<Back to Index>

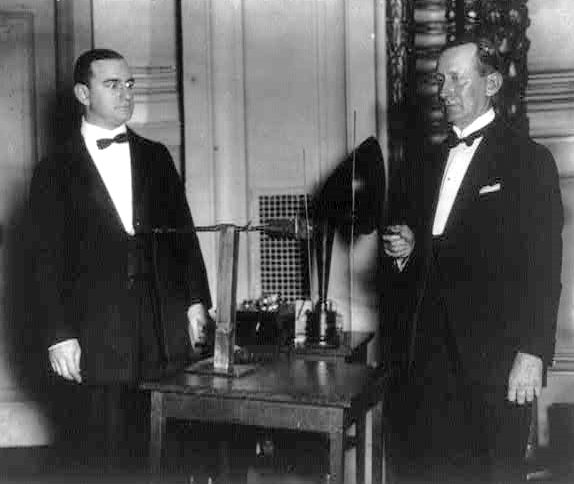

- Inventor and Physicist Guglielmo Marconi, 1874

PAGE SPONSOR

Guglielmo Marconi (25 April 1874 – 20 July 1937) was an Italian inventor, known as the father of long distance radio transmission and for his development of Marconi's law and a radio telegraph system. Marconi is often credited as the inventor of radio, and indeed he shared the 1909 Nobel Prize in Physics with Karl Ferdinand Braun "in recognition of their contributions to the development of wireless telegraphy". Much of Marconi's work in radio transmission was built upon previous experimentation and the commercial exploitation of ideas by others such as Hertz, Maxwell, Faraday, Popov, Lodge, Fessenden, Stone, Bose and Tesla. As an entrepreneur, businessman, and founder of the The Wireless Telegraph & Signal Company in 1897, Marconi succeeded in making a commercial success of radio by innovating and building on the work of previous experimenters and physicists. In 1924, he was ennobled as Marchese Marconi.

Marconi was born in Bologna on April 25, 1874, the second son of Giuseppe Marconi, an Italian landowner, and his Irish wife, Annie Jameson, daughter of Andrew Jameson of Daphne Castle in the County Wexford, Ireland, and granddaughter of John Jameson, founder of whiskey distillers Jameson & Sons. Marconi was educated privately in Bologna in the lab of Augusto Righi, in Florence at the Istituto Cavallero and, later, in Livorno. As a child Marconi did not do well in school. Baptized as a Catholic, he was also a member of the Anglican Church, being married into it; however, he still received a Catholic annulment.

During his early years, Marconi had an interest in science and electricity. One of the scientific developments during this era came from Heinrich Hertz, who, beginning in 1888, demonstrated that one could produce and detect electromagnetic radiation — now generally known as radio waves, at the time more commonly called "Hertzian waves" or "aetheric waves". Hertz's death in 1894 brought published reviews of his earlier discoveries, and a renewed interest on the part of Marconi. He was permitted to briefly study the subject under Augusto Righi, a University of Bologna physicist and neighbor of Marconi who had done research on Hertz's work.

Marconi began to conduct experiments, building much of his own equipment in the attic of his home at the Villa Griffone in Pontecchio, Italy, with the help of his butler Mignani. His goal was to use radio waves to create a practical system of "wireless telegraphy" — i.e., the transmission of telegraph messages without connecting wires as used by the electric telegraph. This was not a new idea — numerous investigators had been exploring wireless telegraph technologies for over 50 years, but none had proven technically and commercially successful. Marconi's system had the following components:

- A relatively simple oscillator, or spark - producing radio transmitter.

- A wire or capacity area placed at a height above the ground;

- A coherer receiver, which was a modification of Edouard Branly's original device, with refinements to increase sensitivity and reliability;

- A telegraph key to operate the transmitter to send short and long pulses, corresponding to the dots - and - dashes of Morse code; and

- A telegraph register, activated by the coherer, which recorded the received Morse code dots and dashes onto a roll of paper tape.

Similar configurations using spark - gap transmitters plus coherer - receivers had been tried by others, but many were unable to achieve transmission ranges of more than a few hundred meters.

