<Back to Index>

- President of the Provisional Government Georges - Augustin Bidault, 1899

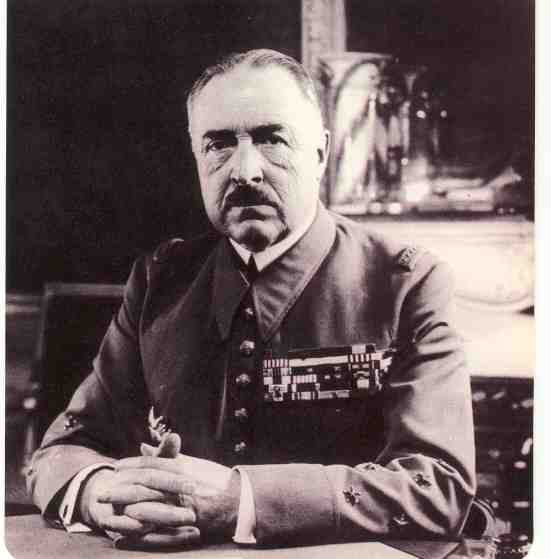

- General of the French Army Pierre Armand Gaston Bilotte, 1906

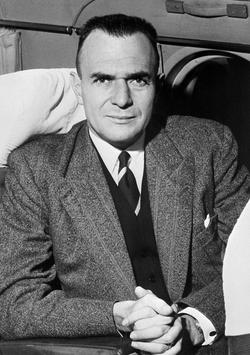

- Flying Ace Pierre Henri Clostermann, 1921

PAGE SPONSOR

Georges-Augustin Bidault (5 October 1899 – 27 January 1983) was a French politician. During World War II, he was active in the French Resistance. After the war, he served as foreign minister and prime minister on several occasions before he joined the Organisation armée secrète.

Bidault was born in Moulins, Allier. He studied in the Sorbonne and became a college history teacher. In 1932 he helped to found the Catholic Association of French Youth and the left wing anti - fascist newspaper l'Aube. He had a column in the paper and, among other things, protested against the Munich Agreement in 1938.

After the outbreak of the Second World War he joined the French army. He was captured during the Fall of France and was briefly imprisoned. After his release in July 1941, he became a teacher at the Lycée du Parc in Lyon and joined the Liberté group of French Resistance that eventually merged with Combat. Jean Moulin recruited him to organize an underground press and the Combat underground newspaper.

In his work in the resistance, he was helped by his private administrative assistant Laure Diebold.

Bidault participated in the forming of the Conseil National de la Résistance and, after the Gestapo captured Moulin, he became its new chairman. In 1944 he formed a Resistance Charter that recommended an extensive post war reform program. After the liberation of Paris he represented the Resistance in the victory parade. Charles de Gaulle appointed him as a foreign minister of his provisional government in 25 August. He was the founder of the Mouvement Républicain Populaire (MRP).

He was head of the French delegation to the San Francisco Conference, which established the UN, from April to June 1945. At the conference, France succeeded in gaining a permanent seat on the Security Council.

After World War II, Bidault served as foreign minister in Félix Gouin's provisional government in 1946. On 19 June 1946 the National Constituent Assembly elected him as president of the provisional government. His government, formed on 15 June, was composed of socialists, communists and Bidault's own MRP. In social policy, Bidault's government was notable for passing important pension and workman’s compensation laws. Bidault later became foreign minister once again. The government held elections to the National Assembly on 29 November after which Bidault resigned. His successor was Léon Blum.

Bidault served in various French governments, first as foreign minister under Paul Ramadier and Robert Schuman. In April 1947 he supported Ramadier's decision to expel the Communists from his government. Bidault had recently been to Moscow and was disturbed by the Soviet regime; he believed an agreement with Stalin was impossible.

In 1949 he became the President of the Council of Ministers (prime minister) but his government lasted only 8 months. In Henri Queuille's governments in 1950 – 1951 he held the office of Vice President of the Council and under Rene Pleven and Edgar Faure also the post of defense minister.

In 1952 Bidault became an honorary president of MRP. On 1 June 1953 President Vincent Auriol assigned him to form his own government but the National Assembly refused to give him the official mandate at 10 June. In 1953 Bidault became a presidential candidate but withdrew after the second round.

