<Back to Index>

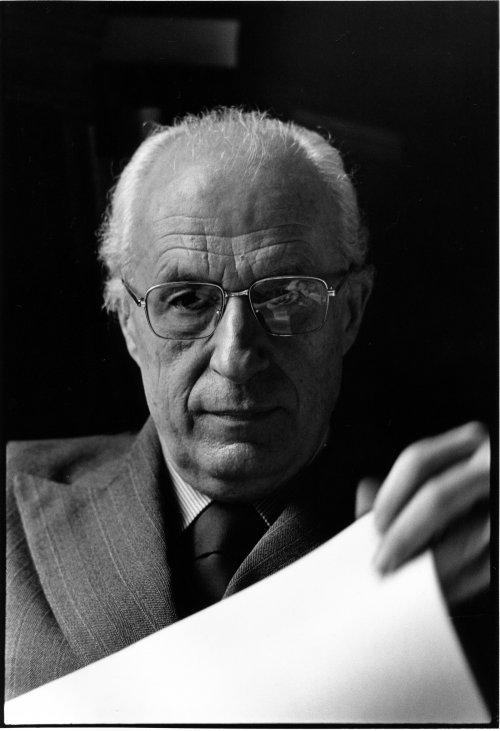

- Historian Philippe Ariès, 1914

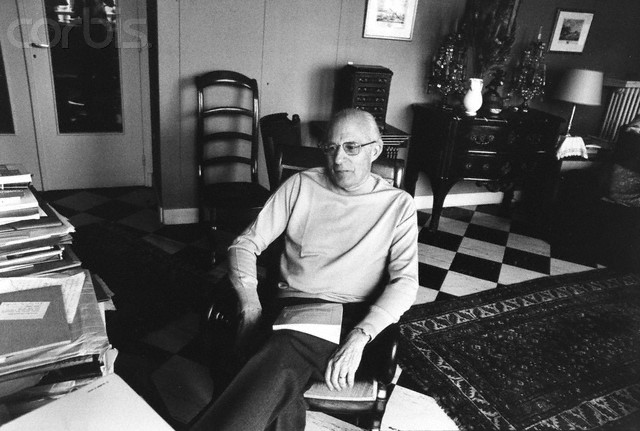

- Historian Roger Chartier, 1945

PAGE SPONSOR

Philippe Ariès (21 July 1914, Blois – 8 February 1984, Paris) was a French medievalist and historian of the family and childhood, in the style of Georges Duby. Ariès wrote many books on the common daily life. His most prominent works regarded the change in the western attitudes towards death.

Ariès regarded himself as a "right wing anarchist". He was initially close to the Action française, but with time distanced himself from it, viewing it as excessively authoritarian — hence his self description as an "anarchist". Ariès likewise contributed to La Nation française, a royalist review. However, he also cooperated with many left wing French historians and did so especially closely with Michel Foucault, who wrote his obituary.

Paradoxically, during Ariès' life, his work was often better known in the English speaking world than it was in France itself. He is known above all for his book L’Enfant et la Vie Familiale sous l’Ancien Régime (1960), which was translated into English as Centuries of Childhood (1962). This book stands preeminent in the history of childhood, as it was essentially the first book on the subject (although some antiquarian texts were in existence prior to this). Even today, Ariès remains the standard reference to the topic. Ariès is most famous for his statement that "in medieval society, the idea of childhood did not exist". The central thesis of Centuries of Childhood is that attitudes towards children were progressive, and evolved over time with economic change and social advancement, until childhood, as a concept and an accepted part of family life, came into being in the seventeenth century. It was thought that children were too weak to be counted and that they could disappear at any time. But these children were considered as an adult as soon as they could live without the help of their mothers, nanny, or someone else. Centuries of Childhood has had mixed fortunes. Ariès’ contribution was profoundly significant both in that it recognized childhood as a social construction rather than as a biological given, and in that it founded the history of childhood as a serious field of study. At the same time, his account of childhood has by now been widely criticized.

Ariès is likewise remembered for his invention of another field of study: the history of attitudes to death and dying. Ariès saw death, like childhood, as a social construction. His seminal work in this ambit is L'Homme devant la mort (1977), his last major book, published in the same year when his status as a historian was finally recognized by his induction into the École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS) as a directeur d'études.

There has been widespread criticism of the methods that Ariès used to draw his conclusions about the role of childhood in early modern Europe. One of his most noted critics was the historian Geoffrey Elton. Elton's main criticism of Ariès is paraphrased in Richard J. Evans's book on historiography, In Defence of History: "in everyday life children were indeed dressed differently to adults; they were just put in adult clothes to have their portraits painted".

That is to say that Ariès took early modern portraits as an accurate representation of the look of early modern families whereas a lot of the clients would use them to improve their status.

The assertion that the medieval world was ignorant of childhood has undergone considerable attack from other writers (for example, Kroll 1977, Shahar 1990).

Further criticism of Ariès is found in an article, available online, from 1992 by Harry Hendrick for the Journal of the Economic History Society. Within the article, entitled Children and Childhood, Hendrick lists four criticisms of Ariès's work.

"Firstly that his data are either unrepresentative or unreliable. Secondly that he takes evidence out of context, confuses prescription with practice, and uses atypical examples. Thirdly, that he implicitly denies the immutability of the special needs of children, for food, clothing, shelter, affection and conversation. Fourthly, that he puts undue emphasis on the work of moralists and educationalists while saying little of economic and political factors"

Roger Chartier, born on December 9, 1945 in Lyon, is a French historian and historiographer who was part of the Annales school. He worked on the history of books, publishing and reading.

Originally from Lyon, he studied at the Ampère lycée (high school). Between 1964 and 1969, he was a student at the École normale supérieure de Saint - Cloud and, at the same time, he pursued a 3 year degree (French licence) followed by a master's degree at the Sorbonne (1966 – 1967). In 1969, he succeeded at his agrégation in history.

He taught as an associate professor at the Lycée Louis - le - Grand in Paris between 1969 and 1970. In the same year, he became assistant in Modern History at the University of Paris I, then senior lecturer at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (EHESS). He became a lecturer (from 1978 – 1983) and then director of studies at the EHESS until 2006. In 2006 he was appointed professor at the Collège de France, holder of the "Written Culture in Modern Europe" chair. He also hosted the show Les lundis de l'histoire on France Culture, in which he talked with historians who publish books on modern history (16th – 18th centuries).

The works of Roger Chartier are described by Dorothea Kraus as follows: "Authors, texts, books, and readers are four poles linked by Roger Chartier's work on the history of written culture; poles between which he attempts to draw connections through a cultural history of social life. The concept of 'appropriation' makes it possible for this perspective not only to give rise to these research topics, but also put them in touch with reading practices that determine appropriation, and which, in turn, depend on the reading skills of a community of readers, author strategies, and text formats."