<Back to Index>

- General of the Imperial Japanese Army Seishirō Itagaki, 1885

- Field Marshal of the Imperial Japanese Army Prince Kan'in Kotohito, 1865

- General of the Imperial Japanese Army Iwane Matsui, 1878

PAGE SPONSOR

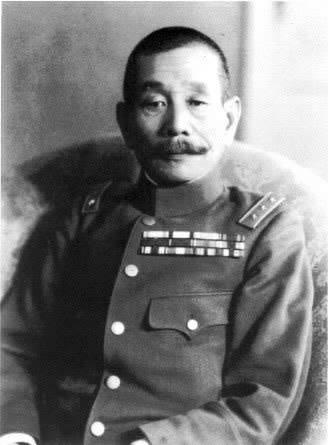

Seishirō Itagaki (板垣 征四郎 Itagaki Seishirō, 21 January 1885 – 23 December 1948) was a General in the Imperial Japanese Army in World War II and a War Minister.

Itagaki was born in Morioka city, Iwate prefecture, into a samurai class family formerly serving the Nanbu clan of Morioka Domain. He graduated from the Imperial Japanese Army Academy in 1904. He fought in the Russo - Japanese War in 1904 - 05.

From 1924 - 1926, Itagaki was a military attaché assigned to the Japanese embassy in China. On his return to Japan, he held a number of staff positions within the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff during 1926 - 1927 before being given a field command as commanding officer of the IJA 33rd Infantry Brigade based in China. His brigade was attached to the IJA 10th Division from 1927 - 1928. Itagaki was then transferred to command the IJA 33rd Infantry Regiment in China from 1928 – 1929, under the aegis of the Kwantung Army.

Itagaki rose to become Chief of the Intelligence Section of the Kwantung Army from 1931, in which capacity he helped plan the 1931 Mukden Incident that led to the Japanese seizure of Manchuria. He was subsequently a military advisor to Manchukuo from 1932 - 1934.

Itagaki became Vice Chief of Staff of the Kwantung Army from 1934, and Chief of Staff in 1936.

From 1937 to 1938 Itagaki was commander of the IJA 5th Division in China during the early part of the Second Sino - Japanese War. His Division took a leading part in the Battle of Beiping - Tianjin, Operation Chahar, and the Battle of Taiyuan. However in the Battle of Xuzhou his forces were repulsed during the Battle of Taierzhuang in the vicinity of Linyi that prevented them from coming to the aid of Rensuke Isogai's IJA 10th Division.

Recalled to Japan in 1938, Itagaki briefly served as War Minister from 1938 - 1939. On December 6, 1938, Itagaki proposed a national policy in accordance with Hakko Ichiu at the Five Ministers Conference, which was the Japanese highest decision making council, and the council made a decision of prohibiting the expulsion of the Jews in Japan, Manchuria, and China as Japanese national policy.

Itagaki returned to China again as chief of staff of the China Expeditionary Army from 1939 - 1941. However, the defeat of Japanese forces against the Soviet Red Army at Nomonhan in the summer of 1939 was a major blow to his career, and he was reassigned to command the Chosen Army in Korea, then considered a backwater post.

However, as the war situation continued to deteriorate for Japan, the Chosen Army was elevated to the Japanese 17th Area Army in 1945, with Itagaki still as commander in chief. He was then reassigned to the Japanese Seventh Area Army in Singapore and Malaya in April 1945. He surrendered Japanese forces in Southeast Asia to British Admiral Louis Mountbatten in Singapore on 12 September 1945.

After the war, he was taken into custody by the SCAP authorities and charged with war crimes, specifically in connection with the Japanese seizure of Manchuria, his escalation of the war against the Allies during his term as War Minister, and for allowing inhumane treatment of prisoners of war during his term as commander of Japanese forces in Southeast Asia. He was found guilty on counts 1, 27, 29, 31, 32, 35, 36 and 54 and was condemned to death in 1948 by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. Itagaki was hanged on 23 December 1948 at Sugamo Prison, Tokyo.

