<Back to Index>

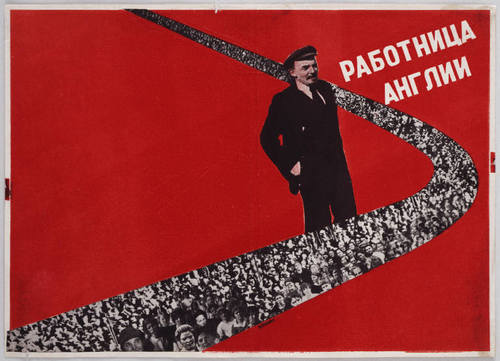

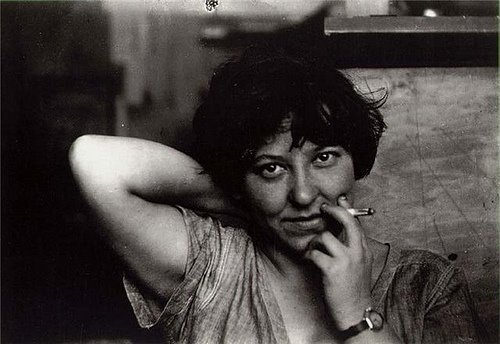

- Designer Varvara Fyodorovna Stepanova, 1894

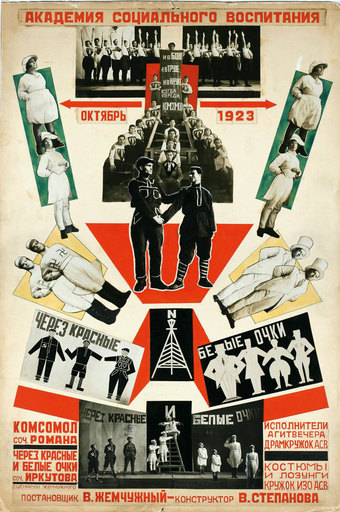

- Photographer Gustav Klutsis, 1895

PAGE SPONSOR

Varvara Fyodorovna Stepanova (Russian: Варва́ра Фёдоровна Степа́нова; 4 November [O.S. 23 October] 1894 - May 20, 1958) was a Russian artist. With her husband Alexander Rodchenko, she was associated with the Constructivist branch of the Russian avant garde, which rejected aesthetic values in favor of revolutionary ones. Her activities extended into propaganda, poetry, stage scenery and textile designs.

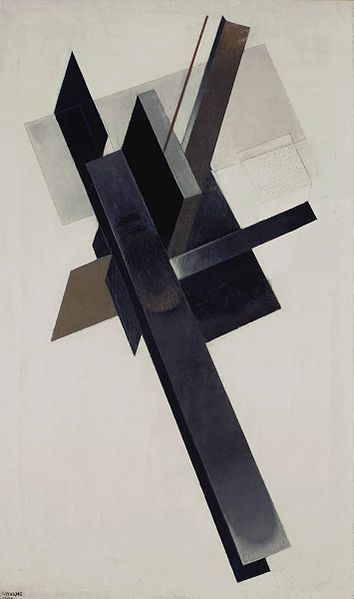

Varvara Stepanova who was born in Kaunas (in modern-day Lithuania) came from peasant origins but was able to get an education at Kazan Art School, Kazan. There she met her later husband and collaborator Alexander Rodchenko. In the years before the Russian Revolution of 1917 they leased an apartment in Moscow, owned by Wassily Kandinsky. These artists became some of the main figures in the Russian avant garde. The new abstract art in Russia which began around 1915 was a culmination of influences from Cubism, Italian Futurism and traditional peasant art. She designed Cubo-Futurist work for several artists' books, and studied under Jean Metzinger at Académie de La Palette, an art academy where the painters André Dunoyer de Segonzac and Henri Le Fauconnier also taught.

In the years following the revolution, Stepanova involved herself in poetry, philosophy, painting, graphic art, stage scenery construction, and textile and clothing designs. She contributed work to the Fifth State Exhibition and the Tenth State Exhibition, both in 1919.

