<Back to Index>

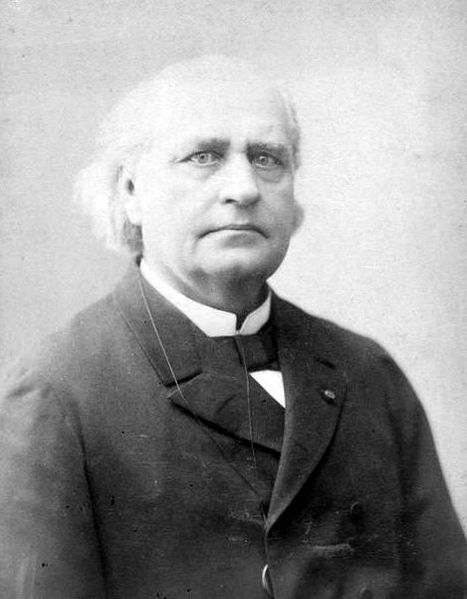

- Poet Charles Marie René Leconte de Lisle, 1818

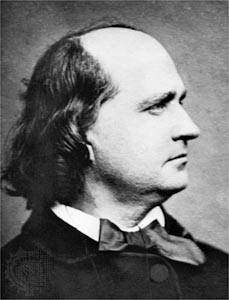

- Poet Théodore Faullain de Banville, 1823

PAGE SPONSOR

Charles Marie René Leconte de Lisle (22 October 1818 – 17 July 1894) was a French poet of the Parnassian movement.

Leconte de Lisle was born on the island of Réunion. His father, an army surgeon, who brought him up with great severity, sent him to travel in the East Indies with a view to preparing him for a commercial life. After this voyage he went to Rennes to complete his education, studying especially Greek, Italian and history. He returned once or twice to Réunion, but in 1846 settled definitely in Paris. His first volume, La Venus de Milo, attracted to him a number of friends many of whom were passionately devoted to classical literature. In 1873 he was made assistant librarian at the Luxembourg Palace; in 1886 he was elected to the Académie française in succession to Victor Hugo. His Poèmes antiques appeared in 1852; Poèmes et poésies in 1854; Le Chemin de la croix in 1859; the Poèmes barbares, in their first form, in 1862; Les Érinnyes, a tragedy after the Greek model, in 1872; for which incidental music was provided by Jules Massenet (which included the "Invocation" for cello and orchestra, an arrangement of his famous "Élégie"); the Poèmes tragiques in 1884; L'Apollonide, another classical tragedy, in 1888; and two posthumous volumes, Derniers poèmes in 1899, and Premières poésies et lettres intimes in 1902. In addition to his original work in verse, he published a series of admirable prose translations of Theocritus, Homer, Hesiod, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Horace. He died at Voisins, near Louveciennes, in the department Yvelines.

In Leconte de Lisle the Parnassian movement seems to crystallize. His verse is clear, sonorous, dignified, deliberate in movement, classically correct in rhythm, full of exotic local color, of savage names, of realistic rhetoric. It has its own kind of romance, in its "legend of the ages," so different from Hugo's, so much fuller of scholarship and the historic sense, yet with far less of human pity. Coldness cultivated as a kind of artistic distinction seems to turn all his poetry to marble, in spite of the fire at its heart. Most of Leconte de Lisle's poems are little chill epics, in which legend is fossilized. They have the lofty monotony of a single conception of life and of the universe. He sees the world as what Byron called it, "a glorious blunder", and desires only to stand a little apart from the throng, meditating scornfully. Hope, with him, becomes no more than this desperate certainty:

Tu te tairas, ô voix sinistre des vivants!

You will be quiet, o sinister voice of the living!

His only prayer is to Death, "divine Death", that it may gather its children to its breast:

Affranchis - nous du temps, du nombre et de l'espace, Et rends - nous le repos que la vie a troublé!

Free us of time, of name and of space / and give us the repose which life hath troubled!

The interval which is his he accepts with something of the defiance of his own Cain, refusing to fill it with the triviality of happiness, waiting even upon beauty with a certain inflexible austerity. He listens and watches, throughout the world, for echoes and glimpses of great tragic passions, languid with fire in the East, a tumultuous conflagration in the Middle Ages, a somber darkness in the heroic ages of the North. The burning emptiness of the desert attracts him, the inexplicable melancholy of the dogs that bark at the moon; he would interpret the jaguar's dreams, the sleep of the condor. He sees nature with the same wrathful impatience as man, praising it for its destructive energies, its haste to crush out human life before the stars fall into chaos, and the world with them, as one of the least of stars. He sings the "Dies Irae" exultingly; only seeming to desire an end of God as well as of man, universal nothingness. He conceives that he does well to be angry, and this anger is indeed the personal note of his pessimism; but it leaves him somewhat apart from the philosophical poets, too fierce for wisdom and not rapturous enough for poetry.

Théodore Faullain de Banville (14 March 1823 – 13 March 1891) was a French poet and writer.

Banville was born in Moulins in Allier, Auvergne, the son of a captain in the French navy. His boyhood, by his own account, was cheerlessly passed at a lycée in Paris; he was not harshly treated, but took no part in the amusements of his companions. On leaving school with but slender means of support, he devoted himself to letters, and in 1842 published his first volume of verse (Les Cariatides), which was followed by Les Stalactites in 1846. The poems encountered some adverse criticism, but secured for their author the approbation and friendship of Alfred de Vigny and Jules Janin.

From then on, Banville's life was steadily devoted to literary production and criticism. He printed other volumes of verse, among which the Odes funambulesques (1857) received unstinted praise from Victor Hugo, to whom they were dedicated. Later, several comedies in verse were produced at the Théâtre Français and on other stages; and from 1853 onward a stream of prose flowed from his industrious pen, including studies of Parisian manners, sketches of well known persons, and a series of tales, most of which were republished in his collected works (1875 – 1878). He also wrote freely for reviews, and acted as dramatic critic for more than one newspaper. Throughout a life spent mainly in Paris, Banville's genial character and cultivated mind won him the friendship of the chief men of letters of his time.

In 1858 he was decorated with the Legion of Honor, and was promoted to be an officer of the order in 1886. He died in Paris in 1891 at the age of 68, and was buried in Montparnasse Cemetery.

There is a street named after him in the 17th Arrondissement in Paris.