<Back to Index>

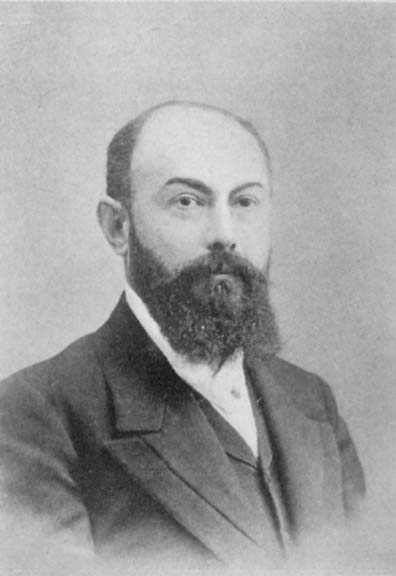

- Psychologist and Philosopher Pierre Marie Félix Janet, 1859

PAGE SPONSOR

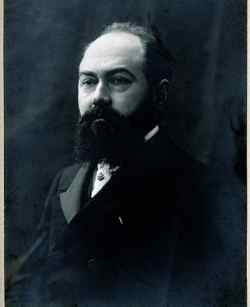

Pierre Marie Félix Janet (30 May 1859 – 24 February 1947) was a pioneering French psychologist, philosopher and psychotherapist in the field of dissociation and traumatic memory.

He is ranked alongside William James and Wilhelm Wundt as one of the founding fathers of psychology.

Janet studied under Jean - Martin Charcot at the Psychological Laboratory in Pitié - Salpêtrière Hospital, in Paris. He first published the results of his research in his philosophy thesis in 1889 and in his medical thesis, L'état mental des hystériques, in 1892. He earned a degree in medicine the following year in 1893.

In 1898, Janet was appointed lecturer in psychology at the Sorbonne, and in 1902 he attained the chair of experimental and comparative psychology at the Collège de France, a position he held until 1936. He was a member of the Institut de France from 1913, and a central figure in French psychology in the first half of the 20th century.

Janet was one of the first people to draw a connection between events in the subject's past life and his or her present day trauma, and coined the words ‘dissociation’ and ‘subconscious’. His study of the 'magnetic passion' or 'rapport' between the patient and the hypnotist anticipated later accounts of transference.

The twentieth century saw Janet developing a grand model of the mind in terms of levels of energy, efficiency and social competence, which he set out in publications from Obsessions and Pssychasthenia (1903) to From Anguish to Ecstasy (1926), and beyond. In its concern for the construction of the personality in social terms, it has been compared to the social behaviorism of George Herbert Mead something which explains Lacan's early praise of "Janet, who demonstrated so admirably the signification of feelings of persecution as phenomenological moments in social behavior".

Janet established a developmental model of the mind in terms of a hierarchy of nine 'tendencies' of increasingly complex organizational levels.

He detailed four Lower Tendencies, risimg from the Reflexive to the Elementary Intellectual; two Middle Tendencies, involving language and a social world; and three Higher Tendencies, the Rational - Ergotic world of work, and the Experimental and Progressive Tendencies.

Neurosis could be seen as a failure to integrate, or a regression to earlier tendencies; while Janet defined subconsciousness as "an act which has kept an inferior form amidst acts of a higher level".

Controversy over questions of priority between Janet and Freud emerged at the 1913 Congress of Medicine in London. Prior to that date Freud had freely acknowledged his debt to Janet, particularly in his work with Josef Breuer, writing for example of "the theory of hysterical phenomena first put forward by P. Janet and elaborated by Breuer and myself", and stating further that "we followed his example when we took the splitting of the mind and dissociation of the personality as the center of our position" - although he was also careful to point out where "the difference lies between our view and Janet's".

Again, writing of the neurotic's withdrawal from reality in 1911, Freud states: "Nor could a fact like this escape the observation of Pierre Janet; he spoke of a loss of 'the function of reality'". As late as 1930, he drew on Janet's expression 'psychological poverty' in his work on civilization.

In his report on psychoanalysis of 1913, however, Janet argued that many of the 'novel' terms of psychoanalysis were only old concepts renamed, even to the way his own 'psychological analysis' preceded Freud's 'psychoanalysis'. This provoked angry attacks from Freud's followers, and thereafter Freud's own attitude towards Janet cooled. In his lectures of 1915 - 16, he said that "for a long time I was prepared to give Janet very great credit for throwing light on neurotic symptoms, because he regarded them as expressions of idées inconscientes which dominated the patients, but, after what Freud saw as his backpedalling of 1913, "I think he has unnecessarily forfeited much credit".

The charge of plagiarism stung Freud especially. In his autobiographical sketch of 1925 he denied firmly that he had plagiarized from Janet, and as late as 1937 he refused to meet him on the grounds that "when the libel was spread by French writers that I had listened to his lectures and stolen his ideas he could with a word have put an end to such talk" but didn't.

A balanced judgement might be that Janet's ideas, as published, did indeed form (part of) Freud's starting point, but that he subsequently developed them substantively in his own fashion.

Carl Jung studied with Janet in Paris in 1902, and was much influenced by him, for example equating what he called a complex with Janet's idée fixe subconsciente.

Jung's view of the mind as "consisting of an indefinite, because unknown, number of complexes or fragmentary personalities" built upon what Janet in Psychological Automatism called 'simultaneous psychological existences'.

Jung wrote of the debt owed to "Janet for a deeper and more exact knowledge of hysterical symptoms", and talked of "the achievements of Janet, Flournoy, Freud and others" in exploring the unconscious.

Alfred Adler openly derived his inferiority complex from Janet's Sentiment d'incomplétude; and the two men cited each other's work on the issue in their writings.

In 1923, he wrote a definitive text, La médecine psychologique, on suggestion and in 1928 - 32, he published several definitive papers on memory.

While he did not publish much in English, the fifteen lectures he gave to the Harvard Medical School between 15 October and the end of November 1906 were published in 1907 as The Major Symptoms of Hysteria and he received an honorary doctorate from Harvard in 1936.

Of his great synthesis of human psychology, Henri Ellenberger wrote that "this requires about twenty books and several dozen of articles".