<Back to Index>

- Painter Jean - Baptiste - Siméon Chardin, 1699

- Painter Jean - Baptiste Greuze, 1725

PAGE SPONSOR

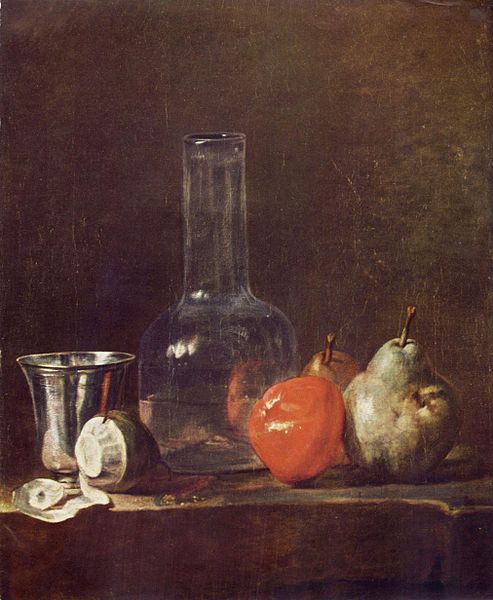

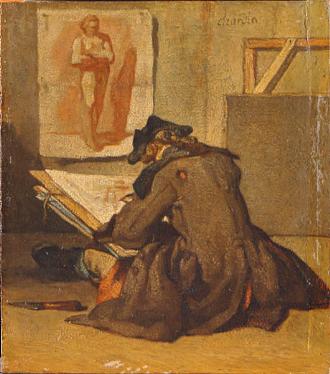

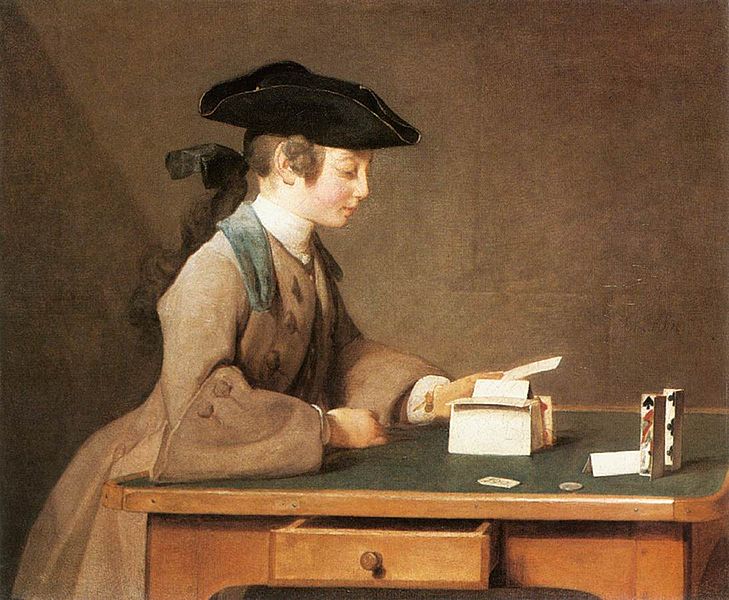

Jean - Baptiste - Siméon Chardin (2 November 1699 – 6 December 1779) was an 18th century French painter. He is considered a master of still life, and is also noted for his genre paintings which depict kitchen maids, children and domestic activities. Carefully balanced composition, soft diffusion of light, and granular impasto characterize his work.

Chardin was born in Paris, the son of a cabinet maker, and rarely left the city. He lived on the Left Bank near Saint - Sulpice until 1757, when Louis XV granted him a studio and living quarters in the Louvre.

Chardin entered into a marriage contract with Marguerite Saintard in 1723, whom he did not marry until 1731. He served apprenticeships with the history painters Pierre - Jacques Cazes and Noël - Nicolas Coypel, and in 1724 became a master in the Académie de Saint - Luc.

According to one nineteenth century writer, at a time when it was hard for unknown painters to come to the attention of the Royal Academy, he first found notice by displaying a painting at the "small Corpus Christi" (held eight days after the regular one) on the Place Dauphine (by the Pont Neuf). Van Loo, passing by in 1720, bought it and later assisted the young painter.