Bidault was foreign minister during the siege of the French garrison at Dien Bien Phu from March to May 1954. He protested to the Red Cross that the Viet Minh were shooting at clearly marked French medical evacuation flights, killing some of the evacuees. The ongoing fighting in Indochina had exhausted him; he was described by American secretary of state John Foster Dulles as "a deeply harassed man" and later by a historian as "on the verge of a nervous breakdown". Caught between his desires to end the war and to maintain the integrity of France's colonies, he vacillated between pressing the war, perhaps by asking the Americans for air support, or seeking a negotiated solution.

In April 1958 Bidault again became prime minister but did not form a cabinet and had a hand in forming the conservative Christian Democratic Movement. He also supported de Gaulle's presidency after the outbreak of the Algerian War of Independence.

In 1961 Bidault became President of the Executive Council of the Rally for French Algeria and opposed de Gaulle's policy of Algerian independence. He established his own National Resistance Council within the far right paramilitary organization Organisation de L'Armée Secrète (OAS). In June 1962 he was accused of conspiring against the state and stripped of his parliamentary immunity. He left for exile in Brazil. In 1967 he moved to Belgium and in 1968 returned to France after benefiting from an amnesty.

In his political memoirs, Bidault states that he was never involved in the OAS, and is not qualified to give any precise information about its heroic deeds.

Bidault died of a stroke in Cambo - les - Bains in January 1983.

Pierre Armand Gaston Billotte (March 8, 1906 – June 29, 1992) was a French Army officer and politician. He was the son of General Gaston Billotte, who commanded parts of the French Army at the start of World War II. Pierre Billotte was himself notable for his combat actions during the Battle of France.

Billotte is known for his extraordinary actions on 16 May 1940 during the battle at the French village of Stonne. Billotte served in the 1st Compagnie of the 41st Tank Battalion, equipped with the Char B1 heavy tank. Then Captain Billotte, commanding a Char B1 Bis tank nicknamed "Eure", was instrumental in capturing the village of Stonne, defended by elements of the German 8th Panzer Regiment. The village had already been the scene of fierce fighting before Billotte's action, having changed hands numerous times and lying on a strategic location on the road to Sedan. On 16 May, while under heavy fire from German tanks, Billotte and his B1 Bis managed to break through the German defenses and to destroy two German PzKpfw IV tanks, eleven PzKpfw III tanks and two enemy guns. Billotte's Char B1 Bis tank received 140 hits from enemy tanks and guns, but none were able to penetrate the tank's heavy armor.

Following the death of his father and the German victory in the Battle of France, Billotte was imprisoned by the German military. He escaped the next year, and was appointed by the Free French government - in - exile as head of the French Military Mission to Moscow. From 1942 to 1943, he served as chief of staff to Charles de Gaulle. After the Allied invasion of France, he was attached to the 2nd Armored Division. Later in 1944, he was put in command of the 10th Division, and after the liberation of French he became Assistant Chief of Staff of the French Army. From 1946 to 1950, he headed the French Military Mission to the UN. Following his retirement from active service, he served as Minister of National Defense (1955 – 1956) under Edgar Faure and as Minister of Overseas Departments and Territories (1966 – 1968) under Georges Pompidou.

Pierre Henri Clostermann (28 February 1921 – 22 March 2006) was a French flying ace, author, engineer, politician and sporting fisherman. Over his flying career he was awarded the Grand Croix of the French Légion d'Honneur, French Croix de Guerre, DFC and bar, Distinguished Service Cross (USA), Silver Star (USA), and the Air Medal (USA).

Clostermann was born in Curitiba, Brazil, into a French diplomatic family. He completed his secondary education in France and gained his private pilot's license in 1937.

On the outbreak of war the French authorities refused his application for service, so he traveled to Los Angeles to become a commercial pilot, studying at the California Institute of Technology. Clostermann joined the Free French Air Force in Britain in March 1942.

After training at RAF Cranwell and 61 OTU, Clostermann, a Sergeant Pilot, was posted in January 1943 to No. 341 Squadron RAF (known to the Free French as Groupe de Chasse n° 3/2 "Alsace"), flying the Supermarine Spitfire.

He scored his first two victories on 27 July 1943, destroying two Focke - Wulf Fw 190s over France.

In October 1943, Clostermann was commissioned and assigned to No. 602 Squadron RAF, remaining with the unit for the next ten months. He flew a variety of missions including fighter sweeps, bomber escorts, high altitude interdiction over the Royal Navy's Scapa Flow base, and strafing or dive bombing attacks on V-1 launch sites on the French coast. Clostermann served through D-Day and was one of the first Free French pilots to land on French soil, at temporary airstrip B-11, near Longues - sur - Mer, Normandy on 18 June 1944, touching French soil for the first time in more than four years. Clostermann was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross shortly afterwards, after which he was reassigned to French Air Force Headquarters.

In December 1944, Clostermann returned to the front line, on secondment to the RAF as a supernumerary Flight Lieutenant. Clostermann joined No. 274 Squadron RAF flying the new Hawker Tempest Mk V. In an aircraft which he dubbed Le Grand Charles, Clostermann flew an intensive and highly successful round of fighter sweeps, airfield attacks, "rat scramble" interceptions of Messerschmitt 262 jet fighters, and rail interdiction missions over northern Germany over the next two months.

In March 1945, Clostermann briefly served with No. 56 Squadron before a transfer to No. 3 Squadron. On 24 March 1945, he was wounded in the leg by German flak and after belly landing his badly damaged aircraft, he was hospitalized for one week. From April 8, he was commander of A Flight, No. 3 Squadron RAF. Clostermann was awarded a Bar to his DFC for his successful tour of duty. He had to bail out for the first time on 12 May 1945, when during a victory fly past, a Tempest collided with his aircraft, and as a result of this horrific collision the four planes of his flight went down, with three pilots dying. Clostermann's parachute opened just a few yards above ground. Clostermann continued operations with No. 122 Wing RAF until he left the military altogether on 27 July 1945 (rank: Wing Commander).

In his 432 sorties, Clostermann was credited officially with 23 victories (19 solo, 14 shared, most of them against fighters) and five "probables", with eight more "damaged". He also claimed 225 motor vehicles destroyed, 72 locomotives, five tanks and two E-boats (fast torpedo boats). Many references credit him with 29 to 33 victories, although these probably include his "ground" kills of enemy aircraft. Recent, more detailed analysis of his combat reports and squadron accounts indicate that his true score was 11 destroyed, with possibly another seven, for a total of 15 – 18 victories.

Clostermann wrote a very successful book, The Big Show (Le Grand Cirque), on his experiences in the war. One of the very first post war fighter pilot memoirs, its various editions have sold over two and a half million copies. William Faulkner commented that this is the finest aviation book to come out of World War II. The book was reprinted, in expanded form, in both paperback and hardcover editions in 2004. He also wrote Flames in the Sky (Feu du Ciel) (1957), a collection of heroic air combat exploits from both Allied and Axis sides.

After the war, Clostermann continued his career as an engineer, participating in the creation of Reims Aviation, supporting the Max Holste Broussard prototype, acting as a representative for Cessna, and working for Renault. In parallel, Clostermann had a successful political career, serving eight terms as a député (Member of Parliament) in the French National Assembly between 1946 and 1969.

He also briefly re-enlisted in the Armée de l'Air in 1956 – 57 to fly ground attack missions during the Algerian War. He subsequently wrote a novel based on his experiences there, entitled "Leo 25 Airborne".

During the 1982 Falklands War between Argentina and the U.K., Clostermann apparently praised Argentine pilots for their courage, perhaps as a result of personal ties formed while Argentinian Air Force pilots were being trained in France in the 1970s. As a result of this perceived "betrayal" of the RAF, Clostermann attracted hostility from parts of the English press. He also attracted controversy in France for his vehement anti - war stance in the run up to the 1991 Gulf War.

Clostermann was also a sporting fisherman of international repute.

On 6 June 2004, a road in Longues - sur - Mer, near temporary airstrip B-11, was named after Clostermann,