<Back to Index>

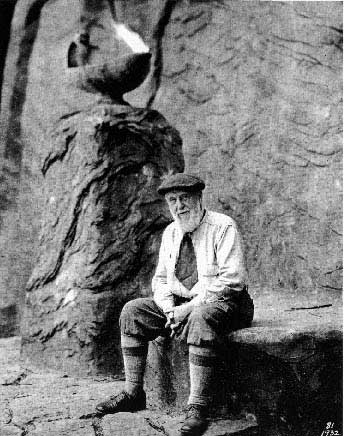

- Architect Bernard Ralph Maybeck, 1862

- Archeologist and Designer Henry Chapman Mercer, 1856

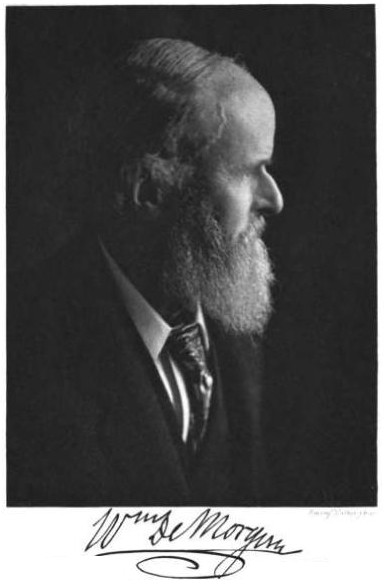

- Potter and Tile Designer William Frend De Morgan, 1839

PAGE SPONSOR

Bernard Ralph Maybeck (February 7, 1862 – October 3, 1957) was an American architect in the Arts and Crafts Movement of the early 20th century. He was a professor at University of California, Berkeley. Many of his major buildings were in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Maybeck was born in New York City, the son of a German immigrant and studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, France. He moved to Berkeley, California, in 1892. He became a professor of engineering drawing at University of California, Berkeley, and acted as a mentor for an entire generation of other California architects, including Julia Morgan and William Wurster. In 1951, he was awarded the Gold Medal of the American Institute of Architects.

Maybeck was equally comfortable producing work in the Mission style and Mission Revival style, Gothic revival, Arts and Crafts style, and Beaux - Arts classicism, believing that each architectural problem required development of an entirely new solution. Maybeck's contributions include the Mission Style California Building at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago and the first Mission Style chair designed for the San Francisco Swedenborgian Church.

Many of his buildings still stand in his long time home city of Berkeley. The 1910 First Church of Christ, Scientist is designated a National Historic Landmark and is considered one of Maybeck's finest works. It is a strange confection of medieval European, Japanese, Nordic, Celtic and shingle style architecture, but the effect is magical. The church has an ongoing program of repairs that have kept the building in good shape.

In 1914, Maybeck oversaw the building of the Maybeck Recital Hall in Berkeley, California. Maybeck also designed the domed Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco as part of the 1915 Panama - Pacific International Exposition, and he carried out his vision of the lumberman's lodge, House of Hoo Hoo, made of little more than rough barked tree trunks arranged in delicate harmony. The Palace of Fine Arts was seen as the embodiment of Maybeck's elaboration of how Roman architecture could fit within a California context. Maybeck said that the popular success of the Palace was due to the absence of a roof connecting the rotunda to the art gallery building, along with the absence of windows in the gallery walls and the presence near the rotunda of trees, flowers and a water feature.

One of Maybeck's most interesting office buildings is the home of the Family Service Agency of San Francisco, offices at 1010 Gough Street. This building, constructed in 1928, is on the city's Historic Building Register and still serves as Family Service headquarters. Some of his larger residential projects, most notably a few in the hills of Berkeley, California (esp. La Loma Park), have been compared to the ultimate bungalows of the architects Greene and Greene.

He also developed a comprehensive town plan for the company town of Brookings, Oregon, a clubhouse at the Bohemian Grove, and many of the buildings on the campus of Principia College in Elsah, Illinois.

A number of his works are listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.