Marconi, just twenty years old, began his first experiments working on his own with the help of his butler Mignani. In the summer of 1894, he built a storm alarm made up of a battery, a coherer, and an electric bell, which went off if there was lightning. Soon after he was able to make a bell ring on the other side of the room by pushing a telegraphic button on a bench.

One night in December, Guglielmo woke his mother up and invited her into his secret workshop and showed her the experiment he had created. The next day he also showed his father, who, when he was certain there were no wires, gave his son all of the money he had in his wallet so Guglielmo could buy more materials. In the summer of 1895 he moved his experimentation outdoors. After increasing the length of the transmitter and receiver antennas, and arranging them vertically, and positioning the antenna so that it touched the ground, the range increased significantly. Soon he was able to transmit signals over a hill, a distance of approximately 2.4 kilometers (1.5 mi). By this point he concluded that with additional funding and research, a device could become capable of spanning greater distances and would prove valuable both commercially and militarily.

Marconi wrote to the ministry of Post and Telegraphs, which at the time was under the direction of the honorable Pietro Lacava, explaining his wireless telegraph machine and asking for funding. He never received a response to his letter which was eventually dismissed by the minister who wrote "to the Longara" on the document, referring to the insane asylum on via della Lungara in Rome. In 1896, Marconi spoke with his family friend Carlo Gardini, the United States consulate in Bologna, about leaving Italy to go to England. Gardini wrote a letter to the Ambassador of Italy in London, Annibale Ferrero, explaining who Marconi was and about this extraordinary discoveries. In his response, ambassador Ferrero advised them not to reveal the results until after they had obtained the copyrights. He also encouraged him to come to England where he believed it would be easier to find the necessary funds to convert the findings from Marconi's experiment into a practical use. Finding little interest in his work in Italy, in early 1896 at the age of 21, Marconi traveled to London, accompanied by his mother, to seek support for his work; Marconi spoke fluent English in addition to Italian. While there, he gained the interest and support of William Preece, the Chief Electrical Engineer of the British Post Office. The apparatus that Marconi possessed at that time was similar to that of one in 1882 by A.E. Dolbear, of Tufts College, which used a spark coil generator and a carbon granular rectifier for reception. A plaque on the outside of BT Centre commemorates Marconi's first public transmission of wireless signals from that site. A series of demonstrations for the British government followed — by March 1897, Marconi had transmitted Morse code signals over a distance of about 6 kilometers (3.7 mi) across the Salisbury Plain. On 13 May 1897, Marconi sent the first ever wireless communication over open sea. It transversed the Bristol Channel from Lavernock Point (South Wales) to Flat Holm Island, a distance of 6 kilometers (3.7 mi). The message read "Are you ready". The receiving equipment was almost immediately relocated to Brean Down Fort on the Somerset coast, stretching the range to 16 kilometres (9.9 mi).

Impressed by these and other demonstrations, Preece introduced Marconi's ongoing work to the general public at two important London lectures: "Telegraphy without Wires", at the Toynbee Hall on 11 December 1896; and "Signaling through Space without Wires", given to the Royal Institution on 4 June 1897.

Numerous additional demonstrations followed, and Marconi began to receive international attention. In July 1897, he carried out a series of tests at La Spezia in his home country, for the Italian government. A test for Lloyds between Ballycastle and Rathlin Island, Ireland, was conducted on 6 July 1898. The English channel was crossed on 27 March 1899, from Wimereux, France, to South Foreland Lighthouse, England, and in the autumn of 1899, the first demonstrations in the United States took place, with the reporting of the America's Cup international yacht races at New York.

Marconi sailed to the United States at the invitation of the New York Herald newspaper to cover the America's Cup races off Sandy Hook, NJ. The transmission was done aboard the SS Ponce, a passenger ship of the Porto Rico Line. Marconi left for England on 8 November 1899 on the American Line's SS St. Paul, and he and his assistants installed wireless equipment aboard during the voyage. On 15 November the St. Paul became the first ocean liner to report her imminent arrival by wireless when Marconi's Needles station contacted her sixty - six nautical miles off the English coast.