Upon presentation of The Ray in 1728, he was admitted to the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. The following year he ceded his position in the Académie de Saint - Luc. He made a modest living by "produc[ing] paintings in the various genres at whatever price his customers chose to pay him", and by such work as the restoration of the frescoes at the Galerie François I at Fontainebleau in 1731. In November 1731 his son Jean - Pierre was baptized, and a daughter, Marguerite - Agnès, was baptized in 1733. In 1735 his wife Marguerite died, and within two years Marguerite - Agnès had died as well.

Beginning in 1737 Chardin exhibited regularly at the Salon. He would prove to be a "dedicated academician", regularly attending meetings for fifty years, and functioning successively as counselor, treasurer and secretary, overseeing in 1761 the installation of Salon exhibitions.

His work gained popularity through reproductive engravings of his genre paintings (made by artists such as F.-B. Lépicié and P.-L. Sugurue), which brought Chardin income in the form of "what would now be called royalties". In 1744 he entered his second marriage, this time to Françoise - Marguerite Pouget. The union brought a substantial improvement in Chardin's financial circumstances. In 1745 a daughter, Angélique - Françoise, was born, but she died in 1746.

In 1752 Chardin was granted a pension of 500 livres by Louis XV. At the Salon of 1759 he exhibited nine paintings; it was the first Salon to be commented upon by Denis Diderot, who would prove to be a great admirer and public champion of Chardin's work. Beginning in 1761, his responsibilities on behalf of the Salon, simultaneously arranging the exhibitions and acting as treasurer, resulted in a diminution of productivity in painting, and the showing of 'replicas' of previous works. In 1763 his services to the Académie were acknowledged with an extra 200 livres in pension. In 1765 he was unanimously elected associate member of the Académie des Sciences, Belles - Lettres et Arts of Rouen, but there is no evidence that he left Paris to accept the honor. By 1770 Chardin was the 'Premier peintre du roi', and his pension of 1,400 livres was the highest in the Academy.

In 1772 Chardin's son, also a painter, drowned in Venice, a probable suicide. The artist's last known oil painting was dated 1776; his final Salon participation was in 1779, and featured several pastel studies. Gravely ill by November of that year, he died in Paris on December 6, at the age of 80.

Chardin worked very slowly and he only painted slightly more than 200 pictures (about four a year) total.

Chardin's work had little in common with the Rococo painting that dominated French art in the 18th century. At a time when history painting was considered the supreme classification for public art, Chardin's subjects of choice were viewed as minor categories. He favored simple yet beautifully textured still lifes, and sensitively handled domestic interiors and genre paintings. Simple, even stark, paintings of common household items (Still Life with a Smoker's Box) and an uncanny ability to portray children's innocence in an unsentimental manner (Boy with a Top) nevertheless found an appreciative audience in his time, and account for his timeless appeal.

Largely self taught, he was greatly influenced by the realism and subject matter of the 17th century Low Country masters. Despite his unconventional portrayal of the ascendant bourgeoisie, early support came from patrons in the French aristocracy, including Louis XV. Though his popularity rested initially on paintings of animals and fruit, by the 1730s he introduced kitchen utensils into his work (The Copper Cistern, ca.1735, Louvre). Soon figures populated his scenes as well, supposedly in response to a portrait painter who challenged him to take up the genre. Woman Sealing a Letter (ca. 1733), which may have been his first attempt, was followed by half - length compositions of children saying grace, as in Le Bénédicité, and kitchen maids in moments of reflection. These humble scenes deal with simple, everyday activities, yet they also have functioned as a source of documentary information about a level of French society not hitherto considered a worthy subject for painting. The pictures are noteworthy for their formal structure and pictorial harmony. Chardin has said about painting, "Who said one paints with colors? One employs colors, but one paints with feeling."

Chardin frequently painted replicas of his compositions — especially his genre paintings, nearly all of which exist in multiple versions which in many cases are virtually indistinguishable. Beginning with The Governess (1739, in the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa), Chardin shifted his attention from working class subjects to slightly more spacious scenes of bourgeoise life.

