this system, noted that defining features of capitalism include alienation, exploitation and recurring, cyclical depressions leading to mass unemployment; on the other hand capitalism is also characterized by "revolutionizing, industrializing and universalizing qualities of development, growth and progressivity" (by which Marx meant industrialization, urbanization, technological progress, increased productivity and growth, rationality and scientific revolution), that are responsible for progress. Marx considered the capitalist class to be one of the most revolutionary in history, because it constantly improved the means of production, more so than any other class in history, and was responsible for the overthrow of feudalism and its transition to capitalism. Capitalism can stimulate considerable growth because the capitalist can, and has an incentive to, reinvest profits in new technologies and capital equipment.

According to Marx capitalists take advantage of the difference between the labor market and the market for whatever commodity the capitalist can produce. Marx observed that in practically every successful industry input unit - costs are lower than output unit - prices. Marx called the difference "surplus value" and argued that this surplus value had its source in surplus labor, the difference between what it costs to keep workers alive and what they can produce. Marx's dual view of capitalism can be seen in his description of the capitalists: he refers to them as to vampires sucking worker's blood, but at the same time, he notes that drawing profit is "by no means an injustice" and that capitalists simply cannot go against the system. The true problem lies with the "cancerous cell" of capital, understood not as property or equipment, but the relations between workers and owners – the economic system in general.

At the same time, Marx stressed that capitalism was unstable, and prone to periodic crises. He suggested that over time, capitalists would invest more and more in new technologies, and less and less in labor. Since Marx believed that surplus value appropriated from labor is the source of profits, he concluded that the rate of profit would fall even as the economy grew. Marx believed that increasingly severe crises would punctuate this cycle of growth, collapse, and more growth. Moreover, he believed that in the long term this process would necessarily enrich and empower the capitalist class and impoverish the proletariat. In section one of The Communist Manifesto Marx describes feudalism, capitalism, and the role internal social contradictions play in the historical process:

We see then: the means of production and of exchange, on whose foundation the bourgeoisie built itself up, were generated in feudal society. At a certain stage in the development of these means of production and of exchange, the conditions under which feudal society produced and exchanged ... the feudal relations of property became no longer compatible with the already developed productive forces; they became so many fetters. They had to be burst asunder; they were burst asunder. Into their place stepped free competition, accompanied by a social and political constitution adapted in it, and the economic and political sway of the bourgeois class. A similar movement is going on before our own eyes ... The productive forces at the disposal of society no longer tend to further the development of the conditions of bourgeois property; on the contrary, they have become too powerful for these conditions, by which they are fettered, and so soon as they overcome these fetters, they bring order into the whole of bourgeois society, endanger the existence of bourgeois property.—Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto

Marx believed that those structural contradictions within capitalism necessitate its end, giving way to socialism, or a post - capitalistic, communist society:

The development of Modern Industry, therefore, cuts from under its feet the very foundation on which the bourgeoisie produces and appropriates products. What the bourgeoisie, therefore, produces, above all, are its own grave - diggers. Its fall and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable."—Karl Marx and Frederic Engels, The Communist Manifesto

Thanks to various processes overseen by capitalism, such as urbanization, the working class, the proletariat, should grow in numbers and develop a class consciousness, in time realizing that they have to change the system. Marx believed that if the proletariat were to seize the means of production, they would encourage social relations that would benefit everyone equally, abolishing exploiting class, and introduce a system of production less vulnerable to cyclical crises. Marx argued that capitalism will end through the organized actions of an international working class:

Communism is for us not a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality will have to adjust itself. We call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things. The conditions of this movement result from the premises now in existence."—Karl Marx, The German Ideology

In this new society the self - alienation would end, and humans would

be free to act without being bound by the labor market. It would be a democratic society, enfranchising the entire population.

In such a utopian world there would also be little if any need for a

state, whose goal was to enforce the alienation. He theorized that

between capitalism and the establishment of a socialist / communist

system, a dictatorship of the proletariat — a period where the working

class holds political power and forcibly socializes the means of

production — would exist. As he wrote in his "Critique of the Gotha

Program", "between capitalist and communist society

there lies the period of the revolutionary transformation of the one

into the other. Corresponding to this is also a political transition

period in which the state can be nothing but the revolutionary

dictatorship of the proletariat." While he allowed for the possibility of peaceful transition in some countries with strong democratic institutional structures (such as Britain, the US and the Netherlands),

he suggested that in other countries with strong centralized

state - oriented traditions, like France and Germany, the "lever of our

revolution must be force."

