<Back to Index>

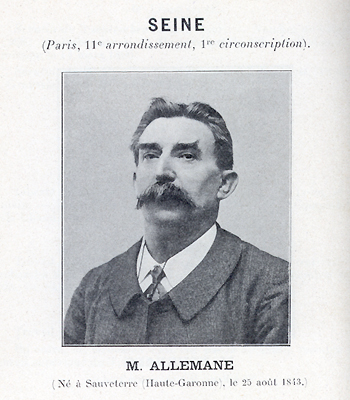

- Leader of the Socialist - Revolutionary Workers' Party Jean Allemane, 1843

- Member of the Chamber of Deputies Marie Édouard Vaillant, 1840

PAGE SPONSOR

Jean Allemane (1843, Sauveterre - de - Comminges, Haute - Garonne – 1935) was a French socialist politician, veteran of the Paris Commune of 1871, pioneer of syndicalism, leader of the Socialist - Revolutionary Workers' Party (POSR) and co-founder of the unified French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO) in 1905. He was a deputy in the National Assembly of the Third French Republic.

Jean Allemane was born into a working class family in Sauveterre - de - Comminges (Haute - Garonne) in southern France. In 1853 he came to Paris with his parents and was apprenticed as a printer. The hardship of working conditions, the republican sympathies of his family and the writings of Pierre - Joseph Proudhon conspired to radicalize Allemane early on. As a teenager he became involved in trade union activity, which was still illegal in France (unions were not legalized until 1906). In 1862, aged 19, he was arrested for his role in organizing the first typesetters' strike in Paris. Subsequently he helped found the typesetters' union. Despite his youth, Allemane played an important role in the emerging French syndicalist movement and emphasized the need for workers to form their own organizations, independent of bourgois radicals.

In 1870 Allemane served in the Parisian National Guard, where he

became a corporal. In this capacity he participated in the uprising of

the Paris Commune at the end of the Franco - Prussian War of 1871. Although he welcomed the fall of Napoléon III, he mistrusted the conservative republicans around Adolphe Thiers

who replaced him. In the Commune, Allemane sympathized with the

Proudhonist faction. Allemane participated actively in the fighting.

After the suppression of the Commune, he went into hiding but was

captured, and in 1872, he was sentenced to hard labor in perpetuity and

banished to the penal colony of New Caledonia. In 1876 he made an

unsuccessful attempt to escape. In 1878, he was ordered to participate

in suppressing a revolt of the native population but refused. This led

to further penalties. However, in 1879, a general amnesty enabled

Allemane to return to France.

In 1880, Allemane became a typesetter at the radical newspaper L'Intransigeant, founded by the republican Henri Rochefort. That year, he became a founding member of the French Workers' Party (POF), founded by Jules Guesde and Paul Lafargue. Guesde and Lafargue were by then Marxists (and Lafargue was Marx' son - in - law), but the POF was not yet a homogeneous Marxist party, and Allemane sympathized with non - Marxist, syndicalist and Proudhonist tendencies. In 1882, he supported the 'Possibilist' Paul Brousse in his conflict with Guesde. Like Allemane and Guesde himself, Brousse had been a Communard and had once sympathized with anarchism, but in the 1880s, the party he led - the Federation of the Socialist Workers of France (FTSF) - adopted an increasingly reformist course. Allemane became increasingly disenchanted with this. In his own journal, Parti Ouvrier, he called for a more radical course and advocated syndicalist ideas such as a general strike that was to precipitate a revolution, direct action (sabotage, strikes, factory occupations) and the formation of separate proletarian organizations not subject to bourgeois leadership.

During the Boulangist crisis of 1886 - 89, when the popular nationalist General Boulanger seemed to threaten a coup d'état, Allemane became one of the most vocal defenders of the Republic. This temporarily re-enforced his alliance with Brousse and with reformist socialists and republicans who opposed the general. (By contrast, the Guesdists and the Blanquists maintained an attitude of neutrality between the 'bourgeois general' and the 'bourgeois republic'.) However, once the crisis had passed, Allemane's radicalism put him at odds with the Possibilists and reformists. In 1890 he was expelled from the FTSF and formed his own party, the French Socialist - Revolutionary Workers' Party (Parti Ouvrier Socialiste - Révolutionnaire), which called for a general strike, worked closely with the trade union movement and rejected bourgeois parliamentary democracy as insufficiently democratic. Nevertheless, the Allemanists, as they were called, stood for elections, and Allemane later became a deputy in the National Assembly. The Guesdists, as orthodox Marxists, strongly criticized Allemanism: 'general strike is general nonsense' was their slogan, and trade unions should be placed firmly under the political leadership of a socialist party. By contrast, the Allemanists insisted on the autonomy of the trade unions and saw the socialist party merely as the political representative of the extra - parliamentary workers' movement.

Allemane's support of the labor movement and his involvement in the CGT translated into working class support for his party. In 1901, he was first elected to the Chamber of Deputies, together with several other representatives of the POSR. He was subsequently elected again in 1906. During the Dreyfus affair, Allemane was a staunch defender of the Jewish officer, who, it turned out, was unjustly accused of treason. He denounced the rising tide of anti - Semitism. Again, this aligned him with the Broussists and reformist socialists around Jean Jaurès. (The Guesdists and Blanquists regarded the Dreyfus Affair as a quarrel within the bourgeoisie.) In 1899, the Independent Socialist Alexandre Millerand precipitated a fierce controversy in French and European socialism by joining a bourgeois republican cabinet - something no socialist had done since Louis Blanc's ill fated participation in the Provisional Government of the Second Republic in 1848. The controversy over Millerandism coincided with the Revisionist controversy in German Social Democracy and with the controversy over 'Economism' among Russian Marxists. Revolutionary socialists like Guesde and Édouard Vaillant saw all three phenomena as a betrayal of the working class; Jaurès and the reformists supported Millerand, albeit reluctantly. Allemane took an intermediate position, skeptical of participation in bourgeois cabinets but willing to support reformist social legislation. Eventually, Millerand left the socialist party altogether.

