<Back to Index>

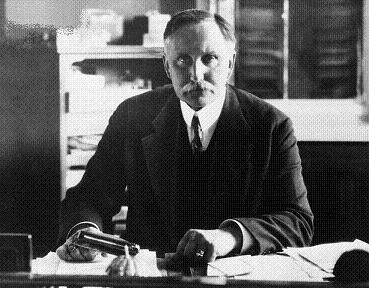

- Geographer and Geopolitician Karl Ernst Haushofer, 1869

- Geostrategist Nicholas John Spykman, 1893

PAGE SPONSOR

Karl Ernst Haushofer (August 27, 1869 – March 10, 1946) was a German general, geographer and geopolitician. Through his student Rudolf Hess, Haushofer's ideas may have influenced the development of Adolf Hitler's expansionist strategies, although Haushofer denied direct influence on the Nazi regime. Under the Nuremberg Laws, Haushofer's wife and children were categorized as mischlinge. His son, Albrecht, was issued a German Blood Certificate through the help of Hess.

Haushofer belonged to a family of artists and scholars. He was born in Munich, Germany, to Max Haushofer, a professor of economics, and Frau Adele Haushofer (née Fraas). On his graduation from the Munich Gymnasium (high school), Haushofer contemplated an academic career. However, service with the Bavarian army proved so interesting that he stayed to work, with great success, as an instructor in military academies and on the general staff.

In 1887, he entered the 1st Field Artillery regiment "Prinzregent Luitpold" and completed Kriegsschule, Artillerieschule and War Academy (Kingdom of Bavaria). In 1896, he married Martha Mayer - Doss (1877 – 1946) whose father was Jewish. They had two sons, Albrecht Haushofer and Heinz Haushofer {1906 - 1988}.

Haushofer continued his career as a professional soldier, serving in the army of Imperial Germany, and rising through the Staff Corp by 1899. In 1903 he began teaching at the Bavarian War Academy.

In November 1908 the army sent him to Tokyo to study the Japanese army and to advise it as an artillery instructor. He traveled with his wife via India and South East Asia and arrived in February 1909. Haushofer was received by the Japanese emperor and got to know many important people in politics and armed forces. In autumn 1909 he traveled with his wife for a month to Korea and Manchuria on the occasion of a railway construction. In June 1910 they returned to Germany via Russia and arrived one month later.

Shortly afterwards he began to suffer from several severe diseases and was given a leave from the army for three years. From 1911 – 1913 Haushofer would work on his doctorate of philosophy from Munich University for a thesis on Japan entitled: Dai Nihon, Betrachtungen über Groß - Japans Wehrkraft, Weltstellung und Zukunft (Reflections on Greater Japan's Military Strength, World Position, and Future). By World War I he had attained the rank of General, and commanded a brigade on the western front. He became disillusioned after Germany's loss and severe sanctioning, retiring with the rank of Major General in 1919. At this time, he forged a friendship with the young Rudolf Hess who would become his scientific assistant.

Haushofer entered academia with the aim of restoring and regenerating Germany. Haushofer believed the Germans' lack of geographical knowledge and geopolitical awareness to be a major cause of Germany’s defeat in World War I, as Germany had found itself with a poor alignment of allies and enemies. The fields of political and geographical science thus became his areas of specialty. In 1919 Haushofer became Privatdozent for political geography at Munich University and in 1933 professor.

Louis Pauwels, in his book "Monsieur Gurdjieff", describes Haushofer as a former student of George Gurdjieff; Others, including Pauwels, said that Haushofer created a Vril society; and that he was a secret member of the Thule Society.

After the establishment of the Nazi regime, Haushofer remained friendly with Rudolf Hess, who protected Haushofer and his wife from the racial laws of the Nazis, which deemed her a "half - Jew". During the pre - war years Haushofer was instrumental in linking Japan to the axis powers, acting in accordance with the theories of his book "Geopolitics of the Pacific Ocean".

After the July 20 Plot to assassinate Hitler, Haushofer's son Albrecht (1903 – 1945) went into hiding but was arrested on December 7, 1944 and put into the Moabit prison in Berlin. During the night of April 22 – 23, 1945 he and other selected prisoners like Klaus Bonhoeffer were walked out of the prison by an SS squad and shot. From September 24, 1945 on Karl Haushofer was informally interrogated by Father Edmund A. Walsh on behalf of the Allied forces to determine if he should stand trial at Nuremberg for war crimes. However, he was determined by Walsh not to have committed war crimes. On the night of March 10 – 11, 1946 he and his wife committed suicide in a secluded hollow on their Hartschimmelhof estate at Pähl / Ammersee. Both drank arsenic and the wife then hanged herself while Haushofer was obviously too weak to do so too.

