<Back to Index>

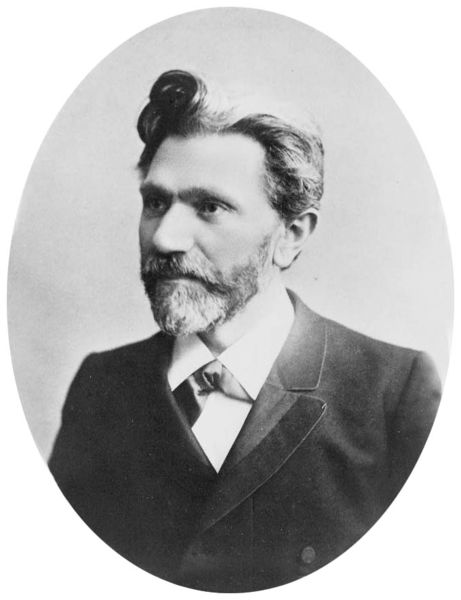

- Founder of the SPD Ferdinand August Bebel, 1840

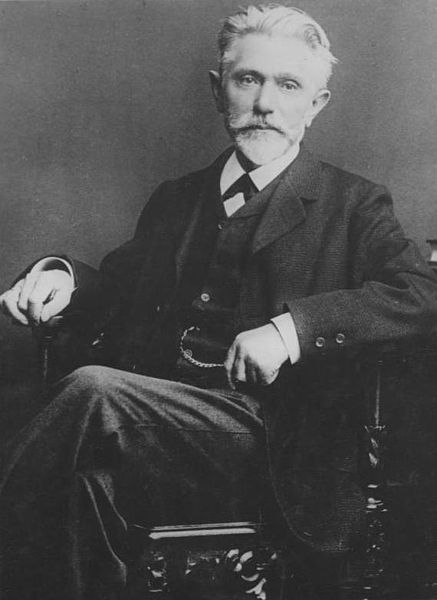

- Political Theorist Eduard Bernstein, 1850

PAGE SPONSOR

Ferdinand August Bebel (22 February 1840, Deutz, Rhenish Prussia – 13 August 1913, Passugg, Graubünden) was a German Marxist politician, writer and orator. He is best remembered as one of the founders of the Social Democratic Party of Germany.

Ferdinand August Bebel, known to all by his middle name, was born February 22, 1840, in Deutz, Germany, now a part of Cologne. He was the son of a Prussian non - commissioned officer in the Prussian infantry, initially from Ostrowo in the Province of Posen, and was born in military barracks.

As a young man, Bebel apprenticed as a carpenter and joiner in Leipzig. Like most German workmen at that time, he traveled extensively in search of work and he thereby obtained a first hand knowledge of the difficulties facing the working people of the day.

At Salzburg, where he lived for some time, he joined a Roman Catholic workmen's club. When in Tyrol in 1859 he volunteered for service in the war against Italy, but was rejected; and in his own country he was rejected likewise as physically unfit for the army.

In 1860 he settled in Leipzig as a master turner, making horn buttons. He joined various labor organizations. Although initially an opponent of socialism, Bebel gradually was won over to socialist ideas through reading the pamphlets of Ferdinand Lassalle, which popularized the ideas of Karl Marx. In 1865 he came under the influence of Wilhelm Liebknecht and was thereafter committed fully to the socialist cause.

Following the death of Lassalle, Bebel was among the group of Socialists that refused to follow new party leader Johann Baptist von Schweitzer at the Eisenach Conference of 1867, an action which gave rise to the name "Eisenachers" for this Marxist faction. Together with Liebknecht, he founded the Sächsische Volkspartei ("Saxon People's Party"). Bebel was also President of the Union of German Workers' Associations from 1867 and a member of the First International.

Bebel was elected to the North German Reichstag as a member from Saxony in that same year.

In 1869 he helped found the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany (SDAP), which later merged with another organization in 1875 to form the Socialist Workers' Party of Germany (SAPD), which in turn became the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) in 1890.