A lifetime fascination with drama and the theater can be seen in much of Maybeck's work. In his spare time, he was known to create costumes, and also designed sets for the amateur productions at Berkeley's Hillside Club.

Bernard Maybeck died in 1959 and is buried in the Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland, California.

Henry Chapman Mercer (born June 24, 1856, Doylestown, Pennsylvania – died March 2, 1930, Doylestown) was an American archeologist, artifact collector, tile maker and designer of three distinctive poured concrete structures: Fonthill, his home, the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works, and the Mercer Museum.

Henry Mercer was born in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, on June 24, 1856. Mercer first traveled to Europe in 1870. He attended Harvard University between 1875 and 1879, obtaining a liberal arts degree. Mercer went on to study law at University of Pennsylvania Law School between 1880 and 1881, and he read law with the firm of Freedley and Hollingsworth. The same year he began studying on the University of Pennsylvania, he became a founding member of the Bucks County Historical Society.

Mercer, however, never practiced law. Mercer was admitted to the Philadelphia County Bar on November 9, 1881, but departed for Europe the same month. From 1881 to 1889, Mercer extensively traveled through France and Germany.

The University of Pennsylvania Museum appointed Mercer as the Curator of American and Prehistoric Archeology in the early 1890s. Leaving his position with the Museum in the late 1890s, Mercer devoted himself to finding old American artifacts and learning about German pottery. Mercer believed that American society was being destroyed by industrialism, which inspired his search for American artifacts. Mercer founded Moravian Pottery and Tile Works in 1898 after apprenticing himself to a Pennsylvania German potter. Mercer was also influenced by the American Arts and Crafts Movement.

Mercer is well known for his research and books about ancient tool making, his ceramic tile creations, and his engineering and architecture. He wrote extensively on his interests, which included archeology, early tool making, German stove plates and ceramics. He assembled the collection of early American tools now housed in the Mercer Museum. Mercer's tiles are used in the floor of the Pennsylvania State Capitol Building in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania and in many other noteworthy buildings and houses. In the Pennsylvania State Capitol, Mercer created a series of mosaic images for the floor of the building. The series of four hundred mosaics trace the history of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania from prehistoric times. The Pennsylvania State Capitol is the largest single collection of Mercer's tiles. Other collections of tiles by Mercer can be found at Rockefeller's New York estate, Grauman's Chinese Theater, the casino at Monte Carlo, and the St. Louis Public Library.

The Bucks County Historical Society now owns Fonthill, which is open to the public, and the Mercer Museum. The Moravian Pottery and Tile Works is owned and operated by the Bucks County Department of Parks & Recreation. These three buildings make up "the Mercer Mile". All three buildings were designed and constructed by Henry Mercer in the early part of the 20th century.

Henry Ford stated that the Mercer museum was the only museum worth visiting in the United States, and the Mercer Museum was apparently Henry Ford's inspiration for his own museum, The Henry Ford, located in Dearborn, Michigan. The Mercer Museum houses over forty thousand artifacts from early American society.

Mercer died on March 2, 1930 at Fonthill, the house he designed and constructed from reinforced concrete in 1908 - 1912.

William Frend De Morgan (16 November 1839 – 15 January 1917) was an English potter and tile designer. A lifelong friend of William Morris, he designed tiles, stained glass and furniture for Morris & Co. from 1863 to 1872. His tiles are often based on medieval designs or Persian patterns, and he experimented with innovative glazes and firing techniques. Galleons and fish were popular motifs, as were "fantastical" birds and other animals. Many of De Morgan's tile designs were planned to create intricate patterns when several tiles were laid together.

Born in Gower Street, London, the son of the distinguished mathematician Augustus De Morgan and his highly educated wife, De Morgan was always supported in his desire to become an artist. At the age of twenty he entered the Royal Academy schools, but he was swiftly disillusioned with the establishment; then he met Morris, and through him the Pre - Raphaelite circle. Soon De Morgan began experimenting with stained glass, ventured into pottery in 1863, and by 1872 had shifted his interest wholly to ceramics.