Haushofer developed Geopolitik from widely varied sources, including the writings of Oswald Spengler, Alexander Humboldt, Karl Ritter, Friedrich Ratzel, Rudolf Kjellén and Halford J. Mackinder.

Geopolitik contributed to Nazi foreign policy chiefly in the strategy and justifications for lebensraum. The theories contributed five ideas to German foreign policy in the interwar period:

- the organic state

- lebensraum

- autarky

- pan-regions

- land power / sea power dichotomy.

Geostrategy as a political science is both descriptive and analytical like Political Geography, but adds a normative element in its strategic prescriptions for national policy. While some of Haushofer's ideas stem from earlier American and British geostrategy, German geopolitik adopted an essentialist outlook toward the national interest, oversimplifying issues and representing itself as a panacea. As a new and essentialist ideology, geopolitik found itself in a position to prey upon the post - WWI insecurity of the populace.

Haushofer's position in the University of Munich served as a platform for the spread of his geopolitical ideas, magazine articles and books. In 1922 he founded the Institute of Geopolitics in Munich, from which he proceeded to publicize geopolitical ideas. By 1924, as the leader of the German geopolitik school of thought, Haushofer would establish the Zeitschrift für Geopolitik monthly devoted to geopolitik. His ideas would reach a wider audience with the publication of Volk ohne Raum by Hans Grimm in 1926, popularizing his concept of lebensraum. Haushofer exercised influence both through his academic teachings, urging his students to think in terms of continents and emphasizing motion in international politics, and through his political activities. While Hitler's speeches would attract the masses, Haushofer's works served to bring the remaining intellectuals into the fold.

Geopolitik was in essence a consolidation and codification of older ideas, given a scientific gloss:

- Lebensraum was a revised colonial imperialism;

- Autarky a new expression of tariff protectionism;

- Strategic control of key geographic territories exhibiting the same thought behind earlier designs on the Suez and Panama canals; i.e., a view of controlling the land in the same way as those choke points control the sea

- Pan - regions (Panideen) based upon the British Empire, and the American Monroe Doctrine, Pan - American Union and hemispheric defense, whereby the world is divided into spheres of influence.

- Frontiers – His view of barriers between peoples not being political (i.e., borders) nor natural placements of races or ethnicities but as being fluid and determined by the will or needs of ethnic / racial groups.

The key reorientation in each dyad is that the focus is on land - based empire rather than naval imperialism.

Ostensibly based upon the geopolitical theory of American naval officer Alfred Thayer Mahan, and British geographer Halford J. Mackinder, German geopolitik adds older German ideas. Enunciated most forcefully by Friedrich Ratzel and his Swedish student Rudolf Kjellén, they include an organic or anthropomorphized conception of the state, and the need for self - sufficiency through the top - down organization of society. The root of uniquely German geopolitik rests in the writings of Karl Ritter who first developed the organic conception of the state that would later be elaborated upon by Ratzel and accepted by Hausfhofer. He justified lebensraum, even at the cost of other nations' existence because conquest was a biological necessity for a state's growth.

Ratzel's writings coincided with the growth of German industrialism after the Franco - Prussian war and the subsequent search for markets that brought it into competition with Britain. His writings served as welcome justification for imperial expansion. Influenced by Mahan, Ratzel wrote of aspirations for German naval reach, agreeing that sea power was self - sustaining, as the profit from trade would pay for the merchant marine, unlike land power. Haushofer was exposed to Ratzel, who was friends with Haushofer's father, a teacher of economic geography, and would integrate Ratzel's ideas on the division between sea and land powers into his theories, saying that only a country with both could overcome this conflict.

Haushofer's geopolitik expands upon that of Ratzel and Kjellén. While the latter two conceive of geopolitik as the state as an organism in space put to the service of a leader, Haushofer's Munich school specifically studies geography as it relates to war and designs for empire. The behavioral rules of previous geopoliticians were thus turned into dynamic normative doctrines for action on lebensraum and world power.

Haushofer defined geopolitik in 1935 as "the duty to safeguard the right to the soil, to the land in the widest sense, not only the land within the frontiers of the Reich, but the right to the more extensive Volk and cultural lands." Culture itself was seen as the most conducive element to dynamic special expansion. It provided a guide as to the best areas for expansion, and could make expansion safe, whereas projected military or commercial power could not. Haushofer even held that urbanization was a symptom of a nation's decline, evidencing a decreasing soil mastery, birthrate and effectiveness of centralized rule.

