<Back to Index>

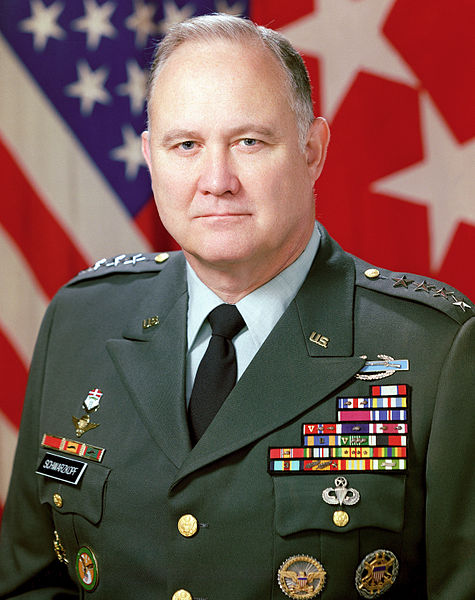

- Commander of U.S. Central Command General Herbert Norman Schwarzkopf, 1934

PAGE SPONSOR

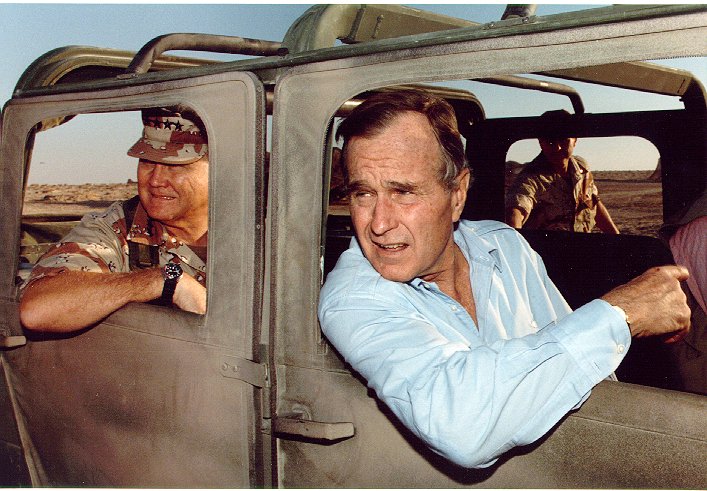

General Herbert Norman Schwarzkopf (born August 22, 1934 - December 27, 2012), also known as "Stormin' Norman" and "The Bear", was a United States Army general who, while he served as Commander of U.S. Central Command, was commander of the Coalition Forces in the Gulf War of 1991.

Schwarzkopf was born in Trenton, New Jersey, the son of Ruth Alice (née Bowman) and Herbert Norman Schwarzkopf. His father served in the US Army before becoming the Superintendent of the New Jersey State Police, where he worked as a lead investigator on the infamous Lindbergh kidnapping before returning to an Army career and rising to the rank of Major General. In January 1952, Schwarzkopf's birth certificate was amended to make his name "H. Norman Schwarzkopf". This was done as an act of revenge against the upper class cadets at West Point because his father hated his own first name "Herbert" and when he attended West Point the upper class cadets yelled at him for signing his name "H. Norman Schwarzkopf". His connection with the Persian Gulf region began very early. In 1946, when he was 12, he and the rest of his family joined their father, stationed in Tehran, Iran, where his father went on to be instrumental in Operation Ajax, eventually forming the Shah's secret police SAVAK, as well. He attended the Community High School in Tehran, later the International School of Geneva at La Châtaigneraie, Frankfurt High School in Frankfurt, Germany, and attended and graduated from Valley Forge Military Academy. He was also a member of Mensa.

After attending Valley Forge Military Academy, Schwarzkopf, an army brat, attended the United States Military Academy, where he graduated 43rd in his class in 1956 with a Bachelor of Science degree. He also attended the University of Southern California, where he received a Master of Science in mechanical engineering in 1964. His special field of study was guided missile engineering, a program that USC developed with the Army, which incorporated both aeronautical and mechanical training. He later attended the U.S. Army War College as well.

Upon graduating from West Point he was commissioned a Second Lieutenant. He received advanced infantry and airborne training at Fort Benning, Georgia. He was a platoon leader and served as executive officer of the 2nd Airborne Battle Group, 187th Airborne Infantry Regiment at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. Next he was aide - de - camp to the Berlin Brigade in 1960 and 1961, a crucial time in the history of that divided city (the Berlin Wall was erected by East German and Soviet forces only a week after he left). In 1965, after completing his masters degree at USC, Schwarzkopf served at West Point as an instructor in the mechanical engineering department.