Marx married Jenny von Westphalen in 1843. Together had seven children, but partly owing to the poor living conditions they were forced to live in whilst in London, only three survived to adulthood. The children were: Jenny Caroline (m. Longuet; 1844 – 83); Jenny Laura (m. Lafargue; 1845 – 1911); Edgar (1847 – 1855); Henry Edward Guy ("Guido"; 1849 – 1850); Jenny Eveline Frances ("Franziska"; 1851 – 52); Jenny Julia Eleanor (1855 – 98) and one more who died before being named (July 1857). There are allegations that Marx also fathered a son, Freddy, out of wedlock by his housekeeper, Helene Demuth.

Marx frequently used pseudonyms, often when renting a house or flat,

apparently to make it harder for the authorities to track him down.

While in Paris, he used that of 'Monsieur Ramboz', whilst in London he

signed off his letters as 'A. Williams'. His friends referred to him as

'Moor', owing to his dark complexion and black curly hair, something

which they believed made him resemble the historical Moors of North

Africa, whilst he encouraged his children to call him 'Old Nick' and

'Charley'.

He also bestowed nicknames and pseudonyms on his friends and family as

well, referring to Friedrich Engels as 'General', his housekeeper Helene

as 'Lenchen' or 'Nym', while one of his daughters, Jennychen, was

referred to as 'Qui Qui, Emperor of China' and another, Laura, was known

as 'Kakadou' or 'the Hottentot'.

Marx is widely thought of as one of the most influential thinkers in history, who has had a significant influence on both world politics and intellectual thought, and in a 1999 BBC poll was voted the top "thinker of the millennium". Robert C. Tucker credits Marx with profoundly affecting ideas about history, society, economics, culture and politics, and the nature of social inquiry. Marx's biographer Francis Wheen considers the "history of the twentieth century" to be "Marx's legacy", whilst philosopher Peter Singer believes that Marx's impact can be compared with that of the founders of the two major world religions, Jesus Christ and Muhammad. Singer notes that "Marx's ideas brought about modern sociology, transformed the study of history, and profoundly affected philosophy, literature and the arts." Paul Ricœur calls Marx one of the masters of the "school of suspicion", alongside Friedrich Nietzsche and Sigmund Freud. Philip Stokes says that Marx's ideas led to him becoming "the darling of both European and American intellectuals up until the 1960s". Marx has influenced disciplines such as archaeology, anthropology, media studies, political science, theater, history, sociological theory, cultural studies, education, economics, geography, literary criticism, aesthetics, critical psychology, and philosophy.

In July 2005, 27.9% of listeners in a BBC Radio 4 series In Our Time poll selected Marx as their favorite thinker.

The reasons for Marx's widespread influence revolve around his ethical

message; a "morally empowering language of critique" against the

dominant capitalist society. No other body of work was so relevant to

the modern times, and at the same time, so outspoken about the need for

change.

In the political realm, Marx's ideas led to the establishment of

governments using Marxist thought to replace capitalism with communism

or socialism (or augment it with market socialism)

across much of the world, whilst his intellectual thought has heavily

influenced the academic study of the humanities and the arts.

Followers of Marx have drawn on his work to propose grand, cohesive theoretical outlooks dubbed "Marxism". This body of works has had significant influence on both the political and scientific scenes. Nevertheless, Marxists have frequently debated amongst themselves over how to interpret Marx's writings and how to apply his concepts to their contemporary events and conditions. The legacy of Marx's thought has become bitterly contested between numerous tendencies which each see themselves as Marx's most accurate interpreters, including (but not limited to) Leninism, Stalinism, Trotskyism, Maoism, Luxemburgism, and libertarian Marxism. In academic Marxism, various currents have developed as well, often under influence of other views, resulting in structuralist Marxism, historical Marxism, phenomenological Marxism, Analytical Marxism and Hegelian Marxism.