In 1756 he returned to the subject of the still life. In the 1770s his eyesight weakened and he took to painting in pastels, a medium in which he executed portraits of his wife and himself. His works in pastels are now highly valued. Chardin's extant paintings, which number about 200, are in many major museums, including the Louvre.

Chardin's influence on the art of the modern era was wide ranging, and has been well documented. Édouard Manet's half - length Boy Blowing Bubbles and the still lifes of Paul Cézanne are equally indebted to their predecessor. He was one of Henri Matisse's most admired painters; as an art student Matisse made copies of four Chardin paintings in the Louvre. Chaim Soutine's still lifes looked to Chardin for inspiration, as did the paintings of Georges Braque, and later, Giorgio Morandi. In 1999 Lucian Freud painted and etched several copies after The Young Schoolmistress (National Gallery, London).

Jean-Baptiste Greuze (21 August 1725 – 4 March 1805) was a French painter.

He was born at Tournus, Burgundy. He is generally said to have formed his own talent; this is, however, true only in the most limited sense, for at an early age his inclinations, though thwarted by his father, were encouraged by a Lyonnese artist named Grandon, or Grondom, who enjoyed during his lifetime considerable reputation as a portrait painter. Grandon not only persuaded the father of Greuze to give way to his son's wishes, and permit the lad to accompany him as his pupil to Lyon, but, when at a later date he himself left Lyon for Paris — where his son - in - law Grétry the celebrated composer enjoyed the height of favor — Grandon carried young Greuze with him.

Settled in Paris, Greuze worked from the living model in the school of the Royal Academy, but did not attract the attention of his teachers; and when he produced his first picture, "Le Père de famille expliquant la Bible a ses enfants," considerable doubt was felt and shown as to his share in its production. By other and more remarkable works of the same class Greuze soon established his claims beyond contest, and won for himself the notice and support of the well known connoisseur La Live de Jully, the brother - in - law of Madame d'Epinay. In 1755 Greuze exhibited his "Aveugle trompé," upon which, presented by Pigalle the sculptor, he was immediately agréé by the Academy.

Towards the close of the same year he left France for Italy, in company with the Abbé Louis Gougenot, who had deserted from the magistrature — although he had obtained the post of conseiller au Châtelet in order to take the petit collet. Gougenot had some acquaintance with the arts, and was highly valued by the Academicians, who, during his journey with Greuze, elected him an honorary member of their body on account of his studies in mythology and allegory; his acquirements in these respects are said to have been largely utilized by them, but to Greuze they were of doubtful advantage, and he lost rather than gained by this visit to Italy in Gougenot's company. He had undertaken it probably in order to silence those who taxed him with ignorance of great models of style, but the Italian subjects which formed the entirety of his contributions to the Salon of 1757 showed that he had been put on a false track, and he speedily returned to the source of his first inspiration.

In 1759, 1761 ("L'accordée de village", Louvre), and 1763 Greuze exhibited with ever increasing success; in 1765 he reached the zenith of his powers and reputation. In that year he was represented with no less than thirteen works, among which may be cited "La Jeune Fille qui pleure son oiseau mort", "La Bonne Mère", "Le Mauvais fils puni" (Louvre) and "La Malediction paternelle" (Louvre). The Academy took occasion to press Greuze for his diploma picture, the execution of which had been long delayed, and forbade him to exhibit on their walls until he had complied with their regulations. "J'ai vu la lettre," says Diderot, "qui est un modèle d'honnêteté et d'estime; j'ai vu la réponse de Greuze, qui est un modèle de vanité et d'impertinence: il fallait appuyer cela d'un chef - d'œuvre, et c'est ce que Greuze n'a pas fait." (I have read the letter, which is a model of honesty and reverence; I have seen Greuze's response, which is a model of vanity and impertinence: he should have backed it up with a masterpiece, and that's precisely what he didn't do.)