Bebel's great organizing talent and oratorical power quickly made him one of the leaders of the socialists and their chief spokesman in parliament. He remained a member of the North German Parliament, and later of its counterpart for the German Empire, the Reichstag, until his death, except for the interval of 1881 - 83. He represented successively the districts of Glauchau - Meerane, Dresden, Strassburg, and Hamburg. Later in his life, he acted as chairman of the SPD. Representing as he did Marxian principles, he was bitterly opposed by certain factions of his party.

In 1870 he spoke in parliament against the continuance of the war with France. Bebel and Liebknecht were the only members who did not vote the extraordinary subsidy required for the war with France. Bebel was the only socialist who was elected to the Reichstag in 1871, and he used his position to protest against the annexation of Alsace and Lorraine and to express his full sympathy with the Paris Commune. German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck afterwards said that this speech of Bebel's was a “ray of light” showing him that socialism was an enemy to be fought against and crushed. Falsely accused of being in league with the French and part of a conspiracy to free French prisoners of war held in Germany and to lead them in an attack from the rear, Bebel and Liebknecht were arrested for high treason, but no prosecution was possible for lack of evidence.

Not wanting to release such important opponents of the war effort, old charges of preaching dangerous doctrines and plotting against the state were levied against Bebel and Liebknecht in 1872. The pair were convicted and sentenced to two years in Festungshaft (imprisonment in a fortress), which was spent at the famous Königstein Fortress. For insulting the German emperor, Bebel was additionally sentenced to nine months' ordinary imprisonment. This incarceration served to increase Bebel's prestige among his party associates and the sympathetic public at large.

In 1874 Bebel took a partner and founded a small button factory, for which he acted as salesman, but in 1889 he gave up his business to devote himself wholly to politics. In 1868 he became connected with the staff of the Volksstaat ("The People's State") at Leipzig, and in 1891 with that of the Vorwärts ("Forward") at Berlin.

After his release from prison, he helped to organize, at the congress of Gotha, the united party of Social Democrats, which had been formed during his imprisonment. After the passing of the Socialist Law he continued to show great activity in the debates of the Reichstag, and was also elected a member of the Saxon parliament; when the state of siege was proclaimed in Leipzig he was expelled from the city, and in 1886 condemned to nine months' imprisonment for taking part in a secret society.

In party meetings of 1890 and 1891 Bebel's policies were severely attacked, first by the extremists, the “young” Socialists from Berlin, who wished to abandon parliamentary action; against these Bebel won a complete victory. On the other side he was involved in a quarrel with Volmar and his school, who desired to put aside from immediate consideration the complete attainment of the socialist ideal, and proposed that the party should aim at bringing about, not a complete overthrow of society, but a gradual amelioration. This conflict of tendencies continued, and Bebel came to be regarded as the chief exponent of the traditional views of the orthodox Marxist party. Though a strong opponent of militarism, he publicly stated that foreign nations attacking Germany must not expect the help or the neutrality of the Social Democrats.

Bebel particularly distinguished himself by his denunciation of the maltreatment of soldiers by officers and still more frequently by non - commissioned officers. His efforts in this matter had received great encouragement when Albert of Saxony issued an edict dealing with the maltreatment of soldiers in the Saxon contingent, thus cutting the ground from under the feet of the Imperial Government, which had persistently attempted to deny or to explain away the cases put forward by Bebel.

Bebel is also famed for his outrage at the news of a German conducted policy of extermination towards indigenous people in her South - West African colony, the Herero nation in particular. He and the German Social Democratic Party thus voted against the colonial expenditure as the only party in the Reichstag, and in a speech in March 1904 Bebel classified the policy in German West Africa as ‘not only barbaric, but bestial.’ This caused some sections of the contemporary German press to scathingly classify Bebel as 'Der hereroische Bebel'. Bebel was not deterred, he later followed this up with strongly worded warnings against the rising tide of theories of racial hierarchy and racial purity, causing the general election to the German Reichstag in 1907 to go over in history as the ‘Hottentot Election.’

Bebel's book, Women and Socialism was translated into English by Daniel DeLeon of the Socialist Labor Party of America as Woman under Socialism. It figured prominently in the Connolly - DeLeon controversy after James Connolly, then a member of the SLP, denounced it as a "quasi - prurient" book that would repel potential recruits to the socialist movement. The book contained an attack on the institution of marriage which identified Bebel with the most extreme forms of socialism.