Moreover, there is a distinction between "Marxism" and "what Marx believed"; for example, shortly before he died in 1883, Marx wrote a letter to the French workers' leader Jules Guesde, and to his own son - in - law Paul Lafargue, accusing them of "revolutionary phrase - mongering" and of lack of faith in the working class. After the French party split into a reformist and revolutionary party, some accused Guesde (leader of the latter) of taking orders from Marx; Marx remarked to Lafargue, "if that is Marxism, then I am not a Marxist" (in a letter to Engels, Marx later accused Guesde of being a "Bakuninist").

Marx is typically cited, along with Émile Durkheim and Max Weber, as one of the three principal architects of modern social science. In contrast to philosophers, Marx offered theories that could often be tested with the scientific method. Both Marx and Auguste Comte set out to develop scientifically justified ideologies in the wake of European secularization and new developments in the philosophies of history and science. Whilst Marx, working in the Hegelian tradition, rejected Comtean sociological positivism, in attempting to develop a science of society he nevertheless came to be recognized as a founder of sociology as the word gained wider meaning. In modern sociological theory, Marxist sociology is recognized as one of the main classical perspectives. For Isaiah Berlin, Marx may be regarded as the "true father" of modern sociology, "in so far as anyone can claim the title."

While many Marxist concepts are still of importance for modern social science, some specific predictions Marx made have been shown to be unlikely. Marx is often criticized for expecting a wave of socialist revolutions, originating in the most highly industrialized countries, to overturn capitalism. However others, pointing to Marx's encounter with late 19th century Russian populism and Marx and Engels's preface to the second Russian edition of the Manifesto of the Communist Party (1882), have argued that Marx evinced a growing conviction in his late writings that revolution could in fact emerge first in Russia. Marx predicted the eventual fall of capitalism, to be replaced by socialism, yet since the late 20th century state socialism is in retreat, as the Soviet Union collapsed, and the People's Republic of China shifted towards a market economy. Additionally, his argument that profits are generated only through surplus labor has been challenged by the counterclaim that profits also come from investments in human capital and technology. Marx correctly predicted that over time, inequality would grow but he also believed that this would mean growing impoverishment of the growing worker class, increasingly exploited by the capitalists. The latter has also come true; as in the developed world, through liberal reforms, trade unions won many concessions, improving the situation of the workers (something that Marx considered very unlikely); in the more populated parts of the world such as Africa, India, and China the populations continue to grow and all the industry is moving there if it has not already established itself in the last two decades. Worldwide poverty has increased since the end of the 19th century especially considering that the richest are richer than ever but the poor have remained at the same level and the percentage has risen in the last 30 years. (Scholars have debated whether Marx's comments about the proletariat can be analyzed in the context of the working class). In addition to specific predictions, certain of Marx's theories, such as his labor theory of value, have also been criticized. However, in the wake of the economic crisis of 2008, Greek government debt crisis, and European sovereign debt crisis some thinkers like Terry Eagleton, David Harvey, and David McNally have given renewed impetus to the debate on whether Marx was right that capitalism inherently tends towards crisis (which Marx discussed as the "contradictions of capital").

While Marxist thought may be used to empower marginalized and

dispossessed people, it has also been used to prop up governments who

have utilized violence to remove those seen as impeding the revolution.

In some instances, his ultimate goals have been used as justification

for the end justifies the means logic. Moreover, contrary to his goal, his ideas have been used to promote dogmatism and intolerance. Polish historian Andrzej Walicki

noted that Marx's and Engels's theory was the "theory of freedom", but a

theory that, at the height of its influence, was used to legitimize the

totalitarian socialist state of the Soviet Union. This abuse of Marx's thought is perhaps most clearly exemplified in Stalinist

Marxism, described by critics as the "most widespread and successful

form of mass indoctrination... a masterly achievement in transforming

Marxism into the official ideology of a consistently totalitarian

state."

The controversy is further fueled as some left wing theorists have

tried to shield Marxism from any connection to the Soviet regime.

Lastly, the undue focus on the Marxist thought in the former Eastern

Bloc, often forbidding social science arguments from outside the Marxist

perspective, led to a backlash against Marxism after the revolutions of 1989. In one example, references to Marx drastically decreased in Polish sociology after the fall of the revolutionary socialist governments, and two

major research institutions which advocated the Marxist approach to

sociology were closed.

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English philosopher, biologist, sociologist, and prominent classical liberal political theorist of the Victorian era.

