<Back to Index>

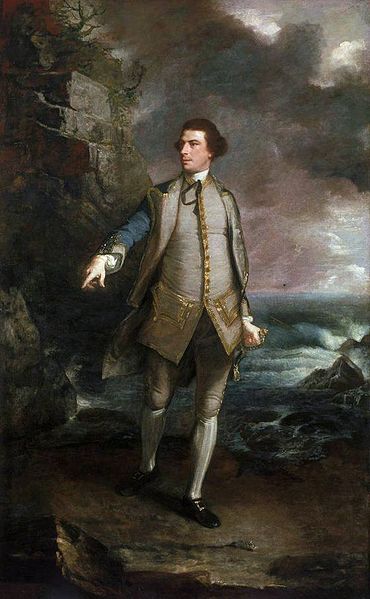

- Painter Thomas Gainsborough, 1727

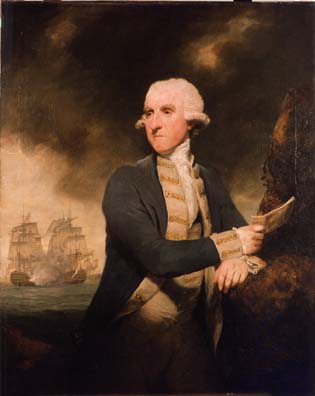

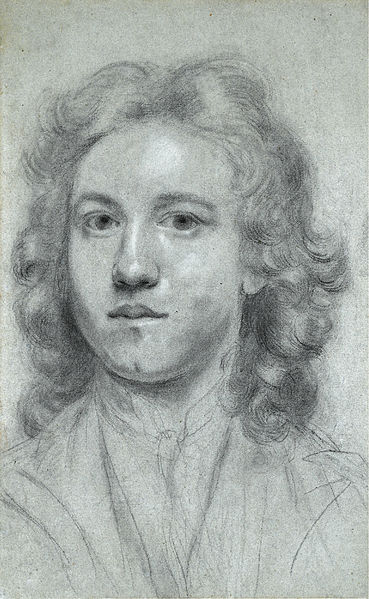

- Painter Joshua Reynolds, 1723

PAGE SPONSOR

Thomas Gainsborough (christened 14 May 1727 – 2 August 1788) was an English portrait and landscape painter. He was born the youngest son of John Gainsborough, a weaver in Suffolk, and, in 1740, left home to study art in London with Hubert Gravelot, Francis Hayman and William Hogarth. In 1746, he married Margaret Burr, and the couple became the parents of two daughters. He moved to Bath in 1759 where fashionable society patronized him, and he began exhibiting in London. In 1769, he became a founding member of the Royal Academy, but his relationship with the organization was thorny and he sometimes withdrew his work from exhibition. Gainsborough moved to London in 1774, and painted portraits of the King and Queen, but the King was obliged to name as royal painter Gainsborough's rival Joshua Reynolds. In his last years, Gainsborough painted relatively simple landscapes and is credited (with Richard Wilson) as the originator of the 18th century British landscape school. Gainsborough died of cancer in 1788 and is interred at St. Anne's Church, Kew, Surrey. He painted quickly and his later pictures are characterized by a light palette and easy strokes. He preferred landscapes to portraits. Cecil Kellaway portrayed Gainsborough in the 1945 film Kitty.

Thomas Gainsborough was born in Sudbury, Suffolk, the youngest son of John Gainsborough, a weaver and maker of woolen goods, and the sister of the Reverend Humphry Burroughs. At the age of thirteen he impressed his father with his penciling skills so that he let him go to London to study art in 1740. In London he first trained under engraver Hubert Gravelot but eventually became associated with William Hogarth and his school. He assisted Francis Hayman in the decoration of the supper boxes at Vauxhall Gardens, and contributed to the decoration of what is now the Thomas Coram Foundation for Children.

In 1746, Gainsborough married Margaret Burr, an illegitimate daughter of the Duke of Beaufort, who settled a £200 annuity on the couple. The artist's work, then mainly composed of landscape paintings, was not selling very well. He returned to Sudbury in 1748 – 1749 and concentrated on the painting of portraits.

In 1752, he and his family, now including two daughters, moved to Ipswich. Commissions for personal portraits increased, but his clientele included mainly local merchants and squires. He had to borrow against his wife's annuity.

In 1759, Gainsborough and his family moved to Bath, living at number 17 The Circus. There, he studied portraits by van Dyck and was eventually able to attract a fashionable clientele. In 1761, he began to send work to the Society of Arts exhibition in London (now the Royal Society of Arts, of which he was one of the earliest members); and from 1769 on, he submitted works to the Royal Academy's annual exhibitions. He selected portraits of well known or notorious clients in order to attract attention. These exhibitions helped him acquire a national reputation, and he was invited to become one of the founding members of the Royal Academy in 1769. His relationship with the academy, however, was not an easy one and he stopped exhibiting his paintings there in 1773.

In 1774, Gainsborough and his family moved to London to live in Schomberg House, Pall Mall. In 1777, he again began to exhibit his paintings at the Royal Academy, including portraits of contemporary celebrities, such as the Duke and Duchess of Cumberland. Exhibitions of his work continued for the next six years.

In 1780, he painted the portraits of King George III and his queen and afterwards received many royal commissions. This gave him some influence with the Academy and allowed him to dictate the manner in which he wished his work to be exhibited. However, in 1783, he removed his paintings from the forthcoming exhibition and transferred them to Schomberg House.

In 1784, royal painter Allan Ramsay died and the King was obliged to give the job to Gainsborough's rival and Academy president, Joshua Reynolds. Gainsborough remained the Royal Family's favorite painter, however. At his own express wish, he was buried at St. Anne's Church, Kew, where the Family regularly worshiped.

In his later years, Gainsborough often painted relatively simple, ordinary landscapes. With Richard Wilson, he was one of the originators of the eighteenth century British landscape school; though simultaneously, in conjunction with Sir Joshua Reynolds, he was the dominant British portraitist of the second half of the 18th century.

He died of cancer on 2 August 1788 at the age of 61 and is interred at St. Anne's Church, Kew, Surrey (located on Kew Green). He is buried next to Francis Bauer, the famous botanical illustrator. As of 2011, an appeal is underway to pay the costs of restoration of his tomb.

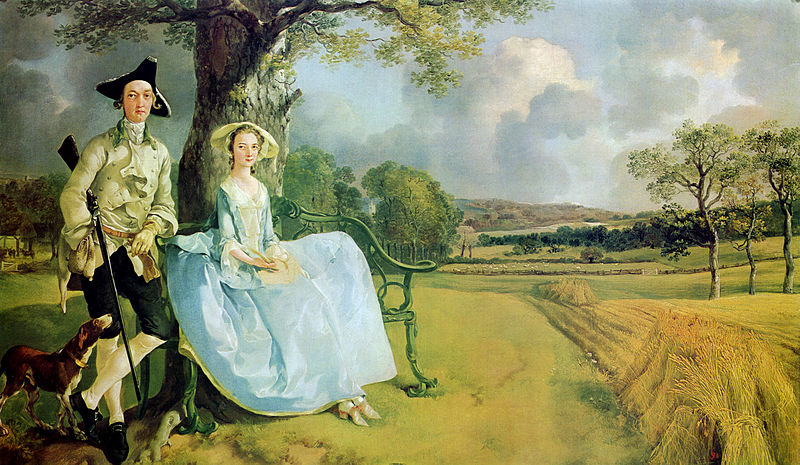

Gainsborough was noted for the speed with which he applied his paint, and he worked more from his observations of nature (and of human nature) than from any application of formal academic rules. The poetic sensibility of his paintings caused Constable to say, "On looking at them, we find tears in our eyes and know not what brings them." He himself said, "I'm sick of portraits, and wish very much to take my viol - da - gam and walk off to some sweet village, where I can paint landskips (sic) and enjoy the fag end of life in quietness and ease." This likeness of landscapes is shown in the way he merged the figures of the portraits with the scenes behind them. His later work was characterized by a light palette and easy, economical strokes.

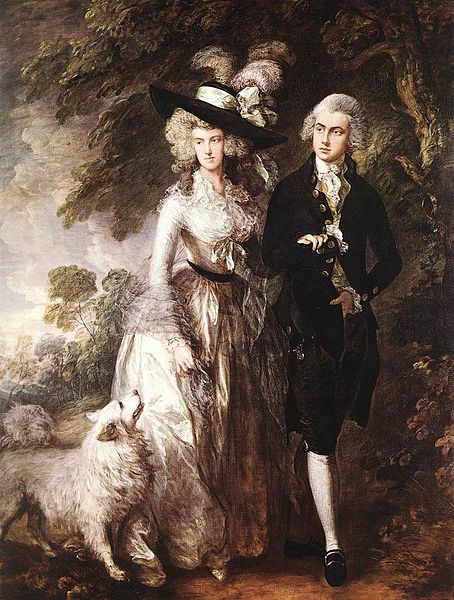

His most famous works, such as Portrait of Mrs. Graham; Mary and Margaret: The Painter's Daughters; William Hallett and His Wife Elizabeth, nee Stephen, known as The Morning Walk; and Cottage Girl with Dog and Pitcher, display the unique individuality of his subjects.

Gainsborough's only known assistant was his nephew, Gainsborough Dupont. In the last year of his life he collaborated with John Hoppner in painting a full length portrait of Charlotte, Countess Talbot.

Sir Joshua Reynolds RA FRS FRSA (16 July 1723 – 23 February 1792) was an influential 18th century English painter, specializing in portraits and promoting the "Grand Style" in painting which depended on idealization of the imperfect. He was one of the founders and first President of the Royal Academy. King George III appreciated his merits and knighted him in 1769.

Reynolds was born in Plympton, Devon, on 16 July 1723. As one of ten (maybe eleven) children and the son of the village school master, Reynolds was restricted to a formal education provided by his father. He exhibited a natural curiosity and, as a boy, came under the influence of Zachariah Mudge, whose Platonistic philosophy stayed with him all his life. Reynolds made extracts into his commonplace book from Theophrastus, Plutarch, Seneca, Marcus Antonius, Ovid, William Shakespeare, John Milton, Alexander Pope, John Dryden, Joseph Addison, Richard Steele, Aphra Behn and passages on art theory by Leonardo da Vinci, Charles Alphonse Du Fresnoy and André Félibien. The work that came to have the most influential impact on Reynolds was Jonathan Richardson's An Essay on the Theory of Painting (1715). Reynolds' annotated copy was lost for nearly two hundred years when it appeared in a Cambridge bookshop, inscribed with the signature ‘J. Reynolds Pictor’.

Showing an early interest in art, Reynolds was apprenticed in 1740 to the fashionable portrait painter Thomas Hudson, with whom he remained until 1743. In 1749, Reynolds became friend with Augustus Keppel, a naval officer, and they both sailed on the Centurion to the Mediterranean. Whilst on board, Reynolds wrote later, "I had the use of his cabin and his study of books, as if they had been my own". From 1749 to 1752, he spent over two years in Italy, where he studied the Old Masters and acquired a taste for the "Grand Style". Unfortunately, whilst in Rome, Reynolds suffered a severe cold which left him partially deaf, and, as a result, he began to carry a small ear trumpet with which he is often pictured. From 1753 until the end of his life, he lived in London, his talents gaining recognition soon after his arrival in France.

By 1761 Reynolds could command a fee of 80 Guineas for a full length portrait (Mr Fane); in 1764 he was paid 100 Guineas for a portrait of Lord Burghersh.

With his rival Thomas Gainsborough, Reynolds was the dominant English portraitist of 'the Age of Johnson'. It is said that in his long life he painted as many as three thousand portraits.

Much of the clothing shown in Reynolds' paintings was executed either by his pupils, his studio assistant Giuseppe Marchi, or by the specialist drapery painter Peter Toms James Northcote, his pupil, wrote that "the imitation of particular stuffs is not the work of genius, but is to be acquired easily by practice, and this was what his pupils could do by care and time more than he himself chose to bestow; but his own slight and masterly work was still the best."

Although not principally known for his landscapes, Reynolds did paint in this genre. He had an excellent vantage from his house on Richmond Hill, and painted the view in about 1780.

Reynolds worked long hours in his studio, rarely taking a holiday. He was both gregarious and keenly intellectual, with a great number of friends from London's intelligentsia, numbered among whom were Dr Samuel Johnson, Oliver Goldsmith, Edmund Burke, Giuseppe Baretti, Henry Thrale, David Garrick and fellow artist Angelica Kauffmann. Johnson said in 1778: "Reynolds is too much under Fox and Burke at present. He is under the Fox star and the Irish constellation [meaning Burke]. He is always under some planet".

Because of his popularity as a portrait painter, Reynolds enjoyed constant interaction with the wealthy and famous men and women of the day, and it was he who first brought together the famous figures of "The" Club. “The Club” was founded in 1764 and met in the suite of rooms on the first floor of the Turks Head, 9 Gerrard Street, now marked by a plaque. Original members included Burke, Langton, Beauclerk, Goldsmith, Chamier, Hawkins and Nugent, to be joined later by Garrick, Boswell and Sheridan. In 10 years the membership had risen to 35. “The Club” met at 7 p.m. every Monday evening for supper and conversation and would continue into the early hours of Tuesday morning. In later years, ”The Club” met fortnightly during Parliamentary sessions. When in 1783 the landlord of the Turks Head died and the property was sold as a dwelling house, “The Club” moved to Sackville Street.

In the Battle of Ushant with the French in 1778, Lord Keppel commanded the Channel Fleet and the outcome resulted in no clear winner; Keppel ordered to renew the attack and this was obeyed except by Sir Hugh Palliser, who commanded the rear, and the French escaped bombardment. A dispute between Keppel and Palliser arose and Palliser brought charges of misconduct and neglect of duty against Keppel and the Admiralty decided to court martial him. On 11 February 1779 Keppel was acquitted of all charges and became a national hero. One of Keppel's lawyers commissioned Sir Nathaniel Dance - Holland to paint a portrait of Keppel but Keppel redirected it to Reynolds. Reynolds alluded to Keppel's trial in the painting by having him have his hand on his sword, reflecting the presiding officer's words at the court martial: "In delivering to you your sword, I am to congratulate you on its being restored to you with so much honor".

On 10 August 1784 Allan Ramsay died and the office of Principal Painter in Ordinary to the King therefore became vacant. Gainsborough felt that he had a good chance of securing it but Reynolds felt that he deserved it and threatened to resign the presidency of the Royal Academy if he did not receive it. Reynolds noted in his pocket book: "Sept. 1, 2½, to attend at the Lord Chancellor's Office to be sworn in painter to the King". However this did not make Reynolds happy, as he wrote to Boswell: "If I had known what a shabby miserable place it is, I would not have asked for it; besides as things have turned out I think a certain person is not worth speaking to, nor speaking of", presumably meaning the King. Reynolds wrote to Jonathan Shipley, Bishop of St Asaph, a few weeks later: "Your Lordship congratulation on my succeeding Mr. Ramsay I take very kindly but it is a most miserable office, it is reduced from two hundred to thirty - eight pounds per annum, the Kings Rat catcher I believe is a better place, and I am to be paid only a fourth part of what I have from other people, so that the Portraits of their Majesties are not likely to be better done now, than they used to be, I should be ruined if I was to paint them myself".

In 1788 Reynolds painted the portrait of Lord Heathfield, who became a national hero for his successful defense of Gibraltar during its Great Siege from 1779 to 1783 against the combined forces of France and Spain. Heathfield is depicted against a background of clouds and cannon smoke, wearing the uniform of the 15th Light Dragoons and clasping the key of the Rock, its chain wrapped twice around his right hand. John Constable said in the 1830s that it was "almost a history of the defense of Gibraltar". Desmond Shawe - Taylor has claimed that the portrait may have a religious meaning, Heathfield holding the key similar to St Peter (Jesus' "rock") possessing the keys to Heaven, Heathfield "the rock upon which Britannia builds her military interests".

In 1789 he lost the sight of his left eye, which finally forced him into retirement. In 1791 James Boswell dedicated his Life of Samuel Johnson to Reynolds. Reynolds agreed with Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France and, writing in early 1791, expressed his belief that the ancien régime of France had fallen due to spending too much time tending

"to the splendor of the foliage, to the neglect of the stirring the earth about the roots. They cultivated only those arts which could add splendor to the nation, to the neglect of those which supported it – They neglected Trade & substantial Manufacture... but does it follow that a total revolution is necessary that because we have given ourselves up too much to the ornaments of life, we will now have none at all".

When attending a dinner at Holland House, Fox's niece Caroline was sat next to Reynolds and "burst out into glorification of the Revolution – and was grievously chilled and checked by her neighbor's cautious and unsympathetic tone".

On 4 June 1791 at a dinner at the Freemasons' Tavern to mark the King's birthday, Reynolds drank to the toasts "GOD save the KING!" and "May our glorious Constitution under which the arts flourish, be immortal!", in what was reported by the Public Advertiser as "a fervour truly patriotick". Reynolds "filled the chair with a most convivial glee". He returned to town from Burke's house in Beaconsfield and Edmond Malone wrote that "we left his carriage at the Inn at Hayes, and walked five miles on the road, in a warm day, without his complaining of any fatigue".

Later that month Reynolds suffered from a swelling over his left eye and had to be purged by a surgeon. In October he was too ill to take the President's chair and in November Fanny Burney recorded that

"I had long languished to see that kindly zealous friend, but his ill health had intimidated me from making the attempt": "He had a bandage over one eye, and the other shaded with a green half - bonnet. He seemed serious even to sadness, though extremely kind. ‘I am very glad,’ he said, in a meek voice and dejected accent, ‘to see you again, and I wish I could see you better! but I have only one ye now, and hardly that.’ I was really quite touched".

On 5 November Reynolds, fearing he may not have an opportunity to write a will, wrote a memorandum intended to be his last will and testament, with Edmund Burke, Edmond Malone and Philip Metcalfe named as executors. On 10 November Reynolds wrote to Benjamin West to resign the Presidency, but the General Assembly agreed that Reynolds should be re-elected, with Sir William Chambers and West to deputize for him.

The doctors Richard Warren and Sir George Baker believed Reynolds' illness to be psychological and they bled his neck "with a view of drawing the humor from his eyes" but the effect of this in the view of his niece was that it seemed "as if the 'principle of life' were gone" from Reynolds. On New Year's Day 1792 Reynolds became "seized with sickness" and from that point onward could not keep down food. Reynolds died on 23 February 1792 in his house in Leicester Fields in London between eight and nine in the evening.

Burke was present on the night Reynolds died, and he was moved within hours to write a eulogy of Reynolds:

Sir Joshua Reynolds was on very many accounts one of the most memorable men of his Time. He was the first Englishman who added the praise of the eligant Arts to the other Glories of his Country. In Taste, in grace, in facility, in happy invention, and in the richness and Harmony of colouring, he was equal to the great masters of the renowned Ages. In Pourtrait he went beyond them; for he communicated to that description of the art, in which English artists are the most engaged a variety, a Fancy, and a dignity derived from the higher Branches, which even those who professed them a superior manner, did not always preserve when they delineated individual nature. His Purtraits remind the Spectator of the Invention of History, and the amenity of Landscape. In painting pourtraits, he appeared not to be raised upon that platform; but to descend to it from an higher sphere. his paintings illustrate his Lessons — and his Lessons seem to be derived from his Paintings.

He possessed the Theory as perfectly as the Practice of his Art. To be such a painter, he was a profound and penetrating Philosopher.

In full affluence of foreign and domestick Fame, admired by the expert in art, and by the learned in Science, courted by the great, caressed by Sovereign powers, and celebrated by distinguished Poets, his Native humility, modesty and Candour never forsook him, even on surprise or provocation, nor was the least degree of arrogance or assumption visible to the most scrutinizing eye, in any part of his Conduct or discourse.

His talents of every kind powerful from Nature, and not meanly cultivated by Letters, his social Virtues in all the relations, and all the habitudes of Life renderd him the center of a very great and unparalleled Variety of agreeable Societies, which will be dissipated by his Death. He had too much merit not to excite some Jealously; too much innocence to provoke any Enmity. The loss of no man of his Time can be felt with more sincere, general, and unmixed Sorrow.

HAIL! AND FAREWELL!

Burke's tribute was well received and one journalist called it "the eulogium of Apelles pronounced by Pericles".

Reynolds was buried at St. Paul's Cathedral.

Professionally, Reynolds' career never peaked. He was one of the earliest members of the Royal Society of Arts, helped found the Society of Artists, and, with Gainsborough, established the Royal Academy of Arts as a spin off organization. In 1768 he was made the RA's first President, a position he held until his death. As a lecturer, Reynolds' Discourses on Art (delivered between 1769 and 1790) are remembered for their sensitivity and perception. In one of these lectures he was of the opinion that "invention, strictly speaking, is little more than a new combination of those images which have been previously gathered and deposited in the memory."

Reynolds and the Royal Academy have historically received a mixed reception. Critics include many of the Pre-Raphaelites, and William Blake, the latter having published his vitriolic Annotations to Sir Joshua Reynolds' Discourses in 1808. To the contrary, both J.M.W. Turner and James Northcote were fervent acolytes: Turner requested he be laid to rest at Reynolds' side, and Northcote (who lived for four years as Reynolds' pupil) wrote to his family "I know him thoroughly, and all his faults, I am sure, and yet almost worship him."

In appearance Reynolds was not striking. Slight, he was about 5'6" with dark brown curls, a florid complexion and features which James Boswell thought were "rather too largely and strongly limned." He had a broad face, a cleft chin, and the bridge of his nose was slightly dented; his skin was scarred by smallpox, and his upper lip disfigured as a result of falling from a horse as a young man. Edmond Malone asserted that "his appearance at first sight impressed the spectator with the idea of a well born and well bred English gentleman."

Renowned for his placidity, Reynolds often claimed that he "hated nobody". Never quite losing his Devonshire accent, he was not only an amiable and original conversationalist but a friendly and generous host, so that Fanny Burney recorded in her diary that he had "a suavity of disposition that set everybody at their ease in his society", and William Makepeace Thackeray believed "of all the polite men of that age, Joshua Reynolds was the finest gentleman." Dr. Johnson commented on the inoffensiveness of his nature; Edmund Burke noted his "strong turn for humor". Thomas Bernard, who later became Bishop of Killaloe, wrote in his verses on Reynolds:

"Dear knight of Plympton, teach me how

To suffer, with unruffled brow

And smile serene, like thine,

The jest uncouth or truth severe;

To such I'll turn my deafest ear

And calmly drink my wine.

Thou say'st not only skill is gained

But genius too may be attained

By studious imitation;

Thy temper mild, thy genius fine

I'll copy till I make them mine

By constant application."

Admittedly, some did construe Reynolds' equable calm as cool and unfeeling. Hester Lynch Piozzi's pen portrait reads:

"Of Reynolds what good shall be said?- or what harm?

His temper too frigid; his pencil too warm;

A rage for sublimity ill understood,

To seek still for the great, by forsaking the good..."

It is to this lukewarm temperament that Frederick W. Hilles, Bodman Professor of English Literature at Yale attributes the fact Reynolds never married. In the editorial notes of his compendium Portraits by Sir Joshua Reynolds, Hilles theorizes that "as a corollary one might say that he [Reynolds] was somewhat lacking in a capacity for love", and cites Boswell's notary papers: "He said the reason he would never marry was that every woman whom he liked had grown indifferent to him, and he had been glad he did not marry her." Reynolds' own sister, Frances, who lived with him as housekeeper, took her own negative opinion further still, thinking him "a gloomy tyrant". The presence of family compensated Reynolds for the absence of a wife; he wrote on one occasion to his friend Bennet Langton, that both his sister and niece were away from home "so that I am quite a bachelor." Biographer Ian McIntyre discusses the possibility of Reynolds having enjoyed sexual rendezvous with certain clients, such as Nelly O'Brien (or "My Lady O'Brien", as he playfully dubbed her) and Kitty Fisher, who visited his house for more sittings than were strictly necessary. Claims to this end are, however, purely speculative.