Despite the quarrel over Millerandism, the Second International was putting pressure on the many French socialist organizations to come together. In 1902, a first attempt at unification failed, because the differences between centralists and federalists, revolutionaries and reformists, were still too great. The centralist and revolutionary POF of Guesde united with Vaillant's Blanquist Socialist - Revolutionary Party (France) and with the small Revolutionary Communist Alliance (ACR), which had splintered off from Allemane's POSR. These groups formed the Socialist Party of France (PSdF). Meanwhile, Allemane's POSR joined with Brousse's FTSF and the Independent Socialists of Jean Jaurès to form the French Socialist Party (PSF). The two rival socialist parties were finally merged in 1905 into the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO Party). Allemane served as a deputy for the SFIO from 1906 to 1910, representing the XIth arrondissement of Paris. Even as deputy, Allemane maintained his work as a printer and founded a printers' co-operative called La Productrice, which serve as a socialist print shop. In 1910, he published his Memoirs of a Communard.

The outbreak of World War I

bitterly divided the French socialists (as it did the socialists of

most countries). Allemane had been a staunch opponent of militarism in

his previous writings, but in 1914, he supported war 'in defense of the

nation'. Anti - war critics on the left saw this as a grave betrayal.

However, after the war, Allemane turned once again to the left. Already

in 1917, he had welcomed the Russian Revolution. Although he was skeptical of Leninism and had never really embraced Marxism, he accepted the October Revolution.

In 1920, at its 18th Congress in Tours, the SFIO split over the

question whether to remain in the Second International or join Lenin's

new Third International.

The majority voted to join the Third International and henceforth

called itself 'French Section of the Communist International',

subsequently renamed French Communist Party

(PCF). Allemane voted with the majority for adhesion to the Third

International, because its radicalism appealed to him. Nevertheless, he

did not join the PCF. Instead, in the 1920s, he flirted with the

National Socialist party of Gustave Hervé

(formerly an anti - militarist socialist but, since 1914, a staunch

nationalist). This group sought to unite socialists who had taken a

'patriotic' position during the First World War, but it also attracted

old Boulangist and anti - Dreyfusard elements, as well as anti - Marxist

syndicalists. In the course of the 1920s, this party developed more and

more in a fascist

direction. Allemane, however, never actually played a role in this

party. Instead, in his last years he concentrated on the activities of

his lodge of Free Masons. He died in 1935 at Herblay in Seine - et - Oise.

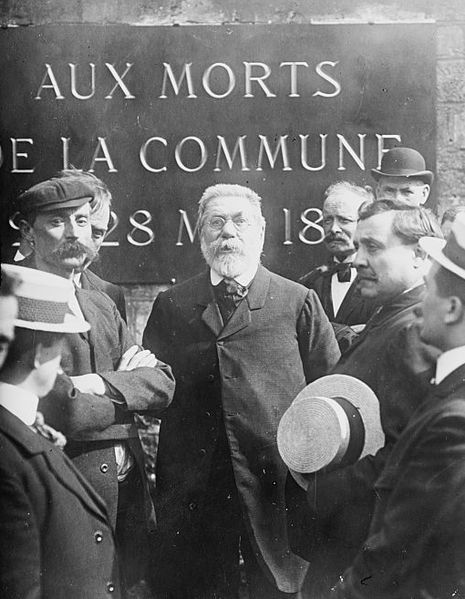

Marie Édouard Vaillant (26 January 1840–18 December 1915) was a French politician.

Born in Vierzon, Cher, son of a lawyer, Édouard Vaillant studied engineering at the École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures, graduating in 1862, and then law at the Sorbonne. In Paris he knew Charles Longuet, Louis - Auguste Rogeard and Jules Vallès. A reader of Joseph Proudhon writings, he met Proudhon, and joined the International Workingmen's Association.

He went to study in Germany in 1866. At the outbreak of the Franco - Prussian War in 1870 he returned to Paris. It was during the Siege of Paris that Vaillant met Auguste Blanqui. Vaillant opposed the Government of National Defense, and took part in the revolts on 31 October 1870 and 22 January 1871.

He was one of the four editors of the Affiche Rouge (red poster) calling for the creation of the Paris Commune. In the elections of February 1871 he stood as a revolutionary socialist candidate for the National Assembly but was not elected. In March 1871 he was elected by the XXe arrondissement to the council of the Commune where he oversaw work on education.

Following the bloody suppression of the Commune in late May 1871, Vaillant fled France for Great Britain where he was part of the Blanquist tendency of the First International. He was sentenced to death in absentia in July 1872 and did not return to France until the general amnesty of 1880.

Active in socialist politics, Vaillant was elected to the Chamber of Deputies in 1893, representing the XXe arrondissement. Although he had earlier been a convinced revolutionary, in the Chamber he generally followed a middle ground between the "revolutionaries" represented by Jules Guesde and the "reformists" represented by Jean Jaurès. He was among the founder members of the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO), a socialist party uniting revolutionary and reformist groups.

Vaillaint supported a general strike to prevent French participation in the First World War, but following the assassination of Jaurès and the outbreak of war, he joined the majority of socialists in supporting the Union sacrée and harshly criticized pacifist members of the SFIO in his speeches.

Édouard Vaillant died in Paris on 18 December 1915. Schools in his birthplace of Vierzon, and in Gennevilliers, are named in his honor.