<Back to Index>

This page is sponsored by:

PAGE SPONSOR

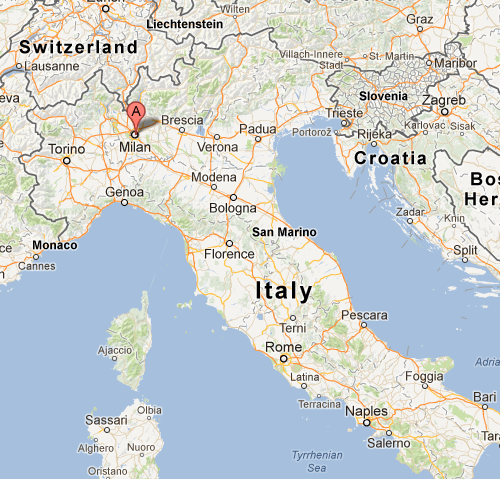

Milan (Italian: Milano; Lombard: Milan; German: Mailand; Latin: Mediolanum) is the second largest city in Italy and the capital of Lombardy. The city proper has a population of about 1.35 million, while its urban area is the 5th largest in the EU and the largest in Italy with an estimated population of about 5.2 million. The massive suburban sprawl that followed the Italian economic miracle of 1950s – 60s and the growth of a vast commuter belt, suggest that socioeconomic linkages have expanded well beyond the boundaries of its administrative limits and its agglomeration, creating a metropolitan area of 7-9 million people. It has been suggested that the Milan metropolitan area is part of the so-called Blue Banana, the area of Europe with the highest population and industrial density.

Milan was founded by the Insubres, a Celtic people. The city was later conquered by the Romans, becoming the capital of the Western Roman Empire. During the Middle Ages, Milan flourished as a commercial and banking center. In the course of centuries, it has been alternatively dominated by the Spanish, the Austrians and the French, until when in 1859 the city was eventually annexed by the new Kingdom of Italy. During the early 1900s, Milan led the industrialization process of the young nation, being at the very center of the economic, social and political debate. Badly affected by the World War II devastation, and after a harsh Nazi occupation, the city became the main center of the Italian resistance. In post - war years, the city enjoyed a prolonged economic boom, attracting large flows of immigrants from rural Southern Italy. During the last decades, Milan has seen a dramatic rise in the number of international migrants, and today more than one sixth of its population is foreign born.

Milan is the main industrial, commercial and financial center of Italy and a leading global city. Its business district hosts the Italian Stock Exchange and the headquarters of the largest national banks and companies. The city is a major world fashion and design capital. Thanks to its important museums, theaters and landmarks (including the Milan Cathedral, the fourth largest cathedral in the world, and Santa Maria delle Grazie, decorated with Leonardo da Vinci paintings (a UNESCO World Heritage Site), Milan attracts more than two million annual visitors. It hosts numerous cultural institutions and universities, including Bocconi University, which ranks fifth among European Business Schools. The city is also well known for several international events and fairs, including Milan Fashion Week and the Milan Furniture Fair, the largest of its kind in the world, and hosted the 2015 Universal Exposition. Milan is home to two world's major football teams, A.C. Milan and F.C. Internazionale Milano.

The etymology of Milan is uncertain. While the modern name of the city is clearly derived from its Latin name Mediolanum (from the Latin words medio, meaning "in the middle", and lanus, "plain"), it has been suggested that its original roots could lie more deeply in the city's Celtic heritage. Indeed, the name "Mediolanum" is borne by about sixty Gallo - Roman sites all over France, such as Saintes (Mediolanum Santonum) and Évreux (Mediolanum Aulercorum), as every Celtic community had its sacred assembly place of law and justice, usually placed at the midpoint of their territory. In addition, some scholars have suggested that the second element of the Latin name, lanum, could be identified with the Celtic root lan, signifying an enclosure or demarcated territory (source of the Welsh word 'llan', meaning a sanctuary or church) in which Celtic communities used to build shrines. Hence, Mediolanum could signify the central town or sanctuary of a particular Celtic tribe.

Another theory links the origin of the name to the boar sow (the Scrofa semilanuta) an ancient emblem of the city, fancifully accounted for in Andrea Alciato's Emblemata (1584), beneath a woodcut of the first raising of the city walls, where a boar is seen lifted from the excavation, and the etymology of Mediolanum given as "half - wool", explained in Latin and in French. The foundation of Milan is credited to two Celtic peoples, the Bituriges and the Aedui, having as their emblems a ram and a boar; therefore "The city's symbol is a wool - bearing boar, an animal of double form, here with sharp bristles, there with sleek wool." Alciato credits Ambrose for his account.

Around 400 BC, the Celtic Insubres settled Milan and the surrounding region. In 222 BC, the Romans conquered the settlement, which was then renamed Mediolanum. After several centuries of Roman control, Milan was declared the capital of the Western Roman Empire by Emperor Diocletian in 286 AD. Diocletian chose to stay in the Eastern Roman Empire (capital Nicomedia) and his colleague Maximianus ruled the Western one. Immediately Maximian built several gigantic monuments, like a large circus 470 m × 85 m (1,540 ft × 279 ft), the Thermae Herculeae, a large complex of imperial palaces and several other services and buildings.

With the Edict of Milan of 313, Emperor Constantine I guaranteed freedom of religion for Christians. The city was besieged by the Visigoths in 402, so the imperial residence was moved to Ravenna. In 452, the Huns overran the city. In 539, the Ostrogoths conquered and destroyed Milan in the course of the Gothic War against Byzantine Emperor Justinian I. In the summer of 569, the Lombards (from which the name of the Italian region Lombardy derives), a Teutonic tribe conquered Milan, overpowering the small Byzantine army left for its defense. Some Roman structures remained in use in Milan under Lombard rule. Milan surrendered to the Franks in 774 when Charlemagne, in an utterly novel decision, took the title "King of the Lombards" as well (before then the Germanic kingdoms had frequently conquered each other, but none had adopted the title of King of another people). The Iron Crown of Lombardy dates from this period. Subsequently Milan became part of the Holy Roman Empire.

During the Middle Ages, Milan prospered as a center of trade due to its command of the rich plain of the Po and routes from Italy across the Alps. The war of conquest by Frederick I Barbarossa against the Lombard cities brought the destruction of much of Milan in 1162. After the founding of the Lombard League in 1167, Milan took the leading role in this alliance. As a result of the independence that the Lombard cities gained in the Peace of Constance in 1183, Milan became a duchy. In 1208 Rambertino Buvalelli served a term as podestà of the city, in 1242 Luca Grimaldi, and in 1282 Luchetto Gattilusio. The position could be fraught with personal dangers in the violent political life of the medieval commune: in 1252 Milanese heretics assassinated the Church's Inquisitor, later known as Saint Peter Martyr, at a ford in the nearby contado; the killers bribed their way to freedom, and in the ensuing riot the podestà was very nearly lynched. In 1256 the archbishop and leading nobles were expelled from the city. In 1259 Martino della Torre was elected Capitano del Popolo by members of the guilds; he took the city by force, expelled his enemies, and ruled by dictatorial powers, paving streets, digging canals, successfully taxing the countryside. His policy, however, brought the Milanese treasury to collapse; the use of often reckless mercenary units further angered the population, granting an increasing support for the Della Torre's traditional enemies, the Visconti. It is worthy of note that the most important industries throughout the period were major armaments and wool production, a whole catalogue of activities and trades is given in Bonvesin della Riva's "de Magnalibus Urbis Mediolani".