To Haushofer, the existence of a state depended on living space, the pursuit of which must serve as the basis for all policies. Germany had a high population density, whereas the old colonial powers had a much lower density, a virtual mandate for German expansion into resource rich areas. Space was seen as military protection against initial assaults from hostile neighbors with long range weaponry. A buffer zone of territories or insignificant states on one's borders would serve to protect Germany. Closely linked to this need, was Haushofer's assertion that the existence of small states was evidence of political regression and disorder in the international system. The small states surrounding Germany ought to be brought into the vital German order. These states were seen as being too small to maintain practical autonomy, even if they maintained large colonial possessions, and would be better served by protection and organization within Germany. In Europe, he saw Belgium, the Netherlands, Portugal, Denmark, Switzerland, Greece and the "mutilated alliance" of Austro - Hungary as supporting his assertion.

Haushofer's version of autarky was based on the quasi - Malthusian idea that the earth would become saturated with people and no longer able to provide food for all. There would essentially be no increases in productivity.

Haushofer and the Munich school of geopolitik would eventually expand their conception of lebensraum and autarky well past the borders of 1914 and "a place in the sun" to a New European Order, then to a New Afro - European Order, and eventually to a Eurasian Order. This concept became known as a pan - region, taken from the American Monroe Doctrine, and the idea of national and continental self - sufficiency. This was a forward looking refashioning of the drive for colonies, something that geopoliticians did not see as an economic necessity, but more as a matter of prestige, and putting pressure on older colonial powers. The fundamental motivating force would not be economic, but cultural and spiritual. Haushofer was, what is called today, a proponent of "Eurasianism", advocating a policy of German – Russian hegemony and alliance to offset an Anglo – American power structure's potentially dominating influence in Europe.

Beyond being an economic concept, pan - regions were a strategic concept as well. Haushofer acknowledges the strategic concept of the Heartland put forward by the British geopolitician Halford Mackinder. If Germany could control Eastern Europe and subsequently Russian territory, it could control a strategic area to which hostile seapower could be denied. Allying with Italy and Japan would further augment German strategic control of Eurasia, with those states becoming the naval arms protecting Germany's insular position.

Evidence points to a disconnect between geopoliticians and the Nazi leadership, although their practical tactical goals were nearly indistinguishable.

Rudolf Hess, Hitler's secretary who would assist in the writing of Mein Kampf, was a close student of Haushofer's. While Hess and Hitler were imprisoned after the Munich Putsch in 1923, Haushofer spent six hours visiting the two, bringing along a copy of Friedrich Ratzel's Political Geography and Clausewitz's On War. After WWII, Haushofer would deny that he had taught Hitler, and claimed that the National Socialist Party perverted Hess's study of geopolitik. He viewed Hitler as a half - educated man who never correctly understood the principles of geopolitik passed onto him by Hess, and Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop as the principal distorter of geopolitik in Hitler's mind. While Haushofer accompanied Hess on numerous propaganda missions, and participated in consultations between Nazis and Japanese leaders, he claimed that Hitler and the Nazis only seized upon half - developed ideas and catchwords. Furthermore, the Nazi party and government lacked any official organ that was receptive to geopolitik, leading to selective adoption and poor interpretation of Haushofer's theories. Ultimately, Hess and Konstantin von Neurath, Nazi Minister of Foreign Affairs, were the only officials Haushofer would admit had a proper understanding of geopolitik.

Father Edmund A. Walsh S.J., professor of geopolitics and dean at Georgetown University, who interviewed Haushofer after the allied victory in preparation for the Nuremberg trials, disagreed with Haushofer's assessment that geopolitik was terribly distorted by Hitler and the Nazis. He cites Hitler's speeches declaring that small states have no right to exist, and the Nazi use of Haushofer's maps, language and arguments. Even if distorted somewhat, Fr. Walsh felt that was enough to implicate Haushofer's geopolitik.

Haushofer also denied assisting Hitler in writing Mein Kampf, saying that he only knew of it once it was in print, and never read it. Fr. Walsh found that even if Haushofer did not directly assist Hitler, discernible new elements appeared in Mein Kampf, as compared to previous speeches made by Hitler. Geopolitical ideas of lebensraum, space for depth of defense, appeals for natural frontiers, balancing land and seapower, and geographic analysis of military strategy entered Hitler's thought between his imprisonment and publishing of Mein Kampf. Chapter XIV, on German policy in Eastern Europe, in particular displays the influence of the materials Haushofer brought Hitler and Hess while they were imprisoned.