More and more of his former classmates were heading to Vietnam as advisers to the South Vietnamese army and, in 1965, following Schwarzkopf's first year as a member of the faculty at West Point, he applied to join them. Schwarzkopf served as a task force adviser to the South Vietnamese Airborne Division; during that time he was promoted from Captain to Major. When his tour of duty in Vietnam was over, he returned to serve out the remaining two years of his obligated teaching service at West Point. In 1968, Major Schwarzkopf became a Lieutenant Colonel. In this same year, he married Brenda Holsinger.

In Vietnam in March 1970, Schwarzkopf was involved in rescuing men of his battalion from a minefield. He had received word that men under his command had encountered a minefield on the notorious Batangan Peninsula, he rushed to the scene in his helicopter, as was his custom while a battalion commander, in order to make his helicopter available. He found several soldiers still trapped in the minefield. Schwarzkopf urged them to retrace their steps slowly. Still, one man tripped a mine and was severely wounded but remained conscious. As the wounded man flailed in agony, the soldiers around him feared that he would set off another mine. Schwarzkopf, also wounded by the explosion, crawled across the minefield to the wounded man and held him down (using a "pinning" technique from his wrestling days at West Point) so another could splint his shattered leg. One soldier stepped away to break a branch from a nearby tree to make the splint. In doing so, he too hit a mine, which killed him and the two men closest to him, and blew an arm and a leg off Schwarzkopf's artillery liaison officer. Eventually, Schwarzkopf led his surviving men to safety, by ordering the division engineers to mark the locations of the mines with shaving cream. (Some of the mines were of French manufacture and dated back to the Indochina conflict of the 1950s; others were brought by Japanese forces in World War II). Schwarzkopf says in his autobiography It Doesn't Take a Hero that this incident firmly cemented his reputation as an officer who would risk his life for the soldiers under his command.

Schwarzkopf told his men that they might not like some of his strict rules, but it was for their own good. He told them "When you get on that plane to go home, if the last thing you think about me is 'I hate that son of a bitch', then that is fine because you're going home alive." Lt. General Hal Moore later wrote that it was during his time in Vietnam that Schwarzkopf acquired what later became his infamous temper, while arguing via radio for passing American Hueys to land and pick up his wounded men.

During the 1970s, Schwarzkopf's star continued to rise. He attended the U.S. Army War College at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania (delayed for a year so that he could undergo back surgery for a congenital back condition that was aggravated by his combat services), served on the Army General Staff at The Pentagon, was deputy commander of U.S. Forces Alaska under Brigadier General Willard Latham, and served as commander of the 1st Brigade of the 9th Infantry Division at Fort Lewis, Washington. After promotion to Brigadier General, he was assigned as Plans & Policy Officer (Assistant J3) at U.S. Pacific Command for two years. He then served as Assistant Division Commander (Support) of the 8th Mechanized Division and as Community Commander of Mainz, West Germany, during which the city was visited by Pope John Paul II, thus putting Schwarzkopf in charge of the U.S. security forces during the pontiff's visit. He was promoted to Major General, and given command of the 24th Mechanized Infantry Division, at Fort Stewart, Georgia. A year into this assignment, a coup had taken place on the tiny Caribbean island of Grenada. With Cuban assistance, the Grenadian revolutionaries were building an airfield which U.S. intelligence suspected would be used to supply insurgents in Central America. It was also feared that Americans studying on the island might be taken hostage. Since an amphibious landing was called for, the entire operation was placed under the command of an admiral. Schwarzkopf was sent by the Army as an advisor to the Navy to make sure the Army units attached to the task force were used correctly. He quickly won the confidence of his superior and was named Deputy Commander of the Joint Task Force. While the Grenada operation proved more difficult than its planners had anticipated, the coup was quickly thwarted. Order was restored, elections were scheduled, and the American students returned home unharmed. In 1985, Schwarzkopf returned to the Pentagon to serve as an assistant to Lieutenant General Carl Vuono (who was then Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations). In 1986, Schwarzkopf was promoted to Lieutenant General, and was appointed as Commanding General of I Corps at Ft. Lewis. After only serving one year in command, he was called back to Washington to serve as Vuono's assistant (Vuono himself was promoted to General of the Army's Training and Doctrine Command, only later to become Army Chief of Staff), this time in operations Deputy Chief position.