In 1920 it came to a division between painters like Kasimir Malevich who continued to paint with the idea that art was a spiritual activity, and those who believed that they must work directly for the revolutionary development of the society. In 1921, together with Aleksei Gan, Rodchenko and Stepanova formed the first Working Group of Constructivists, which rejected fine art in favor of graphic design, photography, posters, and political propaganda. Also in 1921, Stepanova declared in her text for the exhibition 5x5=25, held in Moscow:

Composition is the contemplative approach of the artist. Technique and Industry have confronted art with the problem of construction as an active process and not reflective. The 'sanctity' of a work as a single entity is destroyed. The museum which was the treasury of art is now transformed into an archive.

The term 'Constructivist' was by then being used by the artists themselves to describe the direction their work was taking. The theater was another area where artists were able to communicate new artistic and social ideas. Stepanova designed the sets for The Death of Tarelkin in 1922.

In 1921, Stepanova moved almost exclusively into the realm of production, in which she felt her designs could achieve their broadest impact in aiding the development of the Soviet society. Russian Constructivist clothing represented the destabilization of the oppressive, elite aesthetics of the past and, instead, reflected utilitarian functionality and production. Gender and class distinctions gave way to functional, geometric clothing. In line with this objective, Stepanova sought to free the body in her designs, emphasizing clothing's functional rather than decorative qualities. Stepanova deeply believed clothing must be looked at in action. Unlike the aristocratic clothing that she felt sacrificed physical freedom for aesthetics, Stepanova dedicated herself to designing clothing for particular fields and occupational settings in such a way that the object's construction evinced its function. In addition, she sought to develop expedient means of clothing production through simple designs and strategic, economic use of fabrics.

Stepanova, thus, identified clothing as occupying two groups: prodezodezhda and sportodezhda. Within these categories, she attended to logical, efficient production and construction of the garments. However, war-induced poverty placed economic restrictions on the

Russian Constructivists’ industrial fervor, and their direct engagement

with production was never fully realized. Thus, most of her designs were

not mass produced and circulated.

The first, prodezodezhda, or production/working clothing in basic styles, included theater costumes as well as professional and industrial garments. In the early 1920s, Stepanova entered the clothing industry through her costume designs in theater, in which she translated her artistic affinity for geometric shapes into functional, emblematic clothing. Made of dark blue and grey material, the graphic costumes allowed actors to maximize the appearance of their movements, exaggerating them for the stage and transforming the body into a dynamic composition of geometric shapes and lines.

Within this category, Stepanova began designing spetsodezhda, or clothing specialized for a specific occupation. In doing so, she designed clothing for men and women in both industrial and professional capacities with meticulous consideration of seaming, pockets, and buttons to ensure each aspect of the costume maintained a functional intention. Regardless of the occupational context, her working clothing carried a distinctive geometric and linear edge, rendering the body into a graphic composition and boxy, androgynous form.

The second category, sportodezhda, or sports costumes, also presented bold lines, large forms, and contrasting colors to enable and emphasize the body's movements and allow spectators to easily distinguish one team from the other. Stepanova even rendered the team's emblem into a graphic design. The sports arena offered a context for Stepanova to realize an idealized bodily neutralization, and her uniforms were often unisex with pants and a belted tunic that obscured the human form.

Stepanova carried out her ideal of engaging with industrial production in the following year when she, with Lyubov Popova, became designer of textiles at the Tsindel (the First State Textile Factory) near Moscow, and in 1924 became professor of textile design at the Vkhutemas (Higher Technical Artistic Studios). As a constructivist, Stepanova not only transposed bold graphic designs onto her fabrics, but also focused heavily on their production. Stepanova only worked a little over a year at The First Textile Printing Factory, but she designed more than 150 fabric designs in 1924. Although she was inspired to develop new types of fabric, the current technology restricted her to printed patterns on monotone surfaces. By her own artistic choice, she also limited her color palette to one or two dyes. Although she only used triangles, circles, squares, and lines, Stepanova superimposed these geometric forms onto one another to create a dynamic, multi-dimensional design.

Stepanova practiced typography, book design and contributed to the magazine LEF throughout the early 1920s. As part of a government campaign to promote universal literacy, Stepanova organized a "Book Evening" in 1924. This was a performance that featured characters from pre- and post-revolutionary literature battling each other.

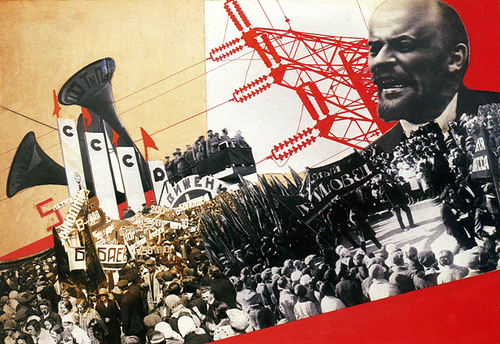

Gustav Gustavovich Klutsis (Latvian: Gustavs Klucis, Russian: Густав Густавович Клуцис; 4 January 1895 - 26 February 1938) was a pioneering Latvian photographer and major member of the Constructivist avant garde in the early 20th century. He is known for the Soviet revolutionary and Stalinist propaganda he produced with his wife Valentina Kulagina and for the development of photomontage techniques.

Born in Ķoņi parish, near Rūjiena, Klutsis began his artistic training in Riga in 1912. In 1915 he was drafted into the Russian Army, serving in a Latvian riflemen detachment, then went to Moscow in 1917. As a soldier of the 9th Latvian Riflemen Regiment, Klutsis served among Vladimir Lenin's personal guard in the Smolny in 1917 - 1918 and was later transferred to Moscow to serve as part of the guard of the Kremlin (1919 - 1924).

In 1918 - 1921 he began art studies under Kazimir Malevich and Antoine Pevsner, joined the Communist Party, met and married longtime collaborator Valentina Kulagina, and graduated from the state run art school VKhUTEMAS. He would continue to be associated with VKhUTEMAS as a professor of color theory from 1924 until the school closed in 1930.

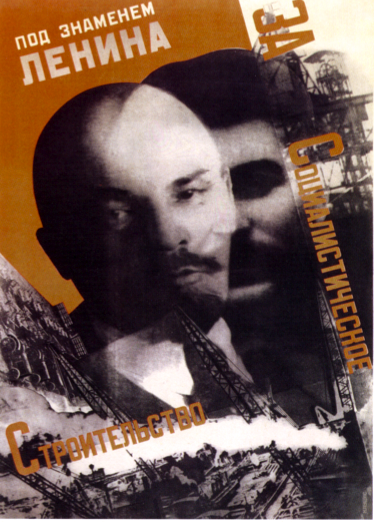

Klutsis taught, wrote, and produced political art for the Soviet state for the rest of his life. As the political background degraded through the 1920s and 1930s, Klutsis and Kulagina came under increasing pressure to limit their subject matter and techniques. Once joyful, revolutionary and utopian, by 1935 their art was devoted to furthering Joseph Stalin's cult of personality.

Despite his active and loyal service to the party, Klutsis was

arrested in Moscow on 16 January 1938, as a part of the so-called

"Latvian Operation" as he prepared to leave for the New York World's

Fair.

Kulagina agonized for months, then years, over his disappearance. His

sentence was passed by the NKVD Commission and the USSR Prosecutor’s

Office on 11 February 1938, and he was executed on 26 February 1938, at

the Butovo NKVD training ground near Moscow. He was rehabilitated on 25

August 1956 for lack of corpus delicti.

Klutsis worked in a variety of experimental media. He liked to use propaganda as a sign or revolutionary background image. His first project of note, in 1922, was a series of semi-portable multimedia agitprop kiosks to be installed on the streets of Moscow, integrating "radio-orators", film screens, and newsprint displays, all to celebrate the fifth anniversary of the Revolution. Like other Constructivists he worked in sculpture, produced exhibition installations, illustrations and ephemera.

But Klutsis and Kulagina are primarily known for their photomontages. The names of some of their best posters, such as "Electrification of the whole country" (1920), "There can be no revolutionary movement without a revolutionary theory" (1927), and "Field shock workers into the fight for the socialist reconstruction" (1932), belied the fresh, powerful, and sometimes eerie images. For economy they often posed for, and inserted themselves into, these images, disguised as shock workers or peasants. Their dynamic compositions, distortions of scale and space, angled viewpoints and colliding perspectives make them perpetually modern.

Klutsis is one of four artists with a claim to having invented the subgenre of political photo montage in 1918 (along with the German Dadaists Hannah Höch and Raoul Hausmann, and the Russian El Lissitzky). He worked alongside Lissitzky on the Pressa International exhibition in Cologne.