Greuze wished to be received as a historical painter, and produced a work which he intended to vindicate his right to despise his qualifications as a peintre de genre. This unfortunate canvas "Sévère et Caracalla" (Louvre) was exhibited in 1769 side by side with Greuze's portrait of "Jeaurat" (Louvre) and his admirable "Petite Fille au chien noir". The Academicians received their new member with all due honors, but at the close of the ceremonies the Director addressed Greuze in these words "Monsieur, l'Académie vous a reçu, mais c'est comme peintre de genre; elle a eu égard à vos anciennes productions, qui sont excellentes, et elle a fermé les yeux sur celle-ci, qui n'est digne ni d'elle ni de vous." (Sir, the Academy has accepted you, but only as peintre de genre; the Academy has respect for your former productions, which are excellent, but she has shut her eyes to this one, which is unworthy, both of her and of you yourself.) Greuze, greatly incensed, quarreled with his confreres, and ceased to exhibit until, in 1804, the Revolution had thrown open the doors of the Academy to all the world.

In the following year, on 4 March 1805, he died in the Louvre in great poverty. He had been in receipt of considerable wealth, which he had dissipated by extravagance and bad management (as well as embezzlement by his wife), so that during his closing years he was forced even to solicit commissions which his enfeebled powers no longer enabled him to carry out with success. "At the funeral of the long neglected old man, a young woman deeply veiled and overcome with emotion plainly visible through her veil, laid upon the coffin, just before its removal, a bouquet of immortelles and withdrew to her devotions. Around the stem was a paper inscribed: These flowers offered by the most grateful of his students are emblems of his glory. It was Mlle Mayer, later the friend of Prudhon."

The brilliant reputation which Greuze acquired seems to have been due, not to his accomplishments as a painter — for his practice is evidently that current in his own day — but to the character of the subjects which he treated. That return to nature which inspired Rousseau's attacks upon an artificial civilization demanded expression in art.

Diderot, in Le Fils naturel and Père de famille, tried to turn the vein of domestic drama to account on the stage; that which he tried and failed to do, Greuze, in painting, achieved with extraordinary success, although his works, like the plays of Diderot, were affected by that very artificiality against which they protested. The touch of melodramatic exaggeration, however, which runs through them finds an apology in the firm and brilliant play of line, in the freshness and vigor of the flesh tints, in the enticing softness of expression, by the alluring air of health and youth, by the sensuous attractions, in short, with which Greuze invests his lessons of bourgeois morality. As Diderot said of "La Bonne mère," il a prêché à la population; and a certain piquancy of contrast is the result which never fails to obtain admirers.

"La Jeune Fille à l'agneau" fetched, indeed, at the Pourtal's sale in 1865, no less than 1,000,000 francs. One of Greuze's pupils, Madame Le Doux, imitated with success the manner of her master; his daughter and granddaughter, Madame de Valory, also inherited some traditions of his talent. Madame de Valory published in 1813 a comédie - vaudeville, Greuze, ou l'accorde de village, to which she prefixed a notice of her grandfather's life and works, and the Salons of Diderot also contain, besides many other particulars, the story at full length of Greuze's quarrel with the Academy. Four of the most distinguished engravers of that date, Massard père, Flipart, Gaillard and Levasseur, were specially entrusted by Greuze with the reproduction of his subjects, but there are also excellent prints by other engravers, notably by Cars and Le Bas.

In the second chapter of Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes story The Valley of Fear, Holmes' discussion of his enemy Professor Moriarty involves a Greuze painting, intended to illustrate Moriarty's wealth despite his small income.

In the sixth part of The Leopard, a novel by the Italian writer Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, the Prince of Salina watches a Greuze painting, La Mort du Juste, and he starts thinking about death when his nephew Tancredi comes and asks "Are you courting death ?"

In Agatha Christie's "The Murder at the Vicarage," Miss Marple mentions her nephew considers another character "the perfect Greuze."

In the sixteenth chapter of E.M. Forster's novel Maurice, Clive mentions that he finds himself unable to approach Greuze's "subject matter" from anything more than purely aesthetic perspective, contrasting Greuze's work with that of the Greek sculptors in the process.

Chinese author Xiao Yi mentions Greuze's work The Broken Pitcher throughout the first half of her novel Blue Nails. The Broken Pitcher is also mentioned in the first scene of the Jean - Paul Sartre play, The Respectful Prostitute.