<Back to Index>

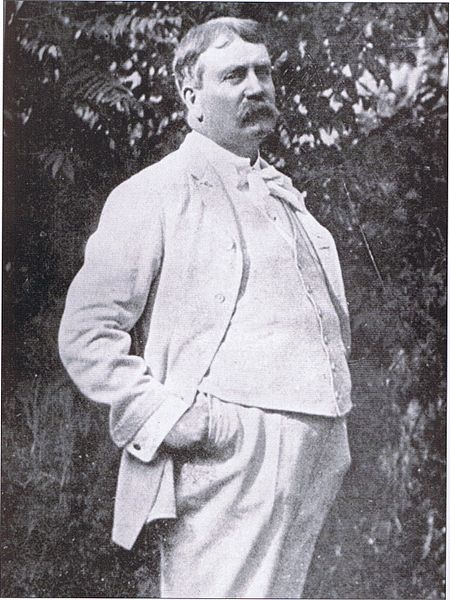

- Painter and Inventor William Harbutt, 1844

- Architect and Urban Planner Daniel Hudson Burnham, 1846

PAGE SPONSOR

William Harbutt (13 February 1844 - 1 June 1921) was a painter and the inventor of Plasticine.

Born in North Shields, England, Harbutt studied at the National Art Training School in London, and eventually became an associate of the Royal College of Art. He was headmaster of the Bath School of Art and Design from 1874 to 1877, and then opened his own art school at The Paragon Art Studio, 15 Bladud Buildings, Bath, with his wife Elizabeth (Bessie), a well known miniature portrait artist who exhibited works at the Royal Academy of Art and the Chicago World's Fair, and in 1887 was commissioned by Queen Victoria to produce portraits of herself and her late husband Prince Albert.

Harbutt invented Plasticine around 1897 as a non - drying modelling clay for use by his students. At the time he was living in Hartley House, Alfred Street, Bath; later moving to The Grange, High Street, Bathampton. In 1899 Harbutt was awarded a trade mark, and in 1900 a factory was set up at nearby Bathampton to manufacture the product for commercial sale. Harbutt traveled widely to promote the product, and his theories about the teaching of art by allowing children free expression. He died of pneumonia while on a trip to New York in 1921.

Harbutt was also a councilor on Bath rural district council and Bathampton parish council. He and Bessie had seven children, six of whom survived infancy and worked in the family business. The Harbutt company, owned and run by Harbutt's descendants, continued to manufacture Plasticine in Bathampton until 1983.

The Paradise in Plasticine garden, a creation of

journalist and presenter James May displayed at the 2009

Chelsea Flower Show included a bust of Harbutt sculpted by

Jane McAdam Freud.

Daniel Hudson Burnham, FAIA (September 4, 1846 – June 1, 1912) was an American architect and urban planner. He was the Director of Works for the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. He took a leading role in the creation of master plans for the development of a number of cities, including Chicago and downtown Washington D.C. He also designed several famous buildings, including the Flatiron Building in New York City and Union Station in Washington D.C.

Burnham was born in Henderson, New York, and raised in Chicago, Illinois. His parents brought him up under the teachings of the Swedenborgian Church of New Jerusalem, which ingrained in him the strong belief that man should strive to be of service to others. After failing admissions tests for both Harvard and Yale, and an unsuccessful stint at politics, Burnham apprenticed as a draftsman under William LeBaron Jenney. At age 26, Burnham moved on to the Chicago offices of Carter, Drake and Wight, where he met future business partner John Wellborn Root (1850 – 1891).

Burnham and Root were the architects of one of the first American skyscrapers: the Masonic Temple Building in Chicago. Measuring 21 stories and 302 feet, the Temple held claims as the tallest building of its time, but was torn down in 1939. Under the design influence of Root, the firm had produced modern buildings as part of the Chicago School. Following Root’s premature death from pneumonia in 1891, the firm became known as D.H. Burnham & Company.

Burnham and Root had accepted responsibility to oversee design and construction of the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago’s then desolate Jackson Park on the south lakefront. The largest world's fair to that date (1893), it celebrated the 400 year anniversary of Christopher Columbus' famous voyage. After Root's sudden and unexpected death, a team of distinguished American architects and landscape architects, including Burnham, Frederick Law Olmsted, Charles McKim and Louis Sullivan, radically changed Root's modern and colorful style to a Classical Revival style. Under Burnham's direction, the construction of the Fair overcame huge financial and logistical hurdles, including a worldwide financial panic and an extremely tight time frame, to open on time.