Prince Kan'in Kotohito (閑院宮載仁親王 Kan'in - no - miya Kotohito Shinnō OM, November 10, 1865 – May 21, 1945), was the sixth head of a cadet branch of the Japanese imperial family, and a career army officer who served as Chief of the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff from 1931 to 1940.

Prince Kotohito was born in Kyoto on November 10, 1865 as the sixteenth son of Prince Fushimi Kuniye (1802 – 1875). His father was twentieth head of the Fushimi - no - miya, one of the four shinnōke, branches of the Imperial Family which were eligible to succeed to the throne if the main line should die out. Since the infant mortality rate in the main imperial household was quite high, Emperor Kōmei, the father of Emperor Meiji, adopted Prince Kotohito as a potential heir. Prince Kotohito was thus the adopted brother of Emperor Meiji and a great uncle to both Emperor Shōwa and his consort, Empress Kōjun.

Prince Kotohito was initially sent to Sambō-in monzeki temple at the age of three to be raised as a Buddhist monk, but was selected in 1872 to revive the Kan'in - no - miya, another of the shinnōke households, which had gone extinct upon the death of the fifth head, Prince Naruhito.

On December 19, 1891, Prince Kotohiko married Sanjō Chieko (January 30, 1872 – March 19, 1947), a daughter of Prince Sanjō Sanetomi. The couple had seven children: five daughters and two sons

Prince Kan'in entered the Imperial Japanese Army Academy in 1877 and graduated in 1881. Emperor Meiji sent him as a military attaché to France in 1882 to study military tactics and technology. He graduated from the Army Staff College in 1894, specializing in cavalry. He commanded the 1st Cavalry Regiment from 1897 to 1899.

Prince Kan'in became a veteran of both the First Sino - Japanese War (1894 – 1895) and the Russo - Japanese War (1904 – 1905). He was appointed to command the 2nd Cavalry Brigade in 1901. He rose to the rank of lieutenant general in 1905 and became the commander of the IJA 1st Division in 1906, and the Imperial Guard Division in 1911. He was promoted to the rank of full general and became a Supreme War Councilor in 1912. He was further promoted to become the youngest field marshal in the Imperial Japanese Army in 1919.

In 1921, Prince Kan'in accompanied then Crown Prince Hirohito on his tour of Europe. He became Chief of the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff on December 1, 1931, replacing General Kanaya Hanzo.

During his mandate, the Imperial Japanese Army has been accused of committing many exactions against Chinese civilians including the Nanking massacre and the use of chemical and bacteriological weapons. Chemical weapons, such as tear gas, were used only sporadically in 1937, but in the spring of 1938 the Imperial Japanese Army began full scale use of sneeze and nausea gas (red), and from summer 1939, mustard gas (yellow) was used against both Kuomintang and Communist Chinese troops. Prince Kan'in transmitted to the Army the emperor's first directive (rinsanmei) authorizing the use of chemical weapons on July 28, 1937. He transmitted a second order on September 11 authorizing the deployment of special chemical warfare units to Shanghai. On April 11, 1938, Directive Number 11 was issued in his name, authorizing further use of poison gas in Inner Mongolia.

Prince Kan'in, among others within the army, opposed Prime Minister Yonai Mitsumasa's efforts to improve relations with the United States and the United Kingdom. He forced the resignation of War Minister General Hata Shunroku (1879 – 1962), thus bringing down the Yonai cabinet in July 1940. The Prince was a participant in the liaison conferences between the military chiefs of staff and the second cabinet of Prince Konoe Fumimaro (June 1940 – July 1941). Both he and Lieutenant General Tojo Hideki, the newly appointed War Minister, supported the Tripartite Pact between the Empire of Japan, Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy.

Prince Kan'in retired as Chief of the General Staff on October 3, 1940 and was succeeded by Sugiyama Hajime. He remained a member of the Supreme War Council and a senior advisor to the emperor on army matters. Field Marshal Prince Kan'in died in Odawara, Kanagawa at the Kan'in summer residence, possibly due to an infection due to inflamed hemorrhoids on May 21, 1945 and was accorded a state funeral.