August Bebel died August 13, 1913 of a heart attack during a visit to a sanatorium in Passugg, Switzerland. He was 73 years old at the time of his death. His body was buried in Zürich.

At the time of his death Bebel was eulogized by Russian Marxist leader V.I. Lenin as a "model workers' leader," who had proven himself able to "break his own road" from being an ordinary worker into becoming a political leader in the struggle for a "better social system."

The well known saying "Anti - Semitism is the socialism of fools" ("Der Antisemitismus ist der Sozialismus der dummen Kerle") is frequently attributed to Bebel, but probably originated with the Austrian democrat Ferdinand Kronawetter; it was in general use among German Social Democrats by the 1890s.

Bebel, along with Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and Ferdinand Lassalle, was among the socialist icons included in bas relief portraits on the facade of the The Forward building, erected in 1912 as the headquarters of the New York Yiddish language socialist newspaper.

Eduard Bernstein (6 January 1850 – 18 December 1932) was a German social democratic political theorist and politician, a member of the SPD, and the founder of evolutionary socialism and revisionism.

Bernstein was born in Schöneberg (now part of Berlin) to Jewish parents, although they did not practice religion. His father was a locomotive driver. From 1866 to 1878, after leaving school, he was employed in banks as a banker's clerk. His political career began in 1872, when he joined the Eisenach (named after the German town Eisenach) wing of the German socialist movement, a socialist party with Marxist tendencies formally known as Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei Eisenacher Programms and soon became prominent as an activist. Bernstein's party contested two elections against a rival socialist party, the Lassalleans (Ferdinand Lassalle's Allgemeiner Deutscher Arbeiterverein), but in both elections neither party was able to win a significant majority of the left wing vote. Consequently, together with August Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknecht, Bernstein prepared the Einigungsparteitag ("unification party congress") with the Lassalleans in Gotha in 1875. Karl Marx's famous Critique of the Gotha Program criticized what he saw as a Lassallean victory over the Eisenachers whom he favored; interestingly, Bernstein later noted that it was Liebknecht, considered by many to be the strongest Marxist advocate within the Eisenacher faction, who proposed the inclusion of many of the ideas which so thoroughly irritated Marx.

In the Reichstag elections of 1877, the German Social Democratic Party gained 493,000 votes. However, two assassination attempts on the Kaiser in the following year provided Bismarck with a pretext for introducing a law banning all socialist organizations, assemblies and publications. There had been no Social Democratic involvement in either assassination attempt, but the popular reaction against "enemies of the Reich" induced a compliant Reichstag to pass Bismarck's "Socialist Law."

Otto von Bismarck's strict anti - Socialist legislation was passed on 12 October 1878. For nearly all practical purposes, the Social Democratic Party was outlawed and, throughout Germany, it was actively suppressed. However, it was still possible for Social Democrats to stand as individuals for election to the Reichstag, and this they did. Indeed, despite the severe persecution to which it was subjected, the party actually increased its electoral support, gaining 550,000 votes in 1884 and 763,000 in 1887.

The vehemence of Bernstein's opposition to the government of Bismarck made it desirable for him to leave Germany. Shortly before the "Socialist Law" came into effect, he went into exile in Zurich, accepting a position as private secretary for social democratic patron Karl Höchberg, a wealthy supporter of Social Democracy. A warrant subsequently issued for his arrest ruled out any possibility of his returning to Germany, and he was to remain in exile for more than twenty years. In 1888, Bismarck convinced the Swiss government to expel a number of key members of the German social democratic movement from its country, and so Bernstein moved to London, where he had close contacts with Friedrich Engels and Karl Kautsky. It was shortly after his arrival in Switzerland that he began to think of himself as a Marxist. In 1880, he accompanied Bebel to London in order to clear up a misunderstanding over his involvement in an article published by Höchberg and denounced by Marx and Engels as being "chock - full of bourgeois and petty bourgeois ideas." The trip was a success. Engels in particular was impressed by Bernstein's zeal and the soundness of his ideas.