In 1872, De Morgan set up a pottery works in Chelsea where he stayed through 1881 — his most fruitful decade as an art potter. The arts and crafts ideology he was exposed to through his friendship with Morris and his own insistent curiosity, led De Morgan to begin to explore every technical aspect of his craft. His early efforts at making his own tiles during his Chelsea Period were of variable technical quality - often amateurish with firing defects and irregularities. In his early years De Morgan made extensive use of blank commercial tiles. Biscuit tiles of red clay were obtained from the Architectural Pottery Co. in Poole and these are hard and very durable. Dust pressed tiles of white earthenware were bought from Wedgwood, Mintons and other manufacturers but De Morgan believed these would not stand frost. He continued to use blank commercial dust - pressed tiles which were decorated in red luster into his Fulham Period (1888 - 1907). However he developed a high quality biscuit tile of his own, which he admired for its irregularities and better resistance to moisture. His inventive streak led him to spend hours designing a new duplex bicycle gear and also lured him into complex studies of the chemistry of glazes, methods of firing and pattern transfer.

De Morgan's decoration of pottery included chargers, rice dishes and vases. Some of these were made in his works but many were bought as biscuit ware from Wedgwood and others and decorated by De Morgan's workers. Some were signed by his decorators including Charles Passenger, Fred Passenger, Joe Juster and Miss Babb.

De Morgan was particularly drawn to Eastern tiles. Around 1873 – 1874, he made a striking breakthrough by rediscovering the technique of luster ware (characterized by a reflective, metallic surface) found in Hispano - Moresque pottery and Italian maiolica. Nor was his interest in the East limited to glazing techniques, but it permeated his notions of design and color, as well. As early as 1875, he began to work in earnest with a "Persian" palette: dark blue, turquoise, manganese purple, green, Indian red, and lemon yellow, Study of the motifs of what he referred to as "Persian" ware (and what we know today as fifteenth - and - sixteenth century İznik ware), profoundly influenced his unmistakable style, in which fantastic creatures entwined with rhythmic geometric motifs float under luminous glazes.

The pottery works was always beset by financial problems, despite repeated cash injections from his wife, the pre - Raphaelite painter Evelyn Pickering De Morgan, and a partnership with the architect Halsey Ricardo. This partnership was associated with a move for the factory from Merton Abbey to Fulham in 1888. During the Fulham period De Morgan mastered many of the technical aspects of his work that had previously been elusive, including complex lusters and deep, intense underglaze painting that did not run during firing. However, this did not guarantee financial success, and in 1907 William De Morgan left the pottery, which continued under the Passenger brothers, the leading painters at the works. "All my life I have been trying to make beautiful things," he said at the time, "and now that I can make them nobody wants them."

William De Morgan turned his hand to writing novels, and became better known than he ever had been for his pottery. His first novel, Joseph Vance, was published in 1906, and was an instant sensation in the United States as well as the United Kingdom. This was followed by An Affair of Dishonour, Alice - for - Short, and It Never Can Happen Again. The genre has been described as 'Victorian and suburban'.

William De Morgan died in London in 1917, of trench fever, and was buried in Brookwood Cemetery. Recollections of William De Morgan praise him both for his personal warmth and the indomitable energy with which he pursued his kaleidoscopic career as designer, potter, inventor and novelist.

Collections of De Morgan's work exist in many museums, including the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the William Morris Gallery in London, a substantial and representative collection in Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, and a small but well chosen collection along with much other pottery at Norwich. His dragon charger is in the Dunedin Public Art Gallery in New Zealand. The National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa has a very good collection of William De Morgan's work given by Ruth Amelia Jackson in 1997 but much of it is kept in store. De Morgan's work is also present in many major collections with decorative art including the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada, the Musee D'Orsay, Paris, Manchester Art Gallery and the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

A number of properties in the UK open to the public have tiles and pottery on display or incorporated in the building's decoration. These include Wightwick Manor (the National Trust, Wolverhampton), Standen (the National Trust,East Grinstead), Blackwell (Lakeland Arts Trust, Windermere) and Leighton House (London Borough of Kensington).