Around the turn of the 19th to 20th century, Marconi began investigating

the means to signal completely across the Atlantic, in order to compete

with the transatlantic telegraph cables.

Marconi established a wireless transmitting station at Marconi House,

Rosslare Strand, Co. Wexford in 1901 to act as a link between Poldhu in

Cornwall and Clifden in Co. Galway. He soon made the announcement that

on 12 December 1901, using a 152.4 meter (500 ft) kite - supported antenna

for reception, the message was received at Signal Hill in St John's, Newfoundland (now part of Canada), signals transmitted by the company's new high power station at Poldhu, Cornwall.

The distance between the two points was about 3,500 kilometers

(2,200 mi). Heralded as a great scientific advance, there was — and

continues to be — some skepticism about this claim, partly because the

signals had been heard faintly and sporadically. There was no

independent confirmation of the reported reception, and the

transmissions, consisting of the Morse code letter S sent

repeatedly, were difficult to distinguish from atmospheric noise. (A

detailed technical review of Marconi's early transatlantic work appears

in John S. Belrose's work of 1995.) The Poldhu transmitter was a two stage circuit. The first stage operated at lower voltage and provided the energy for the second stage to spark at a higher voltage. Nikola Tesla,

a rival in transatlantic transmission, stated after being told of

Marconi's reported transmission that "Marconi [... was] using seventeen

of my patents."

Feeling challenged by skeptics, Marconi prepared a better organized and documented test. In February 1902, the SS Philadelphia sailed west from Great Britain with Marconi aboard, carefully recording signals sent daily from the Poldhu station. The test results produced coherer - tape reception up to 2,496 kilometers (1,551 mi), and audio reception up to 3,378 kilometers (2,099 mi). The maximum distances were achieved at night, and these tests were the first to show that for medium wave and long wave transmissions, radio signals travel much farther at night than in the day. During the daytime, signals had only been received up to about 1,125 kilometers (699 mi), less than half of the distance claimed earlier at Newfoundland, where the transmissions had also taken place during the day. Because of this, Marconi had not fully confirmed the Newfoundland claims, although he did prove that radio signals could be sent for hundreds of kilometers, despite some scientists' belief they were essentially limited to line - of - sight distances.

On 17 December 1902, a transmission from the Marconi station in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia, Canada, became the first radio message to cross the Atlantic from North America. In 1901, Marconi built a station near South Wellfleet, Massachusetts, that on January 18, 1903 sent a message of greetings from Theodore Roosevelt, the President of the United States, to King Edward VII of the United Kingdom, marking the first transatlantic radio transmission originating in the United States. This station also was one of the first to receive the distress signals coming from the RMS Titanic. However, consistent transatlantic signalling was difficult to establish.

Marconi began to build high powered stations on both sides of the Atlantic to communicate with ships at sea, in competition with other inventors. In 1904 a commercial service was established to transmit nightly news summaries to subscribing ships, which could incorporate them into their on-board newspapers. A regular transatlantic radio telegraph service was finally begun on 17 October 1907 between Clifden Ireland and Glace Bay, but even after this the company struggled for many years to provide reliable communication.

The two radio operators aboard the Titanic — Jack Phillips and Harold Bride — were not employed by the White Star Line, but by the Marconi International Marine Communication Company. Following the sinking of the ocean liner, survivors were rescued by the RMS Carpathia of the Cunard Line. Also employed by the Marconi Company was David Sarnoff, the only person to receive the names of survivors immediately after the disaster via wireless technology. Wireless communications were reportedly maintained for 72 hours between the Carpathia and Sarnoff, but Sarnoff's involvement has been questioned by some modern historians. When the Carpathia docked in New York, Marconi went aboard with a reporter from The New York Times to talk with Bride, the surviving operator. On 18 June 1912, Marconi gave evidence to the Court of Inquiry into the loss of the Titanic regarding the marine telegraphy's functions and the procedures for emergencies at sea. Britain's postmaster general summed up, referring to the Titanic disaster, "Those who have been saved, have been saved through one man, Mr. Marconi... and his marvelous invention."