Haushofer was never a member of the Nazi Party, and did voice disagreements with the party, leading to his brief imprisonment. Haushofer came under suspicion because of his contacts with left wing socialist figures within the Nazi movement (led by Gregor Strasser) and his advocacy of essentially a German – Russian alliance. This Nazi left wing had some connections to the Communist Party of Germany and some of its leaders, especially those who were influenced by the National Bolshevist philosophy of a German – Russian revolutionary alliance, as advocated by Ernst Niekisch, Julius Evola, Ernst Jünger, Hielscher and other figures of the "conservative revolution." He did profess loyalty to the Führer and make anti - Semitic remarks on occasion. However, his emphasis was always on space over race, believing in environmental rather than racial determinism. He refused to associate himself with anti - Semitism as a policy, especially because his wife was half - Jewish. Haushofer admits that after 1933 much of what he wrote was distorted under duress: his wife had to be protected by Hess's influence (who managed to have her awarded 'honorary German' status); his son was implicated in the July 20 plot to assassinate Hitler and was executed by the Gestapo; he himself was imprisoned in Dachau concentration camp for eight months; and his son and grandson were imprisoned for two - and - a - half months.

The notion of a contact between Haushofer and the Nazi establishment has been stressed by several authors. These authors have expanded Haushofer's contact with Hitler to a close collaboration while Hitler was writing Mein Kampf and made him one of the 'future Chancellor's many mentors'. Haushofer may have been a short term student of Gurdjieff, that he had studied Zen Buddhism, and that he had been initiated at the hands of Tibetan lamas, although these notions are debated.

The influence of Haushofer on Nazi ideology is dramatized in the 1943 short documentary film, Plan for Destruction. The film was nominated for an Academy Award.

Nicholas John Spykman (1893 – 1943) was a Dutch - American geostrategist, known as the "godfather of containment." As a political scientist he was one of the founders of the classical realist school in American foreign policy, transmitting Eastern European political thought into the United States. A Sterling Professor of International Relations, teaching as part of the Institute for International Studies at Yale University, one of his prime concerns was making his students geographically literate — geopolitics was impossible without geographic understanding. He was married to the children's novelist E.C. Spykman. He died of cancer at the age of 49.

Spykman published two books on foreign policy. America's Strategy in World Politics was published in 1942 near the entry of the United States into World War II. Concerned with balance of power, he argues that isolationism, relying on the oceans to protect the United States ("hemispheric" or "quarter defense"), was bound to fail. His object was to prevent a U.S. retreat, similar to U.S. policy following World War I. The Geography of the Peace was published the year after Spykman's death. In it he lays out his geostrategy, arguing that the balance of power in Eurasia directly affected United States security.

In his writings concerning geography and foreign policy, Spykman was somewhat of a geographical determinist. Since geography was "the most fundamentally conditioning factor because of its relative permanence," it was of primary relevance in analyzing a state's potential foreign policy.

N.J. Spykman could be considered as a disciple and critic of both geostrategists Alfred Mahan, of the United States Navy, and Halford Mackinder, the British geographer. His work is based on assumptions similar to Mackinder: the unity of world politics, and the unity of the world sea. He extends this to include the unity of the air. The exploration of the entire world means that the foreign policy of any nation will affect more than its immediate neighbors; it will affect the alignment of nations throughout the world's regions. Maritime mobility opened up the possibility of a new geopolitical structure: the overseas empire.

Spykman adopts Mackinder's divisions of the world, renaming some:

- the Heartland;

- the Rimland (analogous to Mackinder's "inner or marginal crescent"); and

- the Offshore Islands & Continents (Mackinder's "outer or insular crescent").

At the same time, because he gives credit to the strategic importance of maritime space and coastal regions, Spykman's analysis of the heartland is markedly different from Mackinder's. He does not see it as a region which will be unified by powerful transportation or communication infrastructure in the near future. As such, it won't be in a position to compete with the United States' sea power. Spykman agrees that the heartland offers a uniquely defensive position, but that is all Spykman grants the occupier of the heartland.

While the USSR encompassed a great expanse of land, its arable land remained in a small portion of its territory, mostly in the West. Indeed, the Soviet's raw materials were largely located to the West of the Ural mountains as well. Since the political and material center of gravity was in the Western part of the USSR, Spykman sees little possibility of the Soviets exerting much power in Central Asia.

Still, Russia was to remain the greatest land power in Asia, and could be a peacekeeper or a problem.

The Rimland (Mackinder's "Inner or Marginal Crescent") was divided into three sections:

- the European coast land;

- the Arabian - Middle Eastern desert land; and,

- the Asiatic monsoon land.