Considered the first example of a comprehensive planning

document in the nation, the fairground was complete with

grand boulevards, classical building facades, and lush

gardens. Often called the "White City", it popularized

neoclassical architecture in a monumental and rational

Beaux - Arts plan. The remaining population of architects

in the U.S. were soon asked by clients to incorporate

similar elements into their designs.

Initiated in 1906 and published in 1909, Burnham and his co-author Edward H. Bennett prepared "The Plan of Chicago", which laid out plans for the future of the city. It was the first comprehensive plan for the controlled growth of an American city, and an outgrowth of the City Beautiful movement. The plan included ambitious proposals for the lakefront and river and declared that every citizen should be within walking distance of a park. Sponsored by the Commercial Club of Chicago, Burnham donated his services in hopes of furthering his own cause.

Plans and conceptual designs of the south lakefront from the Exposition came in handy, as he envisioned Chicago being a "Paris on the Prairie". French inspired public works constructions, fountains, and boulevards radiating from a central, domed municipal palace became Chicago's new backdrop. Though only parts of the plan were actually implemented, it set the standard for urban design, anticipating future need to control unexpected urban growth, and continued to influence the development of Chicago long after Burnham's death.

City planning projects did not stop at Chicago though. Burnham contributed to plans for cities such as Cleveland (the Group Plan), San Francisco and Manila and Baguio in the Philippines, details of which appear in "The Chicago Plan" publication of 1909. His plans for the redesign of San Francisco were delivered to City Hall on April 17, 1906, the day before the 1906 earthquake. In the haste to rebuild the city, the plans were ultimately ignored. The Plan for Manila never fully materialized, except for a shore road, which became Dewey boulevard, now known as Roxas boulevard and various neo - classical government buildings around Luneta Park, which very much resembles a mini version of Washington D.C.

In Washington, D.C., Burnham did much to shape the McMillan Plan, which led to the completion of the overall design of the National Mall. Going well beyond Pierre L'Enfant's original vision for the city, the plan provided for the extension of the Mall beyond the Washington Monument to a new Lincoln Memorial and a "pantheon" that eventually materialized as the Jefferson Memorial. Inter alia, this involved significant reclamation of land from swamp and the Potomac River, and the relocation of an existing railroad station on the site, which was replaced by Burnham's own design for Union Station.

Much

of his career work modeled the classical style of Greece

and Rome. In his 1924 autobiography, Louis Sullivan, one

of the leading architects from the Chicago School but one

who had enjoyed difficult relations with Burnham over an

extended period, criticized Burnham for what Sullivan

viewed as his lack of original expression and dependence

on Classicism. Sullivan went on to claim that "the damage

wrought by the World's Fair will last for half a century

from its date, if not longer" — a sentiment edged with

bitterness, as corporate America of the early twentieth

century had demonstrated a strong preference for Burnham's

architectural style over Sullivan's.

Burnham was quoted after his death as saying, "Make no little plans. They have no magic to stir men's blood and probably will not themselves be realized." (Moore 1921) This slogan has been taken to capture the essence of Burnham's spirit, although there is no documented evidence that he actually used those words.

A man of influence, Burnham was considered the preeminent architect in America at the turn of the twentieth century. He held many positions during his lifetime, including the presidency of the American Institute of Architects. Other notable architects began their careers under his aegis, such as Joseph W. McCarthy. In 1912, when he died in Heidelberg, Germany, D.H. Burnham and Co. was the world's largest architectural firm. Even legendary architect Frank Lloyd Wright, although strongly critical of Burnham's Beaux Arts European influences still admired him as a man, eulogized: "(Burnham) made masterful use of the methods and men of his time... (as) an enthusiastic promoter of great construction enterprises... his powerful personality was supreme." His firm continues its work today under the name Graham, Anderson, Probst & White, which it adopted in 1917.

Tributes to Burnham include Burnham Park and Daniel Burnham Court in Chicago, Burnham Park in Baguio City in the Philippines, Burnham Alley in San Francisco (formerly Hemlock Street between Van Ness Avenue and Franklin Street), the annual Daniel Burnham Award for a Comprehensive Plan (run by the American Planning Association), and the Burnham Memorial Competition held in 2009 to create a memorial to Burnham and his Plan of Chicago. Collections of Burnham's personal and professional papers, photographs, and other archival materials are held by the Ryerson & Burnham Libraries at the Art Institute of Chicago.