On 22 July 1262 Ottone Visconti was created archbishop of Milan by Pope Urban IV, against the Della Torre candidate, Raimondo della Torre, Bishop of Como. The latter thus started to publicize allegations of the Visconti's closeness to the heretic Cathars and charged them of high treason: the Visconti, who accused the Della Torre of the same crimes, were then banned from Milan and their properties confiscated. The ensuing civil war caused more damage to Milan's population and economy, lasting for more than a decade. Ottone Visconti unsuccessfully led a group of exiles against the city in 1263, but after years of escalating violence on all sides, finally, after the victory in the Battle of Desio (1277), he won the city for his family. The Visconti succeeded in ousting the della Torre forever, ruling the city and its possession until the 15th century.

Much of the prior history of Milan was the tale of the struggle between two political factions: the Guelphs and the Ghibellines. Most of the time the Guelphs were successful in the city of Milan. However, the Visconti family were able to seize power (signoria) in Milan, based on their "Ghibelline" friendship with the German Emperors. In 1395, one of these emperors, Wenceslas (1378 – 1400), raised the Milanese to the dignity of a duchy. Also in 1395, Gian Galeazzo Visconti became duke of Milan. The Ghibelline Visconti family was to retain power in Milan for a century and a half from the early 14th century until the middle of the 15th century.

In 1447 Filippo Maria Visconti, Duke of Milan, died without a male heir; following the end of the Visconti line, the Ambrosian Republic was enacted. The Ambrosian Republic took its name from St. Ambrose, popular patron saint of the city of Milan. Both the Guelph and the Ghibelline factions worked together to bring about the Ambrosian Republic in Milan. However, the Republic collapsed when in 1450, Milan was conquered by Francesco Sforza, of the House of Sforza, which made Milan one of the leading cities of the Italian Renaissance.

The French king Charles VIII first laid claim to the duchy in 1492. At that time, Milan was defended by Swiss mercenaries. After the victory of Louis's successor François I over the Swiss at the Battle of Marignan, the duchy was promised to the French king François I. When the Habsburg Charles V defeated François I at the Battle of Pavia in 1525, northern Italy, including Milan, passed to the House of Habsburg.

In 1556, Charles V abdicated in favor of his son Philip II and his brother Ferdinand I. Charles's Italian possessions, including Milan, passed to Philip II and the Spanish line of Habsburgs, while Ferdinand's Austrian line of Habsburgs ruled the Holy Roman Empire. The Great Plague of Milan in 1629 – 31 killed an estimated 60,000 people out of a population of 130,000. This episode is considered one of the last outbreaks of the centuries - long pandemic of plague that began with the Black Death.

In 1700 the Spanish line of Habsburgs was extinguished with the death of Charles II. After his death, the War of the Spanish Succession began in 1701 with the occupation of all Spanish possessions by French troops backing the claim of the French Philippe of Anjou to the Spanish throne. In 1706, the French were defeated in Ramillies and Turin and were forced to yield northern Italy to the Austrian Habsburgs. In 1713, the Treaty of Utrecht formally confirmed Austrian sovereignty over most of Spain's Italian possessions including Lombardy and its capital, Milan.

Napoleon invaded Italy in 1796, and Milan was declared capital of the Cisalpine Republic. Later, he declared Milan capital of the Kingdom of Italy and was crowned in the Duomo. Once Napoleon's occupation ended, the Congress of Vienna returned Lombardy, and Milan, along with Veneto, to Austrian control in 1815. During this period, Milan became a center of lyric opera. Here in the 1770s Mozart had premiered three operas at the Teatro Regio Ducal. Later La Scala became the reference theater in the world, with its premières of Bellini, Donizetti, Rossini and Verdi. Verdi himself is interred in the Casa di Riposo per Musicisti, his present to Milan. In the 19th century other important theaters were La Cannobiana and the Teatro Carcano.

On 18 March 1848, the Milanese rebelled against Austrian rule, during the so-called "Five Days" (Italian: Le Cinque Giornate), and Field Marshal Radetzky was forced to withdraw from the city temporarily. However, after defeating Italian forces at Custoza on 24 July, Radetzky was able to reassert Austrian control over Milan and northern Italy. However, Italian nationalists, championed by the Kingdom of Sardinia, called for the removal of Austria in the interest of Italian unification. Sardinia and France formed an alliance and defeated Austria at the Battle of Solferino in 1859. Following this battle, Milan and the rest of Lombardy were incorporated into the Kingdom of Sardinia, which soon gained control of most of Italy and in 1861 was rechristened as the Kingdom of Italy.

The political unification of Italy cemented Milan's commercial dominance over northern Italy. It also led to a flurry of railway construction that had started under Austrian patrronage (Venice – Milan; Milan – Monza) that made Milan the rail hub of northern Italy. Thereafter with the opening of the Gotthard (1881) and Simplon (1906) railway tunnels, Milan became the major South European rail focus for business and passenger movements e.g. the Simplon Orient Express. Rapid industrialization and market expansion put Milan at the center of Italy's leading industrial region, though in the 1890s Milan was shaken by the Bava - Beccaris massacre, a riot related to a high inflation rate. Meanwhile, as Milanese banks dominated Italy's financial sphere, the city became the country's leading financial center.

In 1919, Fascist leader Benito Mussolini organized his Blackshirts in Milan, that rallied for the first time in Piazza San Sepolcro, a small square near Milan Cathedral. Subsequently, Mussolini led his March on Rome starting from the city. During the Second World War Milan suffered extensive damage from Allied bombings. When Italy quit the war in 1943, German forces occupied most of Northern Italy until 1945. As a result, antifascist resistance groups formed and started guerilla warfare against Nazi and Italian Social Republic's troops. As the war came to an end, the American 1st Armored Division advanced on Milan as part of the Po Valley Campaign. But before they arrived, members of the resistance seized control of the city and executed Mussolini along with several members of his collaborationist government. On 29 April 1945, the corpses of Mussolini, his mistress Clara Petacci and other Fascist leaders were infamously hanged in Piazzale Loreto, where a year before fifteen partisans had been executed.

During the post war economic miracle, a large wave of internal migration (especially from rural areas of Southern Italy), moved to the city, bringing the population from 1.3 million in 1951 to 1.7 million in 1967. During this period, Milan saw a quick reconstruction of most of its destroyed facilities, with the building of several innovative and modernist skyscrapers, such as the Torre Velasca and the Pirelli Tower, that soon became symbols of the boom. The economic prosperity was however overshadowed in the late 1960s and early 1970s during the so-called Years of Lead, when Milan witnessed an unprecedented wave of street violence, labor strikes and political terrorism. The apex of this period of turmoil occurred on 12 December 1969, when a bomb exploded at the National Agrarian Bank in Piazza Fontana, killing seventeen people and injuring eighty-eight.