The Prince was a strong supporter of State Shinto, with Kiichiro Hiranuma he set up the "Shintoist Rites Research Council" to research all ancient Shinto rites and practices. Other associates were Kuniaki Koiso, Lieutenant General Heisuke Yanagawa, who directed the Taisei Yokusankai and Chikao Fujisawa, member of the Diet of Japan, who proposed a law that Shinto should be reaffirmed as Japan's state religion.

His only son, Prince Kan'in Haruhito, succeeded him as the seventh and last head of the Kan'in - no - miya household.

His decorations included the Grand Order of Merit, Order of the Golden Kite (1st Class), and the Collar of the Supreme Order of the Chrysanthemum.

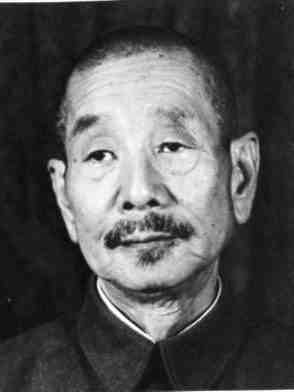

Iwane Matsui (松井 石根 Matsui Iwane, extra 27 July 1878 – 23 December 1948) was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army and the commander of the expeditionary forces sent to China in World War II. He was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to death by hanging by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East for responsibility over the Nanking Massacre.

Matsui was born in Aichi prefecture as the sixth son of a former samurai retainer of the Tokugawa clan of Owari han. Matsui graduated from the 9th class of the Imperial Japanese Army Academy in 1897. His classmates included future Prime Minister Nobuyuki Abe, and generals Sadao Araki, Jinzaburo Mazaki and Shigeru Honjō.

Matsui fought in the Russo - Japanese War of 1904 – 1905, and graduated from the 18th class of the Army Staff College in 1906. He became commanding officer of the 29th Regiment from 1919 to 1921.

From 1921 to 1922, Matsui was attached to the Vladivostok Expeditionary Force Staff for the Japanese Siberian Intervention against Bolshevik Red Army forces in eastern Russia. From 1922 to 1924, he was transferred to military intelligence and made head of the Harbin Special Services Agency in Manchuria. Matsui was then made commanding officer of the IJA 35th Infantry Brigade until 1925. From those posts he was sent to be head of the 2nd Bureau of the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff from 1925 to 1928, then attached to the Army General Staff until 1929 when he was promoted to major general and assigned command of the IJA 11th Division until 1931.

From 1931 to 1932, Matsui was a member of the Japanese delegation to the Geneva Disarmament Conference and then again attached to the Army General Staff until 1933.

Matsui attained the rank of general in 1933, and was appointed a member of the Supreme War Council until 1935, except for the period from 1933 to 1934 when he was Commander in Chief of the Taiwan Army. In 1933 he became one of the initiators of “Greater Asia Association”, and also established a “Taiwan - Asia Association”. He was also awarded the Order of the Rising Sun, 1st class for his career efforts, and went into retirement from active military service in 1935.

However, with the start of the Second Sino - Japanese War, Matsui was recalled to duty on 15 August 1937 to become the commander of the Japanese Shanghai Expeditionary Force (SEF) during the Battle of Shanghai. On leaving the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, Matsui remarked to War Minister Hajime Sugiyama that: "There's no solution except to break the power of Chiang Kai-shek by capturing Nanking. That is what I must do."

On 23 August, the SEF arrived in Shanghai, and was reinforced with the Japanese Tenth Army commanded by Lieutenant General Heisuke Yanagawa later in October. On 7 November, Japanese Central China Area Army (CCAA) was organized by combining the SEF and the 10th Army, with Matsui appointed as its commander - in - chief concurrently with that of the SEF. After winning the battles around Shanghai, the SEF suggested the Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo to attack Nanking. The CCAA was rearranged and Lieutenant General Prince Asaka (Yasuhiko), an uncle of Emperor Hirohito, was appointed as the commander of the SEF, while Matsui stayed as the commander of CCAA overseeing both the SEF and the 10th Army. The real nature of Matsui's authority is however difficult to establish as he was confronted with a member of the imperial family directly appointed by the Emperor. In anticipation of the attack on Nanking, Matsui issued orders to his armies that read:

Nanking is the capital of China and the capture thereof is an international affair; therefore, careful study should be made so as to exhibit the honor and glory of Japan and augment the trust of the Chinese people, and that the battle in the vicinity of Shanghai is aimed at the subjugation of the Chinese Army, therefore protect and patronize Chinese officials and people, as far as possible; the Army should always bear in mind not to involve foreign residents and armies in trouble and maintain close liaison with foreign authorities in order to avoid misunderstandings.