Over the years, the Marconi companies gained a reputation for being

technically conservative, in particular by continuing to use inefficient

spark - transmitter technology, which could only be used for

radiotelegraph operations, long after it was apparent that the future of

radio communication lay with continuous - wave

transmissions, which were more efficient and could be used for audio

transmissions. Somewhat belatedly, the company did begin significant

work with continuous - wave equipment beginning in 1915, after the

introduction of the oscillating vacuum tube (valve). In 1920, employing a

vacuum tube transmitter, the Chelmsford Marconi factory was the location for the first entertainment radio broadcasts in the United Kingdom — one of these featured Dame Nellie Melba. In 1922 regular entertainment broadcasts commenced from the Marconi Research Centre at Writtle.

In 1914 Marconi was made a Senator in the Italian Senate and appointed Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order in the UK. During World War I, Italy joined the Allied side of the conflict, and Marconi was placed in charge of the Italian military's radio service. He attained the rank of lieutenant in the Italian Army and of commander in the Italian Navy. In 1924, he was made a marquess by King Victor Emmanuel III.

Marconi joined the Italian Fascist party in 1923. In 1930, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini appointed him President of the Royal Academy of Italy, which made Marconi a member of the Fascist Grand Council.

Marconi died in Rome in 1937 at age 63 following a series of heart attacks, and Italy held a state funeral

for him. As a tribute, all radio stations throughout the world observed

two minutes of silence. His remains are housed in the Villa Griffone at

Sasso Marconi, Emilia - Romagna, which assumed that name in his honor in 1938.

Marconi had a brother, Alfonso, and a stepbrother, Luigi. On 16 March 1905, Marconi married the Hon. Beatrice O'Brien (1882 – 1976), a daughter of Edward Donough O'Brien, 14th Baron Inchiquin. They had three daughters, Degna (1908 – 1998), Gioia (1916 – 1996), and Lucia (born and died 1906), and a son, Giulio, 2nd Marchese Marconi (1910 – 1971). The Marconis divorced in 1924, and, at Marconi's request, the marriage was annulled on 27 April 1927, so he could remarry. Beatrice Marconi married her second husband, Liborio Marignoli, Marchese di Montecorona, on 3 March 1924 and had a daughter, Flaminia.

On 12 June 1927 (religious 15 June), Marconi married Maria Cristina Bezzi - Scali (1900 - 1994), only daughter of Francesco, Count Bezzi - Scali. Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini was Marconi's best man at the wedding. They had one daughter, Maria Elettra Elena Anna (born 1930), who married Prince Carlo Giovannelli (born 1942) in 1966; they later divorced.

For unexplained reasons, Marconi left his entire fortune to his second wife and their only child, and nothing to the children of his first marriage.

Later in life, Marconi was an active Italian Fascist and an apologist for their ideology and actions such as the attack by Italian forces in Ethiopia.

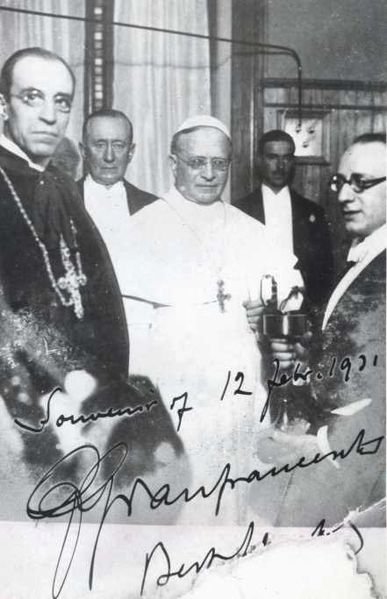

Marconi wanted to personally introduce in 1931 the first radio broadcast of a Pope, Pius XI,

announcing at the microphone: "With the help of God, who places so many

mysterious forces of nature at man's disposal, I have been able to

prepare this instrument which will give to the faithful of the entire

world the joy of listening to the voice of the Holy Father".