Spencer developed an all - embracing conception of evolution as the progressive development of the physical world, biological organisms, the human mind, and human culture and societies. He was "an enthusiastic exponent of evolution" and even "wrote about evolution before Darwin did." As a polymath, he contributed to a wide range of subjects, including ethics, religion, anthropology, economics, political theory, philosophy, biology, sociology and psychology. During his lifetime he achieved tremendous authority, mainly in English speaking academia. "The only other English philosopher to have achieved anything like such widespread popularity was Bertrand Russell, and that was in the 20th century." Spencer was "the single most famous European intellectual in the closing decades of the nineteenth century" but his influence declined sharply after 1900; "Who now reads Spencer?" asked Talcott Parsons in 1937.

Spencer is best known for coining the concept "survival of the fittest", which he did in Principles of Biology (1864), after reading Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species.

This term strongly suggests natural selection, yet as Spencer extended

evolution into realms of sociology and ethics, he also made use of

Lamarckism.

Herbert Spencer was born in Derby, England, on 27 April 1820, the son of William George Spencer (generally called George). Spencer’s father was a religious dissenter who drifted from Methodism to Quakerism, and who seems to have transmitted to his son an opposition to all forms of authority. He ran a school founded on the progressive teaching methods of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi and also served as Secretary of the Derby Philosophical Society, a scientific society which had been founded in the 1790s by Erasmus Darwin, the grandfather of Charles.

Spencer was educated in empirical science by his father, while the members of the Derby Philosophical Society introduced him to pre-Darwinian concepts of biological evolution, particularly those of Erasmus Darwin and Jean - Baptiste Lamarck. His uncle, the Reverend Thomas Spencer, vicar of Hinton Charterhouse near Bath, completed Spencer’s limited formal education by teaching him some mathematics and physics, and enough Latin to enable him to translate some easy texts. Thomas Spencer also imprinted on his nephew his own firm free trade and anti - statist political views. Otherwise, Spencer was an autodidact who acquired most of his knowledge from narrowly focused readings and conversations with his friends and acquaintances.

As both an adolescent and a young man Spencer found it difficult to settle to any intellectual or professional discipline. He worked as a civil engineer during the railway boom of the late 1830s, while also devoting much of his time to writing for provincial journals that were nonconformist in their religion and radical in their politics. From 1848 to 1853 he served as sub-editor on the free trade journal The Economist, during which time he published his first book, Social Statics (1851), which predicted that humanity would eventually become completely adapted to the requirements of living in society with the consequential withering away of the state.

Its publisher, John Chapman, introduced Spencer to his salon which was attended by many of the leading radical and progressive thinkers of the capital, including John Stuart Mill, Harriet Martineau, George Henry Lewes and Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot), with whom he was briefly romantically linked. Spencer himself introduced the biologist Thomas Henry Huxley, who would later win fame as 'Darwin’s Bulldog' and who remained his lifelong friend. However it was the friendship of Evans and Lewes that acquainted him with John Stuart Mill’s A System of Logic and with Auguste Comte’s positivism and which set him on the road to his life’s work. He strongly disagreed with Comte.

The first fruit of his friendship with Evans and Lewes was Spencer's second book, Principles of Psychology, published in 1855, which explored a physiological basis for psychology. The book was founded on the fundamental assumption that the human mind was subject to natural laws and that these could be discovered within the framework of general biology. This permitted the adoption of a developmental perspective not merely in terms of the individual (as in traditional psychology), but also of the species and the race. Through this paradigm, Spencer aimed to reconcile the associationist psychology of Mill’s Logic, the notion that human mind was constructed from atomic sensations held together by the laws of the association of ideas, with the apparently more 'scientific' theory of phrenology, which located specific mental functions in specific parts of the brain.

Spencer argued that both these theories were partial accounts of the truth: repeated associations of ideas were embodied in the formation of specific strands of brain tissue, and these could be passed from one generation to the next by means of the Lamarckian mechanism of use - inheritance. The Psychology, he believed, would do for the human mind what Isaac Newton had done for matter. However, the book was not initially successful and the last of the 251 copies of its first edition was not sold until June 1861.

Spencer's interest in psychology derived from a more fundamental concern which was to establish the universality of natural law.

