<Back to Index>

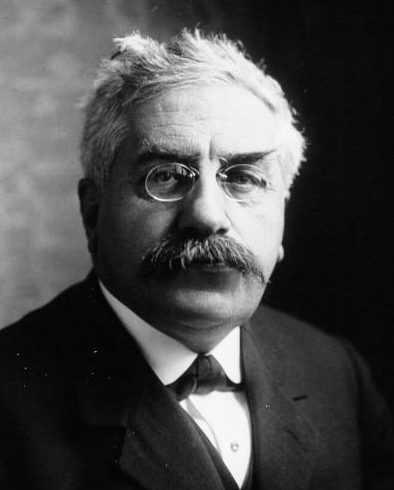

- Président de la République Française Alexandre Millerand, 1859

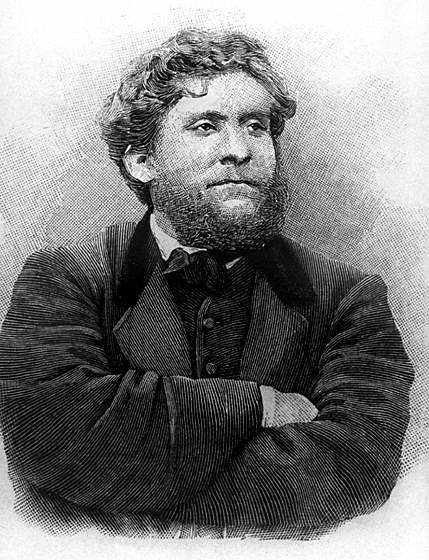

- Leader of the French Socialist Party Jean Léon Jaurès, 1859

PAGE SPONSOR

Alexandre Millerand (1859 – 1943) was a French socialist politician. He was President of France from 23 September 1920 to 11 June 1924 and Prime Minister of France 20 January to 23 September 1920. His participation in Waldeck - Rousseau's cabinet at the turn of the 19th to 20th century, alongside the marquis de Galliffet who had directed the repression of the 1871 Paris Commune, sparked a debate in the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO) and in the Second International about the participation of socialists in "bourgeois governments".

Born in Paris, he was educated for the Bar, and made his reputation by his defense, in company with Georges Laguerre, of Ernest Roche and Duc - Quercy, the instigators of the strike at Decazeville in 1883; he then took Laguerre's place on Georges Clemenceau's paper, La Justice. He was elected to the Chamber of Deputies for the Seine département in 1885 as a Radical Socialist. He was associated with Clemenceau and Camille Pelletan as an arbitrator in the Carmaux strike (1892). He had long had the ear of the Chamber in matters of social legislation, and after the Panama scandals had discredited so many politicians his influence grew.

He was chief of the Socialist faction (the Parti Socialiste de France in 1899), a group which then mustered sixty members, and edited until 1896 their organ in the press, La Petite République. His program included the collective ownership of the means of production and the international association of labor, but, when in June 1899 he entered Pierre Waldeck - Rousseau's cabinet of "republican defense" as Minister of Commerce, he limited himself to practical reforms, devoting his attention to the improvement of the mercantile marine, to the development of trade, of technical education, of the postal system, and to the amelioration of the conditions of labor. Labor questions were entrusted to a separate department, the Direction du Travail, and the pension and insurance office was also raised to the status of a "direction".

As labor minister, Millerand was responsible for the introduction of a wide range of reforms, including the reduction in the maximum workday from 11 to 10 hours in 1904, the introduction of an 8 hour workday for postal employees, the prescribing of maximum hours and minimum wages for all work undertaken by public authorities, the bringing of worker’s representatives into the Conseil supérieur de travail, the establishment of arbitration tribunals and inspectors of labor, and the creation of a labor section inside his Ministry of commerce to tackle the problem of social insurance.

The introduction of trade union representatives on the Supreme Labor Council, the organization of local labor councils, and the instructions to factory inspectors to put themselves in communication with the councils of the trade unions, were valuable concessions to labor, and he further secured the rigorous application of earlier laws devised for the protection of the working class. His name was especially associated with a project for the establishment of old age pensions, which became law in 1905. In 1898, he became editor of La Lanterne.

His influence with the far left had already declined, for it was said that his departure from the true Marxist tradition had disintegrated the party. He was expelled from the group, and continued to move to the right, being appointed Prime Minister by the conservative President Paul Deschanel.

When Deschanel had to resign later that year due to his mental disorder, Millerand emerged as a compromise candidate for President between the Bloc National and the remnants of the Bloc des gauches. Millerand appointed Georges Leygues, a politician with a long career of ministerial office, as Prime Minister and attempted to strengthen the executive powers of the Presidency. This move was resisted in the Chamber of Deputies and the French Senate, and Millerand was forced to appoint a stronger figure, Aristide Briand. Briand's appointment was welcomed by both left and right, although the Socialists and the left wing of the Radical Party did not join his government. However, Millerand dismissed Briand after just a year, and appointed the conservative republican Raymond Poincaré.

Millerand was accused of favoring conservatives in spite of the traditional neutrality of French Presidents and the composition of the legislature. On 14 July 1922, Millerand escaped an assassination attempt by Gustave Bouvet, a young French anarchist. Two years later, Millerand resigned in the face of growing conflict between the elected legislature and the office of the President, following the victory of the Cartel des Gauches. Gaston Doumergue, who was the president of the Senate at the time, was chosen to replace Millerand.

Alexandre Millerand died in 1943 at Versailles, and was interred in the Passy Cemetery.