In 1988, he was promoted to General and was appointed Commander - in - Chief of the U.S. Central Command. The U.S. Central Command, based at MacDill Air Force Base, in Tampa, Florida, was responsible at the time for operations in the Horn of Africa, the Middle East and South Asia. In his capacity as commander, Schwarzkopf prepared a detailed plan for the defense of the oil fields of the Persian Gulf against a hypothetical invasion by Iraq, among other plans.

The Iraq plan served as the basis of the war game of 1990. Within the same month, Iraq invaded Kuwait, and Schwarzkopf's plan had an immediate practical application, which was as the basis for Operation Desert Shield, the defense of Saudi Arabia. As overall commander, Schwarzkopf initially was concerned that operational forces in the theater were inadequately supplied and equipped for large scale combat in a desert environment. During preparations for Desert Storm, as the result of initiatives by General Schwarzkopf, the Desert camouflage combat uniform was produced in 100% cotton poplin without reinforcement panels in order to improve comfort for U.S. troops operating in the hot, dry desert conditions. A total of 500,000 improved cotton BDUs were ordered. However, cost concerns caused the cotton six color Desert BDU to be discontinued shortly after the Gulf War. A few months later, General Schwarzkopf's offensive operational plan, called Operation Desert Storm (co-authored with his deputy commander, Lieutenant General Cal Waller and others on his staff), was the "left hook" strategy that went into Iraq behind the Iraqi forces occupying Kuwait and was widely credited with bringing the ground war to a close in just four days. He was personally very visible in the conduct of the war, giving frequent press conferences, and was dubbed "Stormin' Norman."

After the war, Schwarzkopf was offered the position of Chief of Staff of the United States Army by Secretary of the Army Michael P.W. Stone, but he declined. He retired from active service in August 1991, and shortly thereafter wrote an autobiography, It Doesn't Take a Hero, published in 1992. There was some speculation in the aftermath of the Gulf War that he might run for political office, but he did not do so. In retirement, Schwarzkopf served as a military analyst for NBC, most recently for Operation Iraqi Freedom, along with promoting prostate cancer awareness, a disease with which he was diagnosed in 1993, and for which he was successfully treated. Later, Schwarzkopf donated most of his time to multiple charities and community activities. He sat on the board of Remington, and several other high profile corporations. On May 4, 2008 Schwarzkopf was inducted into New Jersey's Hall of Fame. He was also an honorary board member of the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation. Schwarzkopf lived in Tampa.

Schwarzkopf supported President George W. Bush in his successful 2004 re-election bid against Democratic nominee John Kerry,

stating "(President Bush) is the candidate who has demonstrated the

conviction needed to defeat terrorism. In contrast to the President's

steadfast determination to defeat our enemies, Senator Kerry has a

record of weakness that gives me no confidence in his ability to fight

and win the War on Terror."

However, by December 2004, Schwarzkopf became critical of the Iraq War

and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld. Schwarzkopf endorsed Republican nominee John McCain in the 2008 presidential election.

Schwarzkopf died at age 78 on December 27, 2012, of complications following a bout of pneumonia. A memorial service was conducted on February 28, 2013, at the Cadet Chapel at West Point, which was attended by Colin Powell, Schwarzkopf's family, and others. Schwarzkopf was cremated and his ashes were buried near those of his father in the West Point Cemetery in a ceremony attended by cadets, military leaders, New York and New Jersey State Police Troopers.

Among reactions to Schwarzkopf's death, George H. W. Bush said of

him: "General Norm Schwarzkopf, to me, epitomized the 'duty, service,

country' creed that has defended our freedom and seen this great Nation

through our most trying international crises. More than that, he was a

good and decent man and a dear friend."[126] In a statement, President Barack Obama

said "From his decorated service in Vietnam to the historic liberation

of Kuwait and his leadership of United States Central Command, General

Schwarzkopf stood tall for the country and Army he loved." In a letter, Secretary of the Army John McHugh and Army Chief of Staff General Raymond T. Odierno

wrote in a joint statement, "Our nation owes a great debt of gratitude

to General Schwarzkopf and our Soldiers will hold a special place in

their hearts for this great leader. While much will be written in coming

days of his many accomplishments, his most lasting and important

legacies are the tremendous soldiers he trained and led."

During his tour of duty in Vietnam, Schwarzkopf developed a reputation as a commander who preferred to lead from the front, even willing to risk his own life for his subordinates. His leadership style stressed preparedness, discipline and rigorous training, but also allowed his troops to enjoy the luxuries they had. His rehabilitation of the 1st Battalion, 6th Infantry stressed survival as well as offense. Like German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel and General George S. Patton, Schwarzkopf highly regarded decisiveness and valued determination among his commanders. He pushed for offensive combat over defensive operations in the Gulf War.