In common with others of his generation, including the members of

Chapman's salon, he was possessed with the idea of demonstrating that it

was possible to show that everything in the universe — including human

culture, language and morality — could be explained by laws of universal

validity. This was in contrast to the views of many theologians of the

time who insisted that some parts of creation, in particular the human

soul, were beyond the realm of scientific investigation. Comte's Système de Philosophie Positive

had been written with the ambition of demonstrating the universality of

natural law, and Spencer was to follow Comte in the scale of his

ambition. However, Spencer differed from Comte in believing it was

possible to discover a single law of universal application which he

identified with progressive development and was to call the principle of

evolution.

In 1858 Spencer produced an outline of what was to become the System of Synthetic Philosophy. This immense undertaking, which has few parallels in the English language, aimed to demonstrate that the principle of evolution applied in biology, psychology, sociology (Spencer appropriated Comte's term for the new discipline) and morality. Spencer envisaged that this work of ten volumes would take twenty years to complete; in the end it took him twice as long and consumed almost all the rest of his long life.

Despite Spencer's early struggles to establish himself as a writer, by the 1870s he had become the most famous philosopher of the age. His works were widely read during his lifetime, and by 1869 he was able to support himself solely on the profit of book sales and on income from his regular contributions to Victorian periodicals which were collected as three volumes of Essays. His works were translated into German, Italian, Spanish, French, Russian, Japanese and Chinese, and into many other languages and he was offered honors and awards all over Europe and North America. He also became a member of the Athenaeum, an exclusive Gentleman's Club in London open only to those distinguished in the arts and sciences, and the X Club, a dining club of nine founded by T. H. Huxley that met every month and included some of the most prominent thinkers of the Victorian age (three of whom would become presidents of the Royal Society).

Members included physicist - philosopher John Tyndall and Darwin's cousin, the banker and biologist Sir John Lubbock. There were also some quite significant satellites such as liberal clergyman Arthur Stanley, the Dean of Westminster; and guests such as Charles Darwin and Hermann von Helmholtz were entertained from time to time. Through such associations, Spencer had a strong presence in the heart of the scientific community and was able to secure an influential audience for his views. Despite his growing wealth and fame he never owned a house of his own.

The last decades of Spencer's life were characterized by growing

disillusionment and loneliness. He never married, and after 1855 was a

perpetual hypochondriac who complained endlessly of pains and maladies

that no physician could diagnose.

By the 1890s his readership had begun to desert him while many of his

closest friends died and he had come to doubt the confident faith in

progress that he had made the centerpiece of his philosophical system.

His later years were also ones in which his political views became

increasingly conservative. Whereas Social Statics had been the

work of a radical democrat who believed in votes for women (and even for

children) and in the nationalization of the land to break the power of

the aristocracy, by the 1880s he had become a staunch opponent of female

suffrage and made common cause with the landowners of the Liberty and

Property Defence League against what they saw as the drift towards

'socialism' of elements (such as Sir William Harcourt) within the

administration of William Ewart Gladstone — largely

against the opinions of Gladstone himself. Spencer's political views

from this period were expressed in what has become his most famous work,

The Man versus the State.

The exception to Spencer's growing conservatism was that he remained throughout his life an ardent opponent of imperialism and militarism. His critique of the Boer War was especially scathing, and it contributed to his declining popularity in Britain.

Spencer also invented a precursor to the modern paper clip, though it looked more like a modern cotter pin. This "binding - pin" was distributed by Ackermann & Company. Spencer shows drawings of the pin in Appendix I (following Appendix H) of his autobiography along with published descriptions of its uses.

In 1902, shortly before his death, Spencer was nominated for the Nobel Prize for literature.

He continued writing all his life, in later years often by dictation,

until he succumbed to poor health at the age of 83. His ashes are

interred in the eastern side of London's Highgate Cemetery facing Karl

Marx's grave. At Spencer's funeral the Indian nationalist leader Shyamji Krishnavarma announced a donation of £1,000 to establish a lectureship at Oxford University in tribute to Spencer and his work.

The basis for Spencer's appeal to many of his generation was that he appeared to offer a ready - made system of belief which could substitute for conventional religious faith at a time when orthodox creeds were crumbling under the advances of modern science. Spencer's philosophical system seemed to demonstrate that it was possible to believe in the ultimate perfection of humanity on the basis of advanced scientific conceptions such as the first law of thermodynamics and biological evolution.