Jean Léon Jaurès (full name Auguste Marie Joseph Jean Léon Jaurès; 3 September 1859 – 31 July 1914) was a French Socialist leader. Initially an Opportunist Republican, he evolved into one of the first social democrats, becoming the leader, in 1902, of the French Socialist Party, which opposed Jules Guesde's revolutionary Socialist Party of France. The two parties merged in 1905 in the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO). An anti - militarist, Jaurès was assassinated at the outbreak of World War I, and remains one of the main historical figures of the French Left.

The son of an unsuccessful businessman and farmer, Jean Jaurès was born in Castres (Tarn), in a modest French provincial bourgeois family. He was the first cousin once removed of the admiral and senator Benjamin Jaurès, who was named Minister of the Navy and Colonies in 1889, and of the admiral Charles Jaurès. His younger brother, Louis, also became an admiral and a Republican - Socialist deputy.

A brilliant student, Jaurès was educated at the Lycée Louis - le - Grand in Paris and admitted first at the École normale supérieure, in philosophy, in 1878, ahead of Henri Bergson. He obtained his agrégation of philosophy in 1881, ending up third, and then taught philosophy for two years at the lycée of Albi, before lecturing at the University of Toulouse. He was elected Republican deputy for the département of Tarn in 1885, sitting alongside the moderate Opportunist Republicans, opposed both to Georges Clemenceau's Radicals and to the Socialists. He then supported both Jules Ferry and Léon Gambetta.

In 1889, after unsuccessfully contesting Castres, this time under the

banner of Socialism, he returned to his professional duties at Toulouse,

where he took an active interest in municipal affairs, and helped to

found the medical faculty of the University. He also prepared two theses

for his doctorate in philosophy, De primis socialismi germanici lineamentis apud Lutherum, Kant, Fichte et Hegel (1891), and De la réalité du monde sensible.

Jean Jaurès was initially a moderate republican, opposed to both radicalism (such as that of Georges Clemenceau) and socialism. He developed into a socialist during the late 1880s.

In 1892, Jaurès supported the miners of Carmaux when they went on strike over the dismissal of their leader, Jean Baptiste Calvignac. Jaurès' campaigning forced the government to intervene and require Calvignac's reinstatement. The following year, Jaurès was re-elected to the National Assembly as socialist deputy for Tarn, a seat he retained (apart from the four years 1898 to 1902) until his death.

Defeated in the election of 1898 he spent four years without a

legislative seat. His eloquent speeches nonetheless made him a force to

be reckoned with as an intellectual champion of Socialism. He edited La Petite République, and was, along with Emile Zola, one of the most energetic defenders of Alfred Dreyfus (during the Dreyfus Affair that polarized the Right and Left). He approved of the inclusion of Alexandre Millerand, the socialist, in the René Waldeck - Rousseau cabinet, though this led to a split with the more revolutionary section led by Jules Guesde.

In 1902 Jaurès was again returned as deputy for Albi. Jaurès and the independent socialists merged in 1902 with Paul Brousse's "possibilist" (reformist) Federation of the Socialist Workers of France and with Jean Allemane's Revolutionary Socialist Workers Party to form the French Socialist Party, of which Jaurès became the leader. They represented a social democratic stance, opposed to Jules Guesde's revolutionary Socialist Party of France.

During the Combes administration his influence secured the coherence of the Radical - Socialist coalition known as the Bloc des gauches, which enacted the 1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and the State. In 1904, he founded the socialist paper L'Humanité. Following the 1904 Amsterdam Congress of the Second International, the French socialist groups held a Congress at Rouen in March 1905, which resulted in a new consolidation, with the merger of Jaurès's French Socialist Party and Guesde's Socialist Party of France. The new party, headed by Jaurès and Guesde, ceased to co-operate with the Radical groups, and became known as the Parti Socialiste Unifié (PSU, Unified Socialist Party), pledged to advance a collectivist program. All the socialist movements unified the same year in the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO). In the general elections of 1906, Jaurès was again elected for the Tarn.

His ability was now generally recognized, but the strength of the SFIO still had to reckon with the vigorous radicalism of Georges Clemenceau, who was able to appeal to his countrymen (in a notable speech in the spring of 1906) to rally to a Radical program which had no socialist ideas in view, although Clemenceau was sensitive to the conditions of the working class. Clemenceau's image as a strong and practical Radical leader considerably diminished the popularity of the socialists. Jaurès, in addition to his daily journalistic activity, published Les preuves; Affaire Dreyfus (1900); Action socialiste (1899); Etudes socialistes (1902), and, with other collaborators, Histoire socialiste (1901), etc.

Jaurès traveled to Lisbon and Buenos Aires in 1911. He supported, albeit not without criticisms, the teaching of regional languages, such as Occitan, Basque and Breton, commonly known as "patois", thus opposing, in this issue, traditional Republican jacobinism.

Jaurès was a committed anti - militarist who tried to use diplomatic means to prevent what became the First World War. In 1913 he opposed Émile Driant's law, which implemented a three year draft period, and tried to promote understanding between France and Germany. As conflict became imminent, he tried to organize general strikes in France and Germany

in order to force the governments to back down and negotiate. This

proved difficult, however, as many Frenchmen sought revenge (revanche) for their country's defeat in the Franco - Prussian War and the return of the lost Alsace - Lorraine territory.

On 31 July 1914 Jaurès was assassinated in a Parisian café, Le Croissant, 146 rue Montmartre, by Raoul Villain, a 29 year old French nationalist. Jaurès had been due to attend a conference of the International on 9 August, in an attempt to dissuade the belligerents from going ahead with the war. Villain was tried after World War I and acquitted, but was killed by Spanish Republicans in 1936.

Ten years after his death, Jaurès's remains were transferred to the Panthéon.