On 10 December 1937, the SEF began its attack on Nanking, and the Kuomintang forces that remained surrendered on 13 December 1937. The Nanking massacre began immediately afterwards. Matsui and Asaka marched triumphantly into Nanking on 17 December 1937.

While Matsui himself was not present during the beginning of the atrocities (he was ill at the time), he was aware of what his men were doing in the city, as were members of the Japanese foreign service who had followed the army into the city. Word began to trickle out of Nanking, and growing pressure was placed on the Imperial government to recall the SEF's officers.

Concerning atrocities in Nanking, Matsui wrote in his war journal about rapes (20 December) and looting (29 December) and wrote it was very much regrettable that these behaviors destroyed the reputation of the Imperial Japanese Army. He also mentioned "a number of abominable incidents within the past 50 days" at the memorial service for the war dead of the SEF held on 7 February and rebuked, in tears, the officers and the soldiers in the place, saying that atrocities done by a part of the army had damaged the reputation of the empire, such a thing should not happen in the Imperial Army, they should maintain discipline strictly and should never persecute innocent people, and so on.

Both Matsui and Asaka were recalled to Japan in 1938. Matsui retired again from the military, and returned to his hometown of Atami, Shizuoka prefecture. Along with several others in the community, he built a large statue of Kannon, the Buddhist Goddess of Mercy, facing in the direction of Nanking.

Arrested by the American occupation authorities after the surrender of Japan, Matsui was charged with war crimes in connection with the actions of the Japanese army in China. In 1948, the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE) found him guilty of class B and C war crimes, and he was hanged that December at Sugamo Prison, alongside six others, including Hideki Tōjō. He was 70 at the time of his death.

In court, Muto straightforwardly admitted that what the prosecutors dubbed "the Rape of Nanking" took place. There were many other Japanese witnesses who acknowledged that there were excesses of Japanese troops in Nanking, though their perceptions as to the scale of the atrocities varied.

Among the most candid witnesses was Ishii Itaro, the East Asia Bureau chief of the Foreign Ministry. He testified that he was briefed about the rape, arson, looting and murders from Foreign Ministry offices in Nanjing and Shanghai. In his autobiography, Ishii wrote that he and Foreign Minister Hirota Koki had warned the Army many times to take action.

In their decision, the Tribunal wrote:

The Tribunal is satisfied that Matsui knew what was happening. He did nothing, or nothing effective to abate these horrors. He did issue orders before the capture of the city enjoining propriety of conduct upon his troops and later he issued further orders to the same purport. These orders were of no effect as is now known, and as he must have known. It was pleaded in his behalf that at this time he was ill. His illness was not sufficient to prevent his conducting the military operations of his command nor to prevent his visiting the City for days while these atrocities were occurring. He was in command of the Army responsible for these happenings. He knew of them. He had the power, as he had the duty, to control his troops and to protect the unfortunate citizens of Nanking. He must be held criminally responsible for his failure to discharge this duty.

The first edition of The Rape of Nanking, by Iris Chang, followed the IMTFE's lead in blaming Matsui for the massacre arguing the traditional view that Matsui planned the invasion of Nanking and was Asaka's commanding officer during the Rape. Chang however revised her position in subsequent editions and insisted on the fact that Matsui was sick during the massacre and that Asaka was therefore the officer in charge.

James Yin and Shi Young's book of the same title also blames Asaka for the massacre, and portrays Matsui as a helpless figurehead stuck between a prince and an emperor. The truth is a matter of continued debate.