He was known to be extremely critical of staff officers

who were unprepared, but was even more contentious with other generals

who he felt were not aggressive enough. His frequent short temper with

subordinates was well known in his command. His leadership style was sometimes criticized by subordinates who felt it reduced their ability to solve problems creatively. Army Chief of Staff Carl E. Vuono,

a lifelong friend of Schwarzkopf, described him as "competent,

compassionate, egotistical, loyal, opinionated, funny, emotional,

sensitive to any slight. At times he can be an overbearing bastard, but

not with me."

While Colin Powell would say Schwarzkopf's strengths outweighed his

weaknesses, Dick Cheney personally disliked what he considered

Schwarzkopf's pretentious behavior with subordinates. Cheney doubted

Schwarzkopf's ability to lead the Gulf War, and so Powell dealt with

Schwarzkopf instead.

The quick and decisive results of the Gulf War were attributed to Schwarzkopf's leadership. Historian Rick Atkinson considered Schwarzkopf "the most theatrical American in uniform since Douglas MacArthur." Atkinson further contended that in his leadership during the Gulf War, Schwarzkopf conducted one of the greatest military campaigns of all time, providing the United States with its "first battlefield hero in decades." The later accomplishments of General Tommy Franks during Operation Enduring Freedom were compared favorably with those of Schwarzkopf. However, in an analysis of the effects of the Gulf War, several historians, including Spencer C. Tucker, contended that Schwarzkopf's ceasefire agreement allowed Iraq to continue to fly armed helicopters, which allowed it to later conduct operations against its Shia Arab and Kurdish populations. Schwarzkopf later wrote it would have been a mistake to continue the offensive and capture all of Iraq, noting that the U.S. would likely have had to pay the entire cost of rebuilding the country.

In a 2012 book, historian Thomas E. Ricks wrote Schwarzkopf's lack of experience with politics was disadvantageous to his conduct of the war. Ricks said that Schwarzkopf was overly cautious in the execution of his plans because of his fear of repeating mistakes in Vietnam, which meant his troops failed to destroy the Iraqi Republican Guard. Ricks further criticized Schwarzkopf for failing to relieve General Frederick M. Franks Jr. as well as other subordinates who Schwarzkopf said, in his memoirs, were ineffective. Ricks concluded that the Gulf War was a "tactical triumph but a strategic draw at best." In his memoirs, Schwarzkopf responded to these kinds of criticisms by saying his mandate had only been to liberate and safeguard Kuwait and that an invasion of Iraq would have been highly controversial, particularly among Middle Eastern military allies.

Schwarzkopf sought to change the relationship between journalists and the military, feeling that the news media's negative portrayal of the Vietnam War had degraded troops there. When he took command during the Gulf War, he sought an entirely different strategy, which was ultimately successful by favoring greater media coverage but subject to strict controls on the battlefield. Schwarzkopf favored the intense press surrounding the Gulf War conflict, feeling that blocking the news media, as had been done in Grenada, would contribute to affect public perception of the war in the United States negatively. His dealings with the press were thus frequent and very personal, and he conducted regular briefings for journalists. He would usually not attack media coverage, even if negative, unless he felt it was blatantly incorrect. He staged visible media appearances that played to patriotism.

In fact, Schwarzkopf believed extensive press coverage would help

build public support for the war and raise morale. In some press

conferences, he showed and explained advanced war-fighting technology

that the U.S. possessed to impress the public. These also had the side

effect of distracting the public from focusing on U.S. casualty counts

or the destruction wrought in the war.

Schwarzkopf's strategy was to control the message being sent and so he

ordered media on the battlefield to be escorted at all times. However,

several high profile reports publicized the CENTCOM strategy.

After the war, Schwarzkopf was very critical of military analysts who

scrutinized his operation, felt that some of them were poorly informed

on the factors involved in his planning, and felt that others were

violating operations security by revealing too much about how he might

plan the operation.

Schwarzkopf was a cousin of actress Marianna Hill. He was married in 1968 and had three children.

Madonna paid a special tribute to General Schwarzkopf during the 1990 Oscars ceremony on March 25, 1991 at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles California. When she performed the Academy Award winning song Sooner Or Later (I Always Get My Man) from the film Dick Tracy written by Stephen Sondheim she added the line “Talk to me General Schwarzkopf, tell me all about it.” Her performance was homage to Marilyn Monroe and saluting the general was reminiscent of the 1950s when Monroe paid her respects to General Dwight D. Eisenhower.