In essence Spencer's philosophical vision was formed by a combination of deism and positivism. On the one hand, he had imbibed something of eighteenth century deism from his father and other members of the Derby Philosophical Society and from books like George Combe's immensely popular The Constitution of Man (1828). This treated the world as a cosmos of benevolent design, and the laws of nature as the decrees of a 'Being transcendentally kind.' Natural laws were thus the statutes of a well governed universe that had been decreed by the Creator with the intention of promoting human happiness. Although Spencer lost his Christian faith as a teenager and later rejected any 'anthropomorphic' conception of the Deity, he nonetheless held fast to this conception at an almost sub-conscious level. At the same time, however, he owed far more than he would ever acknowledge to positivism, in particular in its conception of a philosophical system as the unification of the various branches of scientific knowledge. He also followed positivism in his insistence that it was only possible to have genuine knowledge of phenomena and hence that it was idle to speculate about the nature of the ultimate reality. The tension between positivism and his residual deism ran through the entire System of Synthetic Philosophy.

Spencer followed Comte in aiming for the unification of scientific truth; it was in this sense that his philosophy aimed to be 'synthetic.' Like Comte, he was committed to the universality of natural law, the idea that the laws of nature applied without exception, to the organic realm as much as to the inorganic, and to the human mind as much as to the rest of creation. The first objective of the Synthetic Philosophy was thus to demonstrate that there were no exceptions to being able to discover scientific explanations, in the form of natural laws, of all the phenomena of the universe. Spencer’s volumes on biology, psychology and sociology were all intended to demonstrate the existence of natural laws in these specific disciplines. Even in his writings on ethics, he held that it was possible to discover ‘laws’ of morality that had the status of laws of nature while still having normative content, a conception which can be traced to Comte’s Constitution of Man.

The second objective of the Synthetic Philosophy was to show that

these same laws led inexorably to progress. In contrast to Comte, who

stressed only the unity of scientific method, Spencer sought the

unification of scientific knowledge in the form of the reduction of all

natural laws to one fundamental law, the law of evolution. In this

respect, he followed the model laid down by the Edinburgh publisher Robert Chambers in his anonymous Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844). Although often dismissed as a lightweight forerunner of Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species, Chambers’ book was in reality a program for the unification of science which aimed to show that Laplace’s nebular hypothesis

for the origin of the solar system and Lamarck’s theory of species

transformation were both instances (in Lewes' phrase) of 'one

magnificent generalization of progressive development.' Chambers was

associated with Chapman’s salon and his work served as the

unacknowledged template for the Synthetic Philosophy.

The first clear articulation of Spencer’s evolutionary perspective occurred in his essay, 'Progress: Its Law and Cause', published in Chapman's Westminster Review in 1857, and which later formed the basis of the First Principles of a New System of Philosophy (1862). In it he expounded a theory of evolution which combined insights from Samuel Taylor Coleridge's essay 'The Theory of Life' — itself derivative from Friedrich von Schelling's Naturphilosophie — with a generalization of von Baer’s law of embryological development. Spencer posited that all structures in the universe develop from a simple, undifferentiated, homogeneity to a complex, differentiated, heterogeneity, while being accompanied by a process of greater integration of the differentiated parts. This evolutionary process could be found at work, Spencer believed, throughout the cosmos. It was a universal law, applying to the stars and the galaxies as much as to biological organisms, and to human social organization as much as to the human mind. It differed from other scientific laws only by its greater generality, and the laws of the special sciences could be shown to be illustrations of this principle.