Back in Zurich, Bernstein became increasingly active in working for Der Sozialdemokrat ("Social Democrat"), and later succeeded Georg von Vollmar as the paper's editor, a post he was to hold for the next ten years. It was during these years between 1880 and 1890 that Bernstein established his reputation as a leading party theoretician and a Marxist of impeccable orthodoxy. In this he was helped by the close personal and professional relationship he established with Engels. This relationship owed much to the fact that he shared Engels's strategic vision and accepted most of the particular policies which, in Engels's view, that vision entailed. In 1887, the German government persuaded the Swiss authorities to close down Der Sozialdemokrat. Bernstein moved to London where he resumed publication from premises in Kentish Town. His relationship with Engels soon blossomed into friendship. He also made contact with various English socialist organizations, notably the Fabian Society and Hyndman's Social Democratic Federation. Indeed, in later years, his opponents routinely claimed that his "revisionism" was due to his having come to see the world "through English spectacles." It is, of course, impossible to determine how far the charge was justified. Bernstein himself denied it.

In 1891, he was one of the authors of the Erfurt Program, and from 1896 to 1898, he released a series of articles entitled Probleme des Sozialismus ("Problems of Socialism") that led to the revisionism debate in the SPD. He also wrote a book titled Die Voraussetzungen des Sozialismus und die Aufgaben der Sozialdemokratie ("The Prerequisites for Socialism and the Tasks of Social Democracy") in 1899. The book was in sharp contrast to the positions of August Bebel, Karl Kautsky and Wilhelm Liebknecht. Rosa Luxemburg's 1900 essay Reform or Revolution? was also a polemic against Bernstein's position. In 1900, Berstein published Zur Geschichte und Theorie des Sozialismus ("The history and theory of socialism," 1900).

In 1901, he returned to Germany, following the lifting of a ban that had kept him from entering the country. He became an editor of Vorwärts that year, and a member of the Reichstag from 1902 to 1918. He voted against the armament tabling in 1913, together with the SPD fraction's left wing. Although he had voted for war credits in August 1914, from July 1915 he opposed World War I and in 1917 he was among the founders of the USPD, which united anti - war socialists (including reformists like Bernstein, "centrists" like Kautsky and revolutionary Marxists like Karl Liebknecht). He was a member of the USDP until 1919, when he rejoined the SPD. From 1920 to 1928 Bernstein was again a member of the Reichstag. He retired from political life in 1928.

Bernstein died on 18 December 1932 in Berlin. A commemorative plaque is placed in his memory at Bozener Straße 18, Berlin - Schöneberg, where he lived from 1918 to his death.

Die Voraussetzungen des Sozialismus (1899) was Bernstein's most significant work. Bernstein was principally concerned with refuting Marx's predictions about the imminent and inevitable demise of capitalism, and Marx's consequent laissez faire policy which opposed socialist interventions before the demise. Bernstein pointed out simple facts that he took to be evidence that Marx's predictions were not being borne out: he noted that the centralization of capitalist industry, while significant, was not becoming wholescale and that the ownership of capital was becoming more, and not less, diffuse.

As to Marx's belief in the disappearance of the middleman, Bernstein declared that the entrepreneur class was being steadily recruited from the proletariat class, and therefore all compromise measures, such as the state regulation of the hours of labor, provisions for old age pensions, and so on, should be encouraged and taken advantage of. For this reason, Bernstein urged the laboring classes to take an active interest in politics. Bernstein also pointed out what he considered to be some of the flaws in Marx's labor theory of value.

In its totality, Bernstein's analysis formed a powerful critique of Marxism, and this led to his vilification among many orthodox Marxists. Bernstein remained, however, very much a socialist, albeit an unorthodox one: he believed that socialism would be achieved through capitalism, not through capitalism's destruction (as rights were gradually won by workers, their cause for grievance would be diminished, and consequently, so too would the foundation of revolution). During the intra - party debates about his ideas, Bernstein explained that, for him, the final goal of socialism was nothing; movement toward that goal was everything.

Although Marx would argue that free trade would be the quickest fulfillment of the capitalist system, and thus its end, Bernstein viewed protectionism as helping only a selective few, being fortschrittsfeindlich (anti - progressive), for its negative effects on the masses. Germany's protectionism, Bernstein argued, was only based on political expediency, isolating Germany from the world (especially from Britain), creating an autarky that would only result in conflict between Germany and the rest of the world.

He is also noted for being "one of the first socialists to deal sympathetically with the issue of homosexuality."