While Spykman accepts the first two as defined, he rejects the simple grouping of the Asian countries into one "monsoon land." India, the Indian Ocean littoral, and Indian culture were geographically and civilizationally separate from the Chinese lands.

The Rimland's defining characteristic is that it is an intermediate region, lying between the heartland and the marginal sea powers. As the amphibious buffer zone between the land powers and sea powers, it must defend itself from both sides, and therein lies its fundamental security problems. Spykman's conception of the Rimland bears greater resemblance to Alfred Thayer Mahan's "debated and debatable zone" than to Mackinder's inner or marginal crescent.

The Rimland has great importance coming from its demographic weight, natural resources, and industrial development. Spykman sees this importance as the reason that the Rimland will be crucial to containing the Heartland (whereas Mackinder had believed that the Outer or Insular Crescent would be the most important factor in the Heartland's containment).

There are two offshore continents flanking Eurasia: Africa and Australia. Spykman sees the two continents' geopolitical status as determined respectively by the state of control over the Mediterranean Sea and the "Asiatic Mediterranean." Neither has ever been the seat of significant political power — chaos prevents Africa from harnessing the resources of its tropical regions; Australia hasn't enough arable territory to serve as a base of power.

Other than the two continents there are offshore islands of significance are Britain and Japan, while the New World, buffered by the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans

Again, Spykman differs from Mackinder. Mackinder sees Eurasian wars as historically pitting the heartland against the sea powers for control of the rimland, establishing a land power - sea power opposition. Spykman states that historically battles have pitted Britain and rimland allies against Russia and its rimland allies, or Britain and Russia together against a dominating rimland power. In other words, the Eurasian struggle was not the sea powers containing the heartland, but the prevention of any power from ruling the rimland.

Spykman recalls Mackinder's famous dictum,

- Who controls eastern Europe rules the Heartland;

- Who controls the Heartland rules the World Island; and

- Who rules the World Island rules the World,

but disagrees, refashioning it thus:

- Who controls the rimland rules Eurasia;

- Who rules Eurasia controls the destinies of the world.

Therefore, British, Russian and U.S. power would play the key roles in controlling the European littoral, and thereby, the essential power relations of the world.

Spykman thought that it was in U.S. interests to leave Germany strong after World War II in order to be able to counter Russia's power. Strategically, there was no difference between Germany dominating all the way to the Urals, or Russia controlling all the way to Germany; both scenarios were equally threatening to the U.S.

Spykman predicted that Japan would lose the war in the Pacific, while China and Russia would remain to struggle against one another over boundaries. He also forecast the rise of China, becoming the dominant power in Asia, causing the U.S. to take responsibility for Japan's defense.

Spykman was opposed to European integration and argued that U.S. interests favored balanced power in Europe rather than integrated power. The U.S. was fighting a war against Germany to prevent Europe's conquest — it would not make sense to federalize and thereby unify Europe after a war fought to preserve balance.

John Foster Dulles and the founders of U.S. containment strategy would borrow heavily from Spykman, as well as Mackinder, when forging U.S. Cold War strategy.

- "Geography is the most fundamental factor in foreign policy because it is the most permanent."

- —from The Geography of the Peace

- "Plans for far - reaching changes in the character of international society are an intellectual by - product of all great wars."

- —from America's Strategy in World Politics

- "There are not many instances in history which show great and powerful states creating alliances and organizations to limit their own strength. States are always engaged in curbing the force of some other state. The truth of the matter is that states are interested only in a balance which is in their favor. Not an equilibrium, but a generous margin is their objective. There is no real security in being just as strong as a potential enemy; there is security only in being a little stronger. There is no possibility of action if one's strength is fully checked; there is a chance for a positive foreign policy only if there is a margin of force which can be freely used. Whatever the theory and rationalization, the practical objective is the constant improvement of the state's own relative power position. The balance desired is the one which neutralizes other states, leaving the home state free to be the deciding force and the deciding voice."

- —from America's Strategy in World Politics

- "[A] political equilibrium is neither a gift of the gods nor an inherently stable condition. It results from the active intervention of man, from the operation of political forces. States cannot afford to wait passively for the happy time when a miraculously achieved balance of power will bring peace and security. If they wish to survive, they must be willing to go to war to preserve a balance against the growing hegemonic power of the period."

- —from America's Strategy in World Politics

- "Nations which renounce the power struggle and deliberately choose impotence will cease to influence international relations either for evil or good."

- "Geographic facts do not change, but their meaning for foreign policy will."