This attempt to explain the evolution of complexity was radically different from that to be found in Darwin’s Origin of Species

which was published two years later. Spencer is often, quite

erroneously, believed to have merely appropriated and generalized

Darwin’s work on natural selection. But although after reading Darwin's

work he coined the phrase 'survival of the fittest' as his own term for

Darwin's concept,

and is often misrepresented as a thinker who merely applied the

Darwinian theory to society, he only grudgingly incorporated natural

selection into his preexisting overall system. The primary mechanism of

species transformation that he recognized was Lamarckian

use - inheritance which posited that organs are developed or are

diminished by use or disuse and that the resulting changes may be

transmitted to future generations. Spencer believed that this

evolutionary mechanism was also necessary to explain 'higher' evolution,

especially the social development of humanity. Moreover, in contrast to

Darwin, he held that evolution had a direction and an end point, the

attainment of a final state of equilibrium. He tried to apply the theory

of biological evolution to sociology. He proposed that society was the

product of change from lower to higher forms, just as in the theory of

biological evolution, the lowest forms of life are said to be evolving

into higher forms. Spencer claimed that man's mind had evolved in the

same way from the simple automatic responses of lower animals to the

process of reasoning in the thinking man. Spencer believed in two kinds

of knowledge: knowledge gained by the individual and knowledge gained by

the race. Intuition, or knowledge learned unconsciously, was the

inherited experience of the race.

Spencer read with excitement the original positivist sociology of Auguste Comte. A philosopher of science, Comte had proposed a theory of sociocultural evolution that society progresses by a general law of three stages. Writing after various developments in biology, however, Spencer rejected what he regarded as the ideological aspects of Comte's positivism, attempting to reformulate social science in terms of evolutionary biology. One might broadly describe Spencer's sociology as socially Darwinistic (though strictly speaking he was a proponent of Lamarckism rather than Darwinism).

The evolutionary progression from simple, undifferentiated homogeneity to complex, differentiated heterogeneity was exemplified, Spencer argued, by the development of society. He developed a theory of two types of society, the militant and the industrial, which corresponded to this evolutionary progression. Militant society, structured around relationships of hierarchy and obedience, was simple and undifferentiated; industrial society, based on voluntary, contractually assumed social obligations, was complex and differentiated. Society, which Spencer conceptualized as a 'social organism' evolved from the simpler state to the more complex according to the universal law of evolution. Moreover, industrial society was the direct descendant of the ideal society developed in Social Statics, although Spencer now equivocated over whether the evolution of society would result in anarchism (as he had first believed) or whether it pointed to a continued role for the state, albeit one reduced to the minimal functions of the enforcement of contracts and external defense.

Though Spencer made some valuable contributions to early sociology, not least in his influence on structural functionalism,

his attempt to introduce Lamarckian or Darwinian ideas into the realm

of social science was unsuccessful. It was considered by many,

furthermore, to be actively dangerous. Hermeneuticians of the period, such as Wilhelm Dilthey, would pioneer the distinction between the natural sciences (Naturwissenschaften) and human sciences (Geisteswissenschaften).

In the 1890s, Émile Durkheim established formal academic sociology with

a firm emphasis on practical social research. By the turn of the 20th

century the first generation of German sociologists, most notably Max

Weber, had presented methodological antipositivism.

The end point of the evolutionary process would be the creation of 'the perfect man in the perfect society' with human beings becoming completely adapted to social life, as predicted in Spencer’s first book. The chief difference between Spencer’s earlier and later conceptions of this process was the evolutionary timescale involved. The psychological — and hence also the moral — constitution which had been bequeathed to the present generation by our ancestors, and which we in turn would hand on to future generations, was in the process of gradual adaptation to the requirements of living in society. For example, aggression was a survival instinct which had been necessary in the primitive conditions of life, but was maladaptive in advanced societies. Because human instincts had a specific location in strands of brain tissue, they were subject to the Lamarckian mechanism of use - inheritance so that gradual modifications could be transmitted to future generations. Over the course of many generations the evolutionary process would ensure that human beings would become less aggressive and increasingly altruistic, leading eventually to a perfect society in which no one would cause another person pain.

However, for evolution to produce the perfect individual it was necessary for present and future generations to experience the 'natural' consequences of their conduct. Only in this way would individuals have the incentives required to work on self - improvement and thus to hand an improved moral constitution to their descendants. Hence anything that interfered with the 'natural' relationship of conduct and consequence was to be resisted and this included the use of the coercive power of the state to relieve poverty, to provide public education, or to require compulsory vaccination. Although charitable giving was to be encouraged even it had to be limited by the consideration that suffering was frequently the result of individuals receiving the consequences of their actions. Hence too much individual benevolence directed to the 'undeserving poor' would break the link between conduct and consequence that Spencer considered fundamental to ensuring that humanity continued to evolve to a higher level of development.