In the 1980s, as several fashion firms based in the city became internationally successful (such as Armani, Versace and Dolce & Gabbana), Milan became one of the world's fashion capitals. The city saw also a marked rise in international tourism, notably from America and Japan, while the stock exchange increased its market capitalization more than five-fold. This short - lived period of collective euphoria and the new international image of the city led the mass media to nickname the metropolis "Milano da bere", literally "Milan to drink". However, in the 1990s, Milan was badly affected by Tangentopoli, a large political scandal in which many local and national politicians and businessmen were tried for alleged corruption. The city was also affected by a severe financial crisis and a steady decline in textiles, automobile and steel production, that led to a deep reorganization of its economy.

In the early 21st century, Milan underwent a series of massive redevelopments, with the moving of its exhibition centers to a much larger site in the satellite town of Rho, and the construction of a new financial district in Porta Nuova. Despite the decline in Milan's manufacturing production, the city has found alternative and successful sources of revenue, including publishing, finance, banking, food processing, information technology, logistics, transport and tourism. The 2010 official announcement of Milan hosting Expo 2015 brightened prospects for the city's future, with several new plans of regeneration and the planned construction of numerous futuristic structures. In addition, the city's decades - long population decline seems to have come to an end in recent years, with signs of recovery as it grew by seven percent since the last census.

Modern Milan has a central area focused on residential and tertiary activities, with a financial district that hosts the stock exchange and the headquarters of banks and insurance companies, shopping centers and educational institutions. In the concentric layout of the city center is still evident the influence of Navigli, an ancient system of navigable and interconnected canals, now mostly covered. Around the city proper, and beyond its railway and motorway rings, lies a vast urbanized valley that expands mainly to the north, engulfing many communes in a continuous urban landscape. The contiguous built-up area trespass by far the city limits, forming a vast urban agglomeration that stretches to the residential satellite towns of Rho, Bollate, Cinisello, Sesto San Giovanni and Monza and reaching the industrial centers of Busto Arsizio, Lecco, Desio and Dalmine.

There are few remains of the ancient Roman colony that later became a capital of the Western Roman Empire. During the second half of the fourth century, Saint Ambrose, as bishop of Milan, had a strong influence on the layout of the city, redesigning the center (although the cathedral and baptistery built at this time are now lost) and building the great basilicas at the city gates: Sant' Ambrogio, San Nazaro in Brolo, San Simpliciano and Sant' Eustorgio, which still stand, refurbished over the centuries, as some of the finest and most important churches in Milan. The largest and most important example of Gothic architecture in Italy, Milan's Cathedral, is the fourth largest in the world after St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, the Cathedral of Seville and a new cathedral in Côte d'Ivoire. Built between 1386 and 1577, it hosts the world's largest collection of marble statues and has a widely visible golden Madonna statue on top of the spire, nicknamed by the people of Milan as Madunina (the little Madonna), that became one of the symbols of the city.

In the second half of the fifteenth century, when the Sforza ruled the city, the old Visconti fortress was enlarged and embellished to became the Castello Sforzesco: the seat of an elegant Renaissance court surrounded by a walled hunting park stocked with game captured around the Seprio and Lake Como. Notable architects involved in the project included the Florentine Filarete, who was commissioned to build the high central entrance tower, and the military specialist Bartolomeo Gadio. The political alliance between Francesco Sforza and the Florence of Cosimo de' Medici bore architectural fruit, as Milanese building came under the influence of Brunelleschian models of Renaissance architecture. The first notable buildings to show this Tuscan influence were a palazzo built to house the Medici Bank (of which only the main entrance survives) and the centrally planned Portinari Chapel, attached to Sant’ Eustorgio and built for the first manager of the bank's Milan branch. Filarete, while in Milan, was responsible for the great public hospital known as the Ospedale Maggiore, and also for an influential Treatise on Architecture, which included a plan for a star shaped ideal city called Sforzinda in honor of Francesco Sforza and passionately argued for the centrally planned form.

Leonardo da Vinci, who was in Milan from around 1482 until the fall of the city to the French in 1499, was commissioned in 1487 to design a tiburio, or crossing tower for the cathedral, although he was not chosen to build it. However, the enthusiasm he shared with Filarete for the centrally planned building gave rise in this period to numerous architectural drawings, which were influential in the work of Donato Bramante and others. Bramante's work in the city, which included Santa Maria presso San Satiro (a reconstruction of a small 9th century church), the beautiful luminous tribune of Santa Maria delle Grazie and three cloisters for Sant' Ambrogio, drew also on his studies of the Early Christian architecture of Milan such as the Basilica of San Lorenzo.

The Counter - Reformation was also the period of Spanish domination and was marked by two powerful figures: Saint Charles Borromeo and his cousin, Cardinal Federico Borromeo. Not only did they impose themselves as moral guides to the people of Milan, but they also gave a great impulse to culture, with the creation of the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, in a building designed by Francesco Maria Ricchino, and the nearby Pinacoteca Ambrosiana. Many notable churches and Baroque mansions were built in the city during this period by the architects Pellegrino Tibaldi, Galeazzo Alessi and Ricchino himself.

Empress Maria Theresa of Austria was responsible for the significant renovations carried out in Milan during the 18th century. She instigated profound social and civil reforms, as well as the construction of many of the buildings that still today constitute the pride of the city, like the Teatro alla Scala, inaugurated on 3 August 1778 and today one of the world's most famous opera houses. The annexed Museo Teatrale alla Scala contains a collection of paintings, drafts, statues, costumes, and other documents regarding opera and La Scala's history. La Scala also hosts the Ballet School of the Teatro alla Scala. The Austrian sovereign also promoted culture in Milan through projects such as converting the ancient Jesuit College, in the district of Brera, into a scientific and cultural center with a Library, an astronomic observatory and the botanical gardens, in which the Art Gallery and the Academy of Fine Arts are today placed side by side. Milan was also widely affected by the Neoclassical movement in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, transforming its architectural style.

French Imperial rule of the city in the early 19th century produced several fine Neoclassical structures and mansions, Many of these are located in the Corso Venezia district, including Villa Reale or Villa del Belgiojoso, built by Leopoldo Pollack in 1790. It housed the Bonaparte family, mainly Joséphine Bonaparte, but also several others key political figures of 1800, such as Count Joseph Radetzky von Radetz and Eugène de Beauharnais. It is often regarded as one of the best types of Neoclassical architecture in Milan and Lombardy, surrounded by an English landscape garden. Today, it hosts a Gallery Contemporary Art in a fine context of classical columns, vast halls, marble statues and crystal chandeliers.

Additionally, major examples of Neoclassical architecture in the city include Palazzo Belgiojoso, former grand Napoleonic residence, and Palazzo Tarsis, built by Luigi Clerichetti for Count Paolo Tarsis in 1834, famous for its ornate façade. The massive Arch of Peace, also known as Porta Sempione (Sempione Gate), is situated in Piazza Sempione right at the end of the homonymous park. It is often compared to a miniature version of the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. The works began in 1806 by order of Napoleone Bonaparte, under supervision of architect Luigi Cagnola. Just like with the Arc de Triomphe, Napoleon's 1815 defeat at the Battle of Waterloo, halted the construction of the monumental arch, but Emperor Franz Josef I of Austria ordered it to be completed as a celebration of the Vienna Congress and the peace treaties of 1815. It was completed by Francesco Peverelli on 10 September 1838. Another noted Neoclassical building in the city is the Palazzo del Governo, constructed in 1817 by Piero Gilardoni.

In the second half of the 19th century, Milan quickly became the main industrial center in Italy, drawing inspiration from the great European capitals that were hubs of the technological innovations of the second industrial revolution and, consequently, of the deep social change that had been put in motion. The great Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, a covered passage that connects Piazza del Duomo, Milan to the square opposite of La Scala opera house, was built by architect Giuseppe Mengoni between 1865 and 1877 to celebrate Vittorio Emanuele II, first king of reunited Italy. The galleria is covered by an arching glass and cast iron roof, a popular design for 19th century arcades, such as the Burlington Arcade in London, which was the prototype for larger glazed shopping arcades, beginning with the Saint - Hubert Gallery in Brussels and the Passazh in St Petersburg. Another late 19th century eclectic monument in the city is Cimitero Monumentale, built in a Neo-Romanesque style by several architects between 1863 and 1866.

The tumultuous period of early 20th century brought several, radical innovations in Milanese architecture. Art Nouveau, also known as Liberty in Italy, started to develop in the city during the years before the Great War; alongside other major Italian cities, most notably Palermo and Turin, this particular style became highly popular, producing several notable buildings in the city, developing its own, individual style known as "Liberty Milanese" (Milanese Art Nouveau), which, in many aspects, shares many traits with Vienna Secession. Possibly one of the most notable Art Nouveau edifices in Milan is Palazzo Castiglioni in Corso Venezia, built by architect Giuseppe Sommaruga between 1901 and 1904. Other remarkable examples include Hotel Corso and Berri - Meregalli house, the latter built in a traditional Milanese Art Nouveau style combined with elements of neo - Romanesque and Gothic revival architecture, regarded as one of the last such types of architecture in the city. In 1906, with the Universal Exposition, the city was able to exhibit its Art Nouveau works, that was thus considered the official style of the exposition.

Nonetheless, as the century progressed, other styles started to be explored, including neo - Romanesque, eclectic and Gothic revival architecture, so Art Nouveau started falling out of fashion by c. 1913, when the official season was closed by Sommaruga. A new, more eclectic form of architecture can be seen in buildings such as Castello Cova, built the 1910s in a distinctly neo - medieval style, evoking the architectural trends of the past. A late Example of Art Deco, which blended such styles with Fascist architecture, is the massive Milano Centrale railway station by Ulisse Stacchini, inaugurated in 1931.

The post World War II period saw rapid reconstruction and fast economic growth, accompanied by a nearly twofold increase in population. A strong demand for new residential and commercial areas drove to extreme urban expansion and architectural renewal, that has produced some of the major milestones in the city's architectural history, including Gio Ponti's Pirelli Tower (1956 – 60), Velasca Tower (1956 – 58), and the creation of brand new residential satellite towns, as well as huge amounts of low quality public housings.

In recent years, de-industrialization, urban decay and gentrification led to a massive urban renewal of former industrial areas, that have been transformed into modern residential and financial districts, notably Porta Nuova and FieraMilano in the suburb of Rho. The old Fiera area is being completely rebuilt thanks to the project Citylife and will feature, among residences, museums and a large park, three skyscraper designed by famous international architects, from whom they will take the names: Isozaki Tower, Hadid Tower and Libeskind Tower. They will all have remarkable shapes: the Hadid Tower is twisted, the Libeskind Tower and the Isozaki Tower, although being perfectly straight, will reach 200m becoming the tallest building in Italy.

Milan boasts a wide variety of parks and gardens. The first public parks were established 1857 and 1862, and were designed by Giuseppe Balzaretto. They were situated in a "green park district", found in the areas of Piazzale Oberdan (Porta Venezia), Corso Venezia, Via Palestro and Via Manin. Most of them were landscaped in a Neoclassical style and represented traditional English gardens, often full of botanic richness. Since 1990 Milan is surrounded by the regional Parco Agricolo Sud Milano that wraps the southern half of the city, connecting Ticino Park in the west and Adda Park in the east. The Park was instituted in order to safeguard and enhance the old agricultural landscape and activities, woodlands and natural reserves, with an overall size of 47,000 hectares.

The most important parks in Milan are the set of adjacent parks in the western area of the city, forming Parco Agricolo Sud Milano (Parco delle Cave, 131 hectares; Boscoincittà, 110 hectares; and Trenno Park, 59 hectares, whose total area amounts to about 300 hectares), Sempione Park, Parco Forlanini, Giardini Pubblici, Giardino della Villa Comunale, Giardini della Guastalla and Lambro Park. Sempione Park is a large public park, situated between the Castello Sforzesco and the Peace Arch, near Piazza Sempione. It was built by Emilio Alemagna, and contains a Napoleonic Arena, the Milan City Aquarium, a tower, an art exhibition center, some ponds and a library. Then there is Parco Forlani, which, with a size of 235 hectares, is the largest park in Milan, and contains a hill and a pond. Giardini Pubblici is among Milan's oldest remaining public parks, founded on 29 November 1783, and completed around 1790. It is landscaped in English style, containing a pond, a Natural History Museum of Milan and the Neoclassical Villa Reale. Giardini della Guastalla is also one of the oldest gardens in Milan, and consists mainly of a decorated fish pond.

Milan also hosts three important botanical gardens: the Milan University Experimental Botanical Garden (a small botanical garden operated by the Istituto di Scienze Botaniche), the Brera Botanical Garden (another botanical garden, founded in 1774 by Fulgenzio Witman, an abbot under the orders of Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, and restored in 1998 after several years of abandonment) and the Cascina Rosa Botanical Garden. On 23 January 2003, a Garden of the Righteous was established in Monte Stella to commemorate those who opposed genocides and crimes against humankind. It hosts trees dedicated to Moshe Bejski, Andrei Sakharov, the founders of the Gardens of the Righteous in Yerevan and Pietro Kuciukian, and others.

The city contains several cultural institutions, museums and galleries, some of which are highly important at an international level, such as the city's Duomo and Piazza, the Convent of Sta. Maria delle Grazie with Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper, the San Siro Stadium, the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, the Castello Sforzesco, the Pinacoteca di Brera and the Via Monte Napoleone. Most tourists visit sights such as Milan Cathedral, the Castello Sforzesco and the Teatro alla Scala, however, other main sights such as the Basilica of Sant' Ambrogio, the Navigli and the Brera Academy and district are less visited and prove to be less popular.

The Pinacoteca di Brera is one of Milan's most important art galleries. It contains one of the foremost collections of Italian paintings, an outgrowth of the cultural program of the Brera Academy, which shares the site in the Brera Academy. It contains masterpieces such as the Brera Madonna by Piero della Francesca. The Castello Sforzesco hosts numerous art collections and exhibitions. The best known of the current civic museums is the Pinacoteca del Castello Sforzesco, with an art collection including Michelangelo's last sculpture, the Rondanini Pietà, Andrea Mantegna's Trivulzio Madonna and Leonardo da Vinci's Codex Trivulzianus manuscript. The Castello complex also includes The Museum of Ancient Art, The Furniture Museum, The Museum of Musical Instruments and the Applied Arts Collection, The Egyptian and Prehistoric sections of the Archaeological Museum and the Achille Bertarelli Print Collection.

Milan's figurative art flourished in the Middle Ages, and with the Visconti family being major patrons of the arts, the city became an important center of Gothic art and architecture (Milan Cathedral being the city's most formidable work of Gothic architecture). Also, rule of the Sforza family, between the 14th and 15th century, was another period in which art and architecture flourished. Milan became the seat of an elegant Renaissance court, while great works, such as the Ospedale Maggiore, the public hospital designed by Filarete were built, and artists of the caliber of Leonardo da Vinci came to work in Milan, leaving works of inestimable value, such as the fresco of the Last Supper and the Codex Atlanticus.

Bramante also came to Milan to work on the construction of some of the most beautiful churches in the city; in Santa Maria delle Grazie the beautiful luminous tribune is by Bramante, as is the church of Santa Maria presso San Satiro.

The city was affected by the Baroque in the 17th and 18th centuries, and hosted numerous formidable artists, architects and painters of that period, such as Caravaggio and Francesco Hayez, which several important works are hosted in Brera Academy.

Milan in the 20th century was the epicenter of the Futurist artistic movement. Filippo Marinetti, the founder of Italian Futurism wrote in his 1909 "Futurist Manifesto" (in Italian, Manifesto Futuristico), that Milan was "grande... tradizionale e futurista" ("grand... traditional and futuristic"). Umberto Boccioni was also an important Futurism artist who worked in the city. Today, Milan remains a major international hub of modern and contemporary art, with numerous modern exhibitions. The Museum of Twentieth Century, sited in the Arengario palace near Duomo square in the centre of Milan, is one of the most important art galleries about Italian and international Twentieth Century’s art in Italy: of particular relevance are the sections dedicated to Futurism, Spatialism and Arte povera.

The Museo Poldi Pezzoli is another of the city's most important and prestigious museums. The museum was originated in the 19th century as the private collection of Gian Giacomo Poldi Pezzoli and his mother, Rosa Trivulzio, of the family of the condottiero Gian Giacomo Trivulzio, and has a particularly broad collection of Northern Italian and (for Italy) Netherlandish / Flemish artists. The Museum of the Risorgimento (Museo del Risorgimento) is a museum in Milan on the history of Italian unification from 1796 (Napoleon's first Italian campaign) and 1870 (Rome's annexation into the Kingdom of Italy) and on Milan's part in it (particularly the Five Days of Milan). It is housed in the 18th century Palazzo Moriggia. Its collections include Baldassare Verazzi's Episode from the Five Days and Francesco Hayez's 1840 Portrait of Emperor Ferdinand I of Austria. La Triennale di Milano is a design museum and events venue located inside the Palace of Art building, part of Parco Sempione, the park grounds adjacent to Castello Sforzesco. It hosts exhibitions and events highlighting contemporary Italian design, urban planning, architecture, music, and media arts, emphasizing the relationship between art and industry.

Milan is regarded as one of the international capitals of industrial and modern design, and one of the world's most influential cities in such fields. The city is particularly well known for its high quality ancient and modern furniture and industrial goods. Milan hosts the FieraMilano, Europe's biggest, and one of the world's most prestigious furniture and design fairs. Milan also hosts major design and architecture related events and venues, such as the "Fuori Salone" and the Salone del Mobile. In the 1950s and 60s as well as early 70's, being the main industrial center of Italy and one of mainland Europe's most progressive and dynamic cities, Milan became, along with Turin, Italy's capital of post war design and architecture. Skyscrapers, such as the Pirelli Tower and the Torre Velasca were constructed, and artists such as Bruno Munari, Lucio Fontana, Enrico Castellani and Piero Manzoni, to name a few, either lived or worked in the city.

Milan is also regarded as one of the fashion capitals of the world, along with New York City, Paris, and London. The Global Language Monitor declared that in 2009 Milan was the top economic and media global capital of fashion, despite the fact it fell down to sixth place in 2010, and went up to fourth place in 2011. Most of the major Italian fashion brands, such as Valentino, Gucci, Versace, Prada, Armani and Dolce & Gabbana, are currently headquartered in the city. Numerous international fashion labels also operate shops in Milan, including an Abercrombie & Fitch flagship store, which has become a main consumer attraction. Furthermore, the city hosts the Milan Fashion Week twice a year, just like other international centers such as Paris, London, Tokyo, and New York. Milan's main upscale fashion district is the quadrilatero della moda (literally, "fashion quadrilateral"), where the city's most prestigious shopping streets (Via Monte Napoleone, Via della Spiga, Via Sant'Andrea, Via Manzoni and Corso Venezia) are located. The Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, the Piazza del Duomo, Via Dante and Corso Buenos Aires are other important shopping streets and squares. Mario Prada, founder of Prada was born here, helping to cultivate its position as a world fashion capital.

In the late 18th century, and throughout the 19th, Milan was an important centre for intellectual discussion and literary creativity. The Enlightenment found here a fertile ground. Cesare, Marquis of Beccaria, with his famous Dei delitti e delle pene, and Count Pietro Verri, with the periodical Il Caffè were able to exert a considerable influence over the new middle class culture, thanks also to an open minded Austrian administration. In the first years of the 19th century, the ideals of the Romantic movement made their impact on the cultural life of the city and its major writers debated the primacy of Classical versus Romantic poetry. Here, too, Giuseppe Parini, and Ugo Foscolo published their most important works, and were admired by younger poets as masters of ethics, as well as of literary craftsmanship. Foscolo's poem Dei sepolcri was inspired by a Napoleonic law that — against the will of many of its inhabitants — was being extended to the city. In the third decade of the 19th century, Alessandro Manzoni wrote his novel I Promessi Sposi, considered the manifesto of Italian Romanticism, which found in Milan its center, and Carlo Porta wrote his poems in Western Lombard Language. The periodical Il Conciliatore published articles by Silvio Pellico, Giovanni Berchet, Ludovico di Breme, who were both Romantic in poetry and patriotic in politics. After the Unification of Italy in 1861, Milan lost its political importance; nevertheless it retained a sort of central position in cultural debates. New ideas and movements from other countries of Europe were accepted and discussed: thus Realism and Naturalism gave birth to an Italian movement, Verismo. The greatest verista novelist, Giovanni Verga, was born in Sicily but wrote his most important books in Milan.

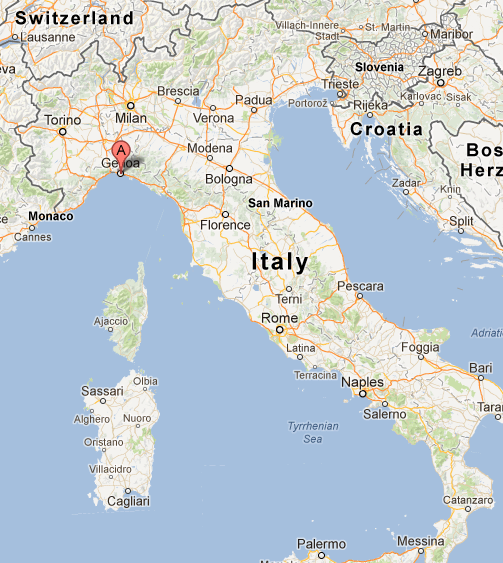

Genoa (Italian: Genova; Genoese and Ligurian Zena; Latin and, archaically, English Genua) is the capital of Liguria and the sixth largest city in Italy, with a population of 608,676 within its administrative limits on a land area of 243.6 km2 (94 sq mi). The urban zone of Genoa extends beyond the administrative city limits with a population of 718,896. The urban area of Genoa has a population of 800,709. In the metropolitan area live over 1.5 million people. Genoa is one of Europe's largest cities on the Mediterranean Sea and the largest seaport in Italy.

Genoa has been nicknamed la Superba ("the Superb one") due to its glorious past and impressive landmarks. Part of the old town of Genoa was inscribed on the World Heritage List (UNESCO) in 2006. The city's rich art, music, gastronomy, architecture and history, allowed it to become the 2004's European Capital of Culture. It is the birthplace of Christopher Columbus.

Genoa, which forms the southern corner of the Milan - Turin - Genoa industrial triangle of north - west Italy, is one of the country’s major economic centres. The city, since the 19th century, hosts massive shipyards, oil refineries and steelworks, while its solid financial sector dates back to the Middle Ages. The Bank of Saint George is among the oldest in the world, as it was founded in 1407, playing an important role in the city’s prosperity from the middle of the 15th century. Today a number of leading Italian companies are based in the city, including Fincantieri, Ansaldo Energia, Ansaldo STS and Edoardo Raffinerie Garrone.

Genua was a city of the ancient Ligurians. Its name may derive from the Latin word meaning "knee" (genu; plural, genua), i.e. "angle", from its geographical position at the centre of the Ligurian coastal arch, or it could derive from the Celtic root genu-, genawa (pl. genowe), meaning "mouth", i.e., estuary; thus akin to the name of Geneva.

The flag of Genoa is simply a St George's Cross, a red cross on a lime white field, identical to the Flag of England and incorporated into the Flag of Georgia. Some historians believe that the Flag of England derives from the flag of Genoa, which originates as far back as 1096. On the origins of the flag the Duke of Kent remarked:

"The St. George's flag, a red cross on a white field, was adopted by England and the City of London in 1190 for their ships entering the Mediterranean to benefit from the protection of the Genoese fleet. The English Monarch paid an annual tribute to the Doge of Genoa for this privilege."

HRH The Duke of Kent

Genoa's history goes back to ancient times. The first historically known inhabitants of the area are the Ligures.

A city cemetery, dating from the 6th and 5th centuries BC, testifies to the occupation of the site by the Greeks, but the fine harbor was probably in use much earlier, perhaps by the Etruscans. It is also probable that the Phoenicians had bases in Genoa, or in the nearby area, since an inscription with an alphabet similar to that used in Tyre has been found.

In the Roman era, Genoa was overshadowed by the powerful Marseille and Vada Sabatia, near modern Savona. Different from other Ligures and Celt settlements of the area, it was allied to Rome through a foedus aequum ("Equal pact") in the course of the Second Punic War. It was therefore destroyed by the Carthaginians in 209 BC. The town was rebuilt and, after the end of the Carthaginian Wars, received municipal rights. The original castrum thenceforth expanded towards the current areas of Santa Maria di Castello and the San Lorenzo promontory. Genoese trades included skins, wood, and honey. Goods were shipped to the mainland from Genoa, up to major cities like Tortona and Piacenza.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Genoa was occupied by the Ostrogoths. After the Gothic War, the Byzantines made it the seat of their vicar. When the Lombards invaded Italy in 568, the Bishop of Milan fled and held his seat in Genoa. Pope Gregory the Great was closely connected to these bishops in exile, for example involving himself in the election of Deusdedit. The Lombards, under King Rothari, finally captured Genoa and other Ligurian cities in about 643. In 773 the Lombard Kingdom was annexed by the Frank empire; the first Carolingian count of Genoa was Ademarus, who was given the title praefectus civitatis Genuensis. Ademarus died in Corsica while fighting against the Saracens. In this period the Roman walls, destroyed by the Lombards, were rebuilt and extended.

For the following several centuries, Genoa was little more than a small, obscure fishing centre, slowly building its merchant fleet which was to become the leading commercial carrier of the Mediterranean Sea. The town was sacked and burned in 934 by North African pirates and likely abandoned for a few years.

In the 10th century the city, now part of the Marca Januensis ("Genoese March") was under the Obertenghi family, whose first member was Obertus I. Genoa was one of the first cities in Italy to have some citizenship rights granted by local feudatories.

Before 1100, Genoa emerged as an independent city - state, one of a number of Italian city - states during this period. Nominally, the Holy Roman Emperor was overlord and the Bishop of Genoa was president of the city; however, actual power was wielded by a number of "consuls" annually elected by popular assembly. Genoa was one of the so-called "Maritime Republics" (Repubbliche Marinare), along with Venice, Pisa, and Amalfi and trade, shipbuilding and banking helped support one of the largest and most powerful navies in the Mediterranean. The Adorno, Campofregoso, and other smaller merchant families all fought for power in this Republic, as the power of the consuls allowed each family faction to gain wealth and power in the city. The Republic of Genoa extended over modern Liguria and Piedmont, Sardinia, Corsica, Nice and had practically complete control of the Tyrrhenian Sea. Through Genoese participation on the Crusades, colonies were established in the Middle East, in the Aegean, in Sicily and Northern Africa. Genoese Crusaders brought home a green glass goblet from the Levant, which Genoese long regarded as the Holy Grail. Not all of Genoa's merchandise was so innocuous, however, as medieval Genoa became a major player in the slave trade.

The collapse of the Crusader States was offset by Genoa’s alliance with the Byzantine Empire. As Venice's relations with the Byzantine Empire were temporarily disrupted by the Fourth Crusade and its aftermath, Genoa was able to improve its position. Genoa took advantage of this opportunity to expand into the Black Sea and Crimea. Internal feuds between the powerful families, the Grimaldi and Fieschi, the Doria, Spinola, and others caused much disruption, but in general the republic was run much as a business affair. In 1218 – 1220 Genoa was served by the Guelph podestà Rambertino Buvalelli, who probably introduced Occitan literature to the city, which was soon to boast such troubadours as Jacme Grils, Lanfranc Cigala, and Bonifaci Calvo. Genoa's political zenith came with its victory over the Republic of Pisa at the naval Battle of Meloria in 1284, and with a temporary victory over its rival, Venice, at the naval Battle of Curzola in 1298.

However, this prosperity did not last. The Black Death was imported into Europe in 1347 from the Genoese trading post at Caffa (Theodosia) in Crimea, on the Black Sea. Following the economic and population collapse, Genoa adopted the Venetian model of government, and was presided over by a doge. The wars with Venice continued, and the War of Chioggia (1378 – 1381) -- where Genoa almost managed to decisively subdue Venice — ended with Venice's recovery of dominance in the Adriatic. In 1390 Genoa initiated a crusade against the Barbary pirates with help of the French and laid siege to Mahdia. Though it has not been well studied, the fifteenth century seems to have been a tumultuous time for Genoa. After a period of French domination from 1394 – 1409, Genoa came under rule by the Visconti of Milan. Genoa lost Sardinia to Aragon, Corsica to internal revolt and its Middle Eastern, Eastern European and Asia Minor colonies to the Turkish Ottoman Empire.

Genoa was able to stabilize its position as it moved into the sixteenth century, particularly thanks to the efforts of Andrea Doria, who established a new constitution in 1528, making Genoa a satellite of the Spanish Empire. Under the ensuing economic recovery, many aristocratic Genoese families, such as the Balbi, Doria, Grimaldi, Pallavicini, and Serra, amassed tremendous fortunes. According to Felipe Fernandez - Armesto and others, the practices Genoa developed in the Mediterranean (such as chattel slavery) were crucial in the exploration and exploitation of the New World. Christopher Columbus, for example, was a native of Genoa and donated one - tenth of his income from the discovery of the Americas for Spain to the Bank of Saint George in Genoa for the relief of taxation on foods.

At the time of Genoa’s peak in the 16th century, the city attracted many artists, including Rubens, Caravaggio and Van Dyck. The famed architect Galeazzo Alessi (1512 – 1572) designed many of the city’s splendid palazzi, as did in the decades that followed by fifty years Bartolomeo Bianco (1590 – 1657), designer of centrepieces of University of Genoa. A number of Genoese Baroque and Rococo artists settled elsewhere and a number of local artists became prominent.

The plague killed as many as half of the inhabitants of Genoa in 1656 – 57.

In May 1625 the French - Savoian army that invaded the Republic was successfully driven out by the combined Spanish and Geonese armies. In May 1684, as a punishment for Genoese support for Spain, the city was subjected to a French naval bombardment, with some 13,000 cannonballs aimed at the city.

It was occupied by Austria in 1746 during the War of the Austrian Succession. This episode in the city's history is mainly remembered for the Genoese revolt, precipitated by a boy named Giovan Battista Perasso and nicknamed Balilla, who threw a stone at an Austrian official and became a national hero to later generations of Genoese (and Italians in general).

Being unable to retain its rule in Corsica, where the rebel Corsican Republic was proclaimed in 1755, in 1768 Genoa was forced by the endemic rebellion to sell its claim to Corsica to the French, in the Treaty of Versailles of 1768.

With the shift in world economy and trade routes to the New World and away from the Mediterranean, Genoa's political and economic power went into steady decline. In 1797, under pressure from Napoleon, Genoa became a French protectorate called the Ligurian Republic, which was annexed by France in 1805. This affair is commemorated in the famous first sentence of Tolstoy's War and Peace:

"Well, Prince, so Genoa and Lucca are now just family estates of the Buonapartes.(...) And what do you think of this latest comedy, the coronation at Milan, the comedy of the people of Genoa and Lucca laying their petitions [to be annexed to France] before Monsieur Buonaparte, and Monsieur Buonaparte sitting on a throne and granting the petitions of the nations?" (spoken by a thoroughly anti - Boanapartist Russian aristocrat, soon after the news reached Saint Petersburg).

Although the Genoese revolted against France in 1814 and liberated the city on their own, delegates at the Congress of Vienna sanctioned its incorporation into Piedmont (Kingdom of Sardinia), thus ending the three century old struggle by the House of Savoy to acquire the city.

The city soon gained a reputation as a hotbed of anti - Savoy republican agitation (having its climax in 1849 with the Sack of Genoa), although the union with Savoy was economically very beneficial. With the growth of the Risorgimento movement, the Genoese turned their struggles from Giuseppe Mazzini's vision of a local republic into a struggle for a unified Italy under a liberalized Savoy monarchy. In 1860, General Giuseppe Garibaldi set out from Genoa with over a thousand volunteers to begin the conquest of Southern Italy. Today a monument is set on the rock where the patriots departed from.

In the late 1800s and the early 1900s, Genoa consolidated its role as a major seaport and an important steel and shipbuilding center. During World War II Genoa suffered heavy damages. In a well known episode, the British fleet bombarded Genoa and one shell fell into the cathedral of San Lorenzo without exploding. It is now available to public viewing on the cathedral premises. The city was liberated by the partisans a few days before the arrival of the Allies.

In the post - war years, Genoa played a pivotal role in the Italian economic miracle, as the third corner of the so-called "Industrial Triangle" of northern Italy, formed by the manufacturer hubs of Milan and Turin and the seaport of Genoa itself. Since 1962, the Genoa International Boat Show has evolved as one of the largest annually recurring events in Genoa. The 27th G8 summit in the city, in July 2001, was overshadowed by violent protests, with one protester, Carlo Giuliani, killed amid accusations of police brutality. In 2007 15 officials, who included police, prison officials and two doctors, were found guilty by an Italian court of mistreating protesters. A judge handed down prison sentences ranging from five months to five years. In 2004, the European Union designated Genoa as the European Capital of Culture, along with the French city of Lille.

Genoa's historic centre is one of the widest of Europe (about 400.000 m2). The structure of its oldest part is articulated in a maze of squares and narrow caruggi (typical genoese alleys). It joins a medieval dimension with following 16th century and baroque interventions (San Matteo square and the ancient via Aurea, now via Garibaldi).

Remains of the ancient 17th century walls are still visible nearby San Lorenzo cathedral, the most attended place of worship of Genoa.

The symbols of the city are the Lanterna (the lighthouse) (117 m high), old and standing lighthouse visible in the distance from the sea (beyond 30 km), and the monumental fountain of Piazza De Ferrari, recently restored, out-and-out core of the city's life. Another par excellence tourist destination is the ancient seaside district of Boccadasse, with its picturesque multicolor boats, set as a seal to Corso Italia, the elegant promenade which runs along the Lido d'Albaro, and renowned for its famous ice creams.

Just out of the city centre, but still part of the 33 kilometres of coast included in the municipality's territory, are Nervi, natural doorway to the Ligurian East Riviera, and Pegli, the point of access to the West Riviera.

The new Genoa most of all based its rebirth upon the restoration of the green areas of the immediate inland parts (among them the Regional Natural Park of Beigua) and upon the realization of facilities such as the Acquario in the Old Harbour - the biggest in Italy and one of the major in Europe - and its Marina (the tourist small port which holds hundreds of pleasure boats). All of this inside the restored Expo Area, arranged in occasion of the Columbian Celebrations of 1992.

The regained pride gave back to the city the consciousness of being capable of looking to the future without forgetting its past. The resumption of several flourishing hand crafting activities, far back absent from the caruggi of the old town, is a direct evidence of it.

The restoration of many of Genoa's churches and palaces in the 80's and the 90's contributed to the city's rebirth. A notable example the Renaissance Basilica of Santa Maria Assunta, sitting on the top of the hill of Carignano and visible from almost every part of the city.

The total restoration of Palazzo Ducale - once venue of doges and senators and nowadays location of cultural events - and of the Old Harbor and the rebuilding of Teatro Carlo Felice, destroyed by the Second World War bombings that only spared the neoclassic pronao of the architect Carlo Barabino, were two more points of strength for the realization of a new Genoa.

Another monument of relevant importance that has been restored to its former beauty is the monumental Cemetery of Staglieno, in which the mortal remains of several known personalities rest, among them Giuseppe Mazzini, Fabrizio De André and Oscar Wilde's wife. With its characteristic skyline that still today gives the impression of an insurmountable fortress, it is distinguished by its thick network of hill fortifications on wide walls, that in the past war times mede the cemetery impregnable both for the ground and sea attacks. In recent decades Genoa has become a sort of capital of the Italian modern architecture, as well as European. This is principally owed to Renzo Piano's work, that since the end of the 1980s has been dealing with the restoration of some of the most famous cities of the world. Piano acquired notoriety as from 1992, when Genoa hosted visitors in its Old Harbor, in occasion of the Columbian Celebrations ("Colombiadi"). The waterfront was completely restored and symbolized by the stylized "Great Bigo" (a sort of trademark of the genoese portual activity). Beyond a complete restyling of the area, the ancient portal zone nearby the Mandraccio opening, in Porta Siberia, was scenographically enriched by Piano himself with a big sphere made of metal and glass, installed in the port's waters, not far from the Acquario, and unveiled in 2001 in occasion of the G8 Summit held in Genoa. The sphere (called by the citizens "Piano's bubble' or "the ball"'"), after hosting an exposition of fens from Genoa's Botanical Gardens, houses now the reconstruciton of a tropical environment, with several plants, little animals and butterflies. Piano also projected the subway's stations and, in the hills area, the construction - in collaboration with UNESCO - of Punta Nave, base of the "Renzo Piano Building Workshop".

Nearby the Old Harbor the so-called "Matitone" can be seen, especially by those who cross the city centre by way of the elevated road (the "Sopraelevata"), controversial as well as peculiar skyscraper in shape of a pencil, that lays side by side with the group of the WTC towers, core of the San Benigno development, today base of part of the Municipality's administration and of several companies.

St. Lawrence Cathedral (Cattedrale di San Lorenzo) is the city's Cathedral, and is built in a Romanesque - Renaissance style. Other important and major churches in Genoa include the Church of San Donato, the Church of Sant' Agostino, the Oratory of San Giacomo della Marina, the Church of Santo Stefano, San Torpete and the Basilica della Santissima Annunziata del Vastato. Most of these churches and basilicas are built in the Romanesque style, even though the Basilica della Santissima Annunziata del Vastato is built in a rich and elaborate Baroque style.

The main features of central Genoa include Piazza De Ferrari, around which are sited the Opera and the Palace of the Doges. There is also a house where Christopher Columbus is said to have been born.

Strada Nuova (now Via Garibaldi), in the old city, was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2006. This district was designed in the mid 16th century to accommodate Mannerist palaces of the city's most eminent families, including Palazzo Rosso (now a museum), Palazzo Bianco, Palazzo Grimaldi and Palazzo Reale. Palazzo Bianco and Palazzo Rosso are also known as Musei di Strada Nuova. The famous art college is also located on this street.

Other landmarks of the city include Palazzo del Principe, the Old Harbor (Porto Antico), transformed into a mall by architect Renzo Piano, and the famous cemetery of Staglieno, renowned for its monuments and statues. The Edoardo Chiossone Museum of Oriental Art has one of the largest collections of Oriental art in Europe.

The first organized forms of higher education in Genoa date back to the 13th century when private colleges were entitled to award degrees in Medicine, Philosophy, Theology, Law, Arts. Today the University of Genoa, founded in the 15th century, is one of the largest in Italy, with 11 faculties, 51 departments and 14 libraries. In 2007 – 2008, the University had 41,000 students and 6,540 graduates.

Genoa is also home to other colleges and academies:

- The Italian Shipping Academy

- The Ligurian Academy of Fine Arts

- The "Niccolò Paganini" Conservatory

- The Italian Hydrographic Institute

- The Grazia Deledda Academy and School

The Italian Institute of Technology was established in 2003 jointly by the Italian Ministry of Education, Universities and Research and the Italian Minister of Economy and Finance, to promote excellence in basic and applied research. The main fields of research of the Institute are Neuroscience, Robotics, Nanotechnology, Drug discovery. The central research labs and headquarters are located in Morego, in the neighbourhood of Bolzaneto.

Genoa has a rich artistic history, with numerous frescos, paintings, sculptures and other works of art held in the city's abundant museums, palaces, villas, art galleries and piazzas. Genoa is the birthplace and home of the 'Ligurian School', where the key figures were several native and foreign painters, such as Rubens, Van Dyck and Bernardo Strozzi.

Much of the city's art is found in its churches and palaces, where there are numerous Renaissance, Baroque and Rococo frescos, such as in the Genoa Cathedral, the Church of Gesù and the Church of San Donato.

Genoa is also famous for its numerous tapestries, which decorated the city's many salons. Whilst the patrician palaces and villas in the city were and still are austere and majestic, the interiors tended to be luxurious and elaborate, often full of tapestries, many of which were Flemish.

The Genoese dialect (Zeneize) is the most important dialect of the Ligurian language, and is commonly spoken in Genoa alongside Italian.

Ligurian is listed by Ethnologue as a language in its own right, of the Romance branch, and not to be confused with the ancient Ligurian language. Like the languages of Lombardy, Piedmont, and surrounding regions, it is of Gallo - Italic derivation.

The Teatro Carlo Felice, built in 1828 in the city in the Piazza De Ferrari, and named for the monarch of the then Kingdom of Sardinia (which included the present regions of Sardinia, Piedmont and Liguria). The theater was the centre of music and social life in the 19th century. On various occasions in the history of the theatre, presentations have been conducted by Mascagni, Richard Strauss, Hindemith and Stravinsky.

On the occasion of the Christopher Columbus celebration in 1992, new musical life was given to the area around the old port, including the restoration of the house of Paganini and presentations of the Trallalero, the traditional singing of Genoese dock workers. Additionally, the city is the site of the Teatro Gustavo Modena, the only theater to have survived the bombings of World War II relatively intact. The city is the site of the Niccolò Paganini music conservatory. In the town of Santa Margherita Ligure, the ancient Abbey of Cervara is often the site of chamber music concerts.

The city has also a tradition of folk music in Genoese dialect, like the trallalero (a polyphonic vocal music, performed by five men) and several songs, including the well known piece "Ma se ghe penso" (English: "But if I think about it"), a nostalgic memory of Genoa by